Unveiling the long, secretive history of climbing in the Beartooth Mountains.

Thirty miles as the crow flies from the Haufbrau—the beating heart of Bozeman’s climbing scene—lies the edge of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, a place where the climbing history has been indelibly shaped by a rowdy bunch of North America's most legendary alpinists.

The Beartooth Mountains are comprised of some of the oldest rock on Earth—crystalline granite and gneiss—that’s almost four billion years old. In the summer, daily thunderstorms are the norm, and mid-July snowfall is not unheard of. You’re more likely to encounter mountain goats, bighorn sheep, bears, moose, marmots, wolverines, and foxes than other humans in parts of the range. When temperatures drop and snow falls in winter, the Beartooth’s highest summits become as remote as the Alaska Range.

The history of climbing in these mountains is equally mysterious, shrouded in secrecy and lore. Unlike many of the country's great alpine climbing venues—where documentation of first ascents, guidebooks, and trip reports have long been extensively shared with the public—exploration in the Beartooths has always been tight-lipped and exclusive.

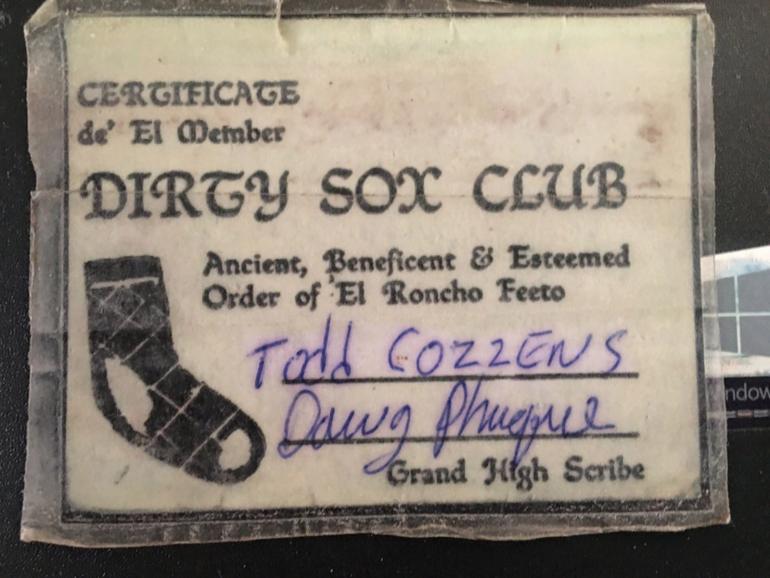

In 1971, four teenage climbers in Bozeman, were inspired by the lore of their predecessors and inaugurated the Dirty Sox Club.

The development of climbing in Montana was generally secluded from the rest of the country. Lacking destination venues like Yosemite and the Sierra Nevadas in California, the Wind Rivers and the Tetons in Wyoming, and the Cascades in Washington, many assumed that Montana simply didn’t have any worthwhile climbing. Over the decades, locals have been more than happy to maintain this facade.

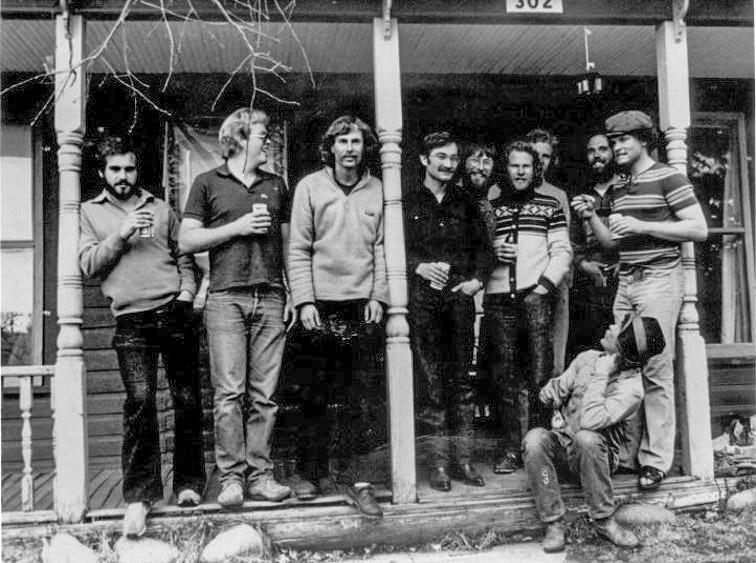

While the 47-day first ascent of the Nose on El Capitan in 1958 by Warren Harding, Wayne Merry, and George Whitmore established Yosemite as the epicenter of modern climbing technique, climbing in Montana was still in its infancy. In the 1960s, a band of young mountaineers who called themselves the “Wool Sox Club” began ticking off some of Montana’s earliest alpine climbs. Disaster struck in 1969 when an avalanche on Mount Cleveland in Glacier National Park killed five climbers, three of which were Wool Sox members. It shook the nascent climbing community to its core, tamed enthusiasm for local mountaineering, and caused the club to disassemble.

The local climbing scene at the time was small, but the club steadily grew as legends joined their ranks

In 1971, however, four teenage climbers in Bozeman—Brian Gary, Brian Leo, Dougal McCarty, and Dave Vaughan—were inspired by the lore of their predecessors and inaugurated the Dirty Sox Club. They quickly enlisted the freshly transplanted Pat Callis—a humble MSU professor-climber, most known for his first ascent of Mount Robson’s north face in British Columbia, as well as his climbs with pioneers such as Harding, Fred Beckey, and Layton Kor—as their first invited member. Under Callis’s tutelage, the club’s horizons expanded, and they began fervently ticking off first ascents across southwest Montana. But this young clique of climbers became equally—if not more—notorious for their debaucherous club “meetings” as they did for their climbing.

Often opening with well-intentioned, responsible activities like slideshow presentations, dinners, conversations about climbing, and sometimes climbing itself, meetings were prone to quickly degenerate into chaos. Skiing down indoor staircases and riding motorcycles up them, smoking hookah in the bathtub and drinking cases of pilfered champagne, a wild chase ending in the shooting and stabbing of an escaped pig, and receiving jail time for “disturbing the peace” at a rodeo in Dillon were all notable happenings during the assemblies of the burgeoning "Beneficent Order of El Roncho Feeto."

The club’s exclusivity waxed and waned depending on the available supply of beer. Occasionally, provisional membership was granted, and meetings consisted of “a few actual members and as many spontaneously recruited temporary members as were required to get enough money for a keg or two.”

The Mount Cleveland disaster shook the nascent climbing community to its core, tamed enthusiasm for local mountaineering, and caused the club to disassemble.

Permanent, lifelong membership was not easy to come by, though. Bill Dockins—a prolific local first ascensionist and guidebook author—laments his exclusion from the club for years. Jack Tackle—one of America’s most legendary alpinists and author of an extensive list of first ascents in the Himalaya and Alaska—was not accepted as a Dirty Sox member until after his first ascent on Mount Waddington in 1977. However, possessing “any deviance from normal psychology,” “a crummy credit history,” or "any sort of verifiable criminal history” could get any applicant “one big step closer to glorious membership.”

The local climbing scene at the time was small, but the club steadily grew as legends like Fred Beckey and Gray Thompson joined their ranks. Their appetites for first ascents were so voracious that many of the classic trad and alpine routes we enjoy today were established by Dirty Sox members.

However, the club’s exclusivity molded their approach to documentation and the sharing of information on their climbs. Placing emphasis on safeguarding their climbing goldmine from the rest of the world, members never shared reports with popular magazines or the Alpine Journal. A collection of the club’s topographic maps and route logs is rumored to have been kept by Jim Kanzler. Tragically, they were destroyed when his Red Lodge home burned.

The young clique of climbers became equally—if not more—notorious for their debaucherous club “meetings” as they did for their climbing.

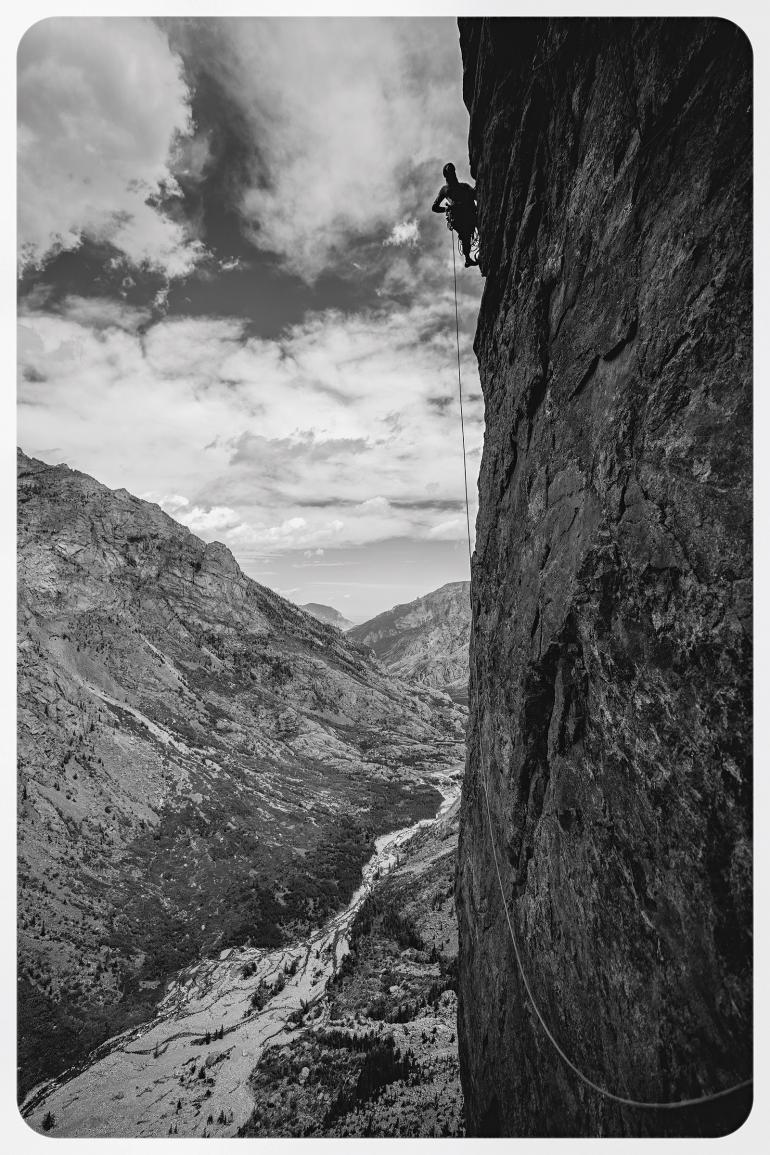

The Dirty Sox Club’s motivations for secrecy weren’t all selfish. The Beartooths were one of the last truly wild, undocumented alpine-climbing destinations in the Lower 48, and it was out of a special love and reverence for the place that members tried to keep it that way. The Beartooths didn’t boast the perfect rock of the Sierras or the Wind Rivers, but they provided a seemingly limitless supply of exemplary, untouched climbing close to home for alpinists like Tackle to refine their skills and prepare for cutting-edge ascents in the Greater Ranges. Countless difficult big-wall and alpine routes were established, and many remain as proud objectives for the modern climber.

Tackle was so fond of the place that he continued to climb there extensively after returning from a 1983 Everest expedition to become the first to climb the “six great north faces” of the Beartooths in winter. Local legend Alex Lowe established test-piece routes such as his Ursus Horribilis on the previously unscaled Bear’s Face and Come and Get It in Hyalite Canyon (among many others), simultaneously applying his skills to some of the groundbreaking climbs of the ’90s in places like the Himalaya. Little-known tales of Alex running free-solo laps on Tough Trip Through Paradise and Cardiac Arête—two of the hardest routes at Practice Rock—stand as a testament not only to his technical mastery, but his quiet and humble commitment to the craft.

Fast-forward to today, and the Beartooths are still a place ripe with potential for the development of daring, difficult routes all year round. On unclimbed ice flows, I have been lucky enough to experience a sliver of the spirit that defined the Dirty Sox Club members.

As climbing gains popularity, and online and print information becomes increasingly exhaustive, it warms my heart to know that there remains a place—in my backyard, nonetheless—that can still provide powerful, exploratory alpine experiences. Blank canvasses remain, awaiting the brushstrokes of adventurous climbers’ creative visions.

The story of the Dirty Sox Club is permanently woven into the fabric of climbing in the Beartooths, and their attitude and ethics live on to this day.

Unlike many of the country's great alpine climbing areas, exploration in the Beartooths has always been tight-lipped and exclusive.

I'm prone to romanticizing the past, but Tackle tells me, hunched over a burger and beer at the Hauf, that “we kind of fucked up.” He’s just finished a hike to Saddle Peak, has plans to go climbing tomorrow, and his eyes still glimmer when he recounts Beartooth climbs from decades ago. He expresses some regret over the elitist attitude of the Dirty Sox Club and for not making access to information more egalitarian.

Not one to look back and reminisce on “how much better things were” in the past, Tackle emphasizes the importance of focusing on our actions today and how they impact our trajectory for the future. In between bites, I ask him how he thinks we should go about finding and sharing information on climbs in the Beartooths.

“Do your homework. Talk to people. They’re usually willing to share. And then go find out for yourself what makes that place so special. Act accordingly.”

Climbing in the Beartooths is inherently self-selective. Long approaches, difficult rock quality, and challenging route-finding are just a few factors that have kept the place from ever bustling with climbers. Those who choose to climb there are doing so to find exactly what the Dirty Sox Club’s members sought: friendship, solitude, wilderness, and the unknown. They’re doing so without desire for external recognition.

So the next time you come back from a kick-ass—or ass-kicking—excursion in the mountains, forget your phone for a while and tell your friends about it in real life. Ideally over a beer at the Hauf.