Dog Gone

Aarrrooooo… Aarrrooooo…

It’s 3am, late August, and I’m housesitting for friends when suddenly the dog is howling like he’s the one who spent the night shooting pool at the local saloon. “Oh please, please dog, give me a break,” I pray. But the mutt goes on howling until I climb out of bed, stumble downstairs, and out the front door.

“Casey, you fleabag from hell,” I shout before I recall that Casey is a Malamute the size of a wolf, that someone has poured peroxide over my brain, and that this is not my cabin but a prissy Bozeman subdivision pasted on the prairie.

The great lug of a dog lies there in the pale yellow pool of porch light, watching me with desolate eyes. I sink down beside him, scratch him behind his tattered ears.

“What’s the matter, old fella?” I inquire. For Casey’s muzzle is indeed gray, his teeth yellow and broken. Casey whimpers and swallows, heaves his head onto my lap. After a while the predawn chill gets to me, and I haul myself to my feet. I check his bowls, but there’s plenty of food and water.

“What is it, old boy? Want to come in?” I open the screen door and cluck in proper doggy fashion, but Casey isn’t having it. That’s not surprising, since he sports a coat like a musk ox and only ventures inside on the nastiest days. A moon like a smirk hangs in the summer sky while I assure myself that Casey just misses a good mauling by my friend’s two kids. Besides, I feel foolish out there in my boxers, talking to a dog. I trudge up the stairs, ease myself into the unfamiliar bed.

The room is filled with brain-piercing splinters of light, but it seems like I’ve just closed my eyes when—Aarrrooooo—Casey’s at it again. I pop four extra-strength pain relievers and gulp a can of Coke. I run cold water into the kitchen sink and dunk my head under. Only then do I step to the door.

Casey, his black and silver coat shimmering in the sun, is still sprawled among the kids’ toys on the front porch. He looks miserable, blinking rapidly, his tongue hanging out. I can’t convince him to move into the shade, and he turns his head away when I push his bowls under his nose.

I finally bite the bullet and call the vet, who happens to live in the green ranch house three doors down. The vet says he’ll be right over. After he finishes mowing the lawn. I spend the time with Casey’s head in my lap. Scratching him. Stroking him. Telling him tales of when dogs ruled the world. It’s surely the right thing to do, although I would like to maintain a little distance. After shepherding him through a gunshot, a serious stomach laceration, and a bloody beat-down by a Doberman pinscher, I lost Merlin, my German shorthair, not quite a year ago. I'm hesitant to get close to another dog.

Twenty minutes later, the vet roars up in his brand-new black Silverado. He may be a neighbor, but he’s not my neighbor. Which is to say that, bolstered by a rowdy ginger moustache, a cowboy hat, and a hank of snoose, he makes it clear that this is Sunday, his day off, that he’s doing me a very big favor and that he’d rather be working with cows.

After some prodding and poking, the vet declares that Casey has been eating out of garbage cans and needs a purge. “I don’t have any, um, enema gear,” I explain.

“Run into town and buy a couple of Fleet’s enemas.”

“But Casey is huge. What if he doesn’t want an enema?”

The vet spits and looks off at the Bridgers, patient with the balding dolt who cradles the panting dog. “Casey is sick and old. If he snaps you’ll probably have time to get out of his way.”

That probably resonates in my mind like a bowling ball in a 55-gallon drum.

Nevertheless, off to town I go and return with a pair of enemas, greenish radioactive-looking slush in industrial strength plastic bags. Casey, meanwhile, has disappeared. I circle the yellow split-level twice, discover him out back in the shade beneath the redwood deck. Way back under the deck where I’ll have to belly like a grunt. At first I’m put off by the close quarters and spider webs that cling to my face. Then I realize that it’s so tight there’s no way Casey can whirl and snap. I worm my way between the planks and cat-box smelling earth. Casey moans when I lift his tail and administer the first injection. Feeling like a brute, I lift his tail again, then worm my way from beneath the deck.

I check on Casey an hour later. Nothing. He lies there with his eyes closed, whimpering and twitching, biting off air in chunks. I feel crummy. Although I can whisper to him, there’s not much room to love him up.

Back inside, I fall asleep in the recliner. By the time I get back to Casey, the sun has climbed over the house and is scorching the deck. He’ll be coming out of there soon, I’m thinking as I snake my way in.

Not in this life. Casey, tiger-striped from the sun through the planks, is dead. After a moment’s confusion, I decide to leave him there because it’s mostly shady and it’s Sunday, the day his owners are supposed to call. Like a middle-aged child, I want someone to tell me what to do.

The temperature climbs to 87 degrees and Casey spends the afternoon roasting. His masters don’t call and I sleep badly, one ear cocked for the phone. The answering machine is still mute when I get back from work late the next afternoon, and a quick check reveals that Casey is wedged now beneath the deck, and has begun to stink and bloat. I find some scraps of clothesline in the garage and knot them together. I tie one end to Casey’s hind legs, the other to the bumper of my old pickup and haul him out. I grab a plank from the garage and drag Casey’s heavy, awkward body into the bed of the truck.

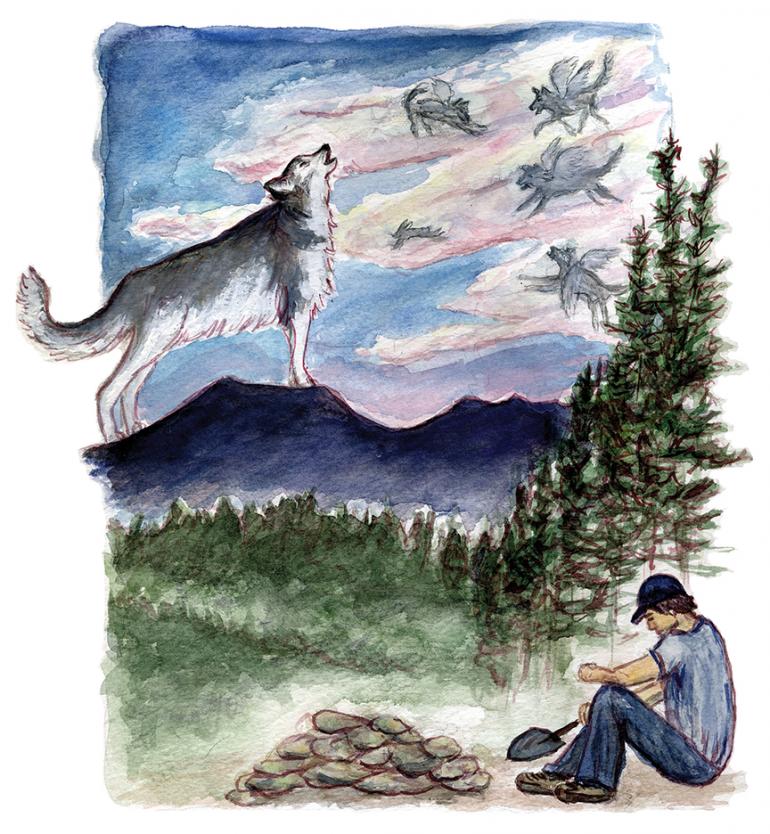

The sun is already slipping behind the Bridgers as I haul him up Olson Creek Road, where I dig a shallow grave back in the timber, bury him beneath a cairn of lichen-speckled rocks. The mountains are silhouettes by the time I finish and the shadows have come down with all the weight of night. I sit beside Casey’s grave with my head bowed and my fists tightly clenched. It seems like an ignominious end for an old guy who brought so much joy to a couple of little kids and blessed me with a few rare minutes of grace.

Climbing into my truck, I remember that we’ll all be old dogs someday, unceremoniously hauled out from under the porch of life and buried a few feet under. “Love ‘em while you got ‘em” comes to my mind as I drive down the canyon, and I wonder if I’m ready for another dog.