Catch Me If You Can

Following the footsteps of John Colter’s famous escape.

The current was strong. I held onto the clothesline that had been strung across the river to aid our crossings. With each step, the river got deeper: knee, then thigh, then crotch. Finally—when I was just about up to my waist—I found myself struggling to hold on. I glanced downstream at the rescuers standing in the river, and wondered where I would float to if I lost my grip and slipped. After a few seconds that felt like an eternity, I began rising up and out of the river, shifting my focus to the shore.

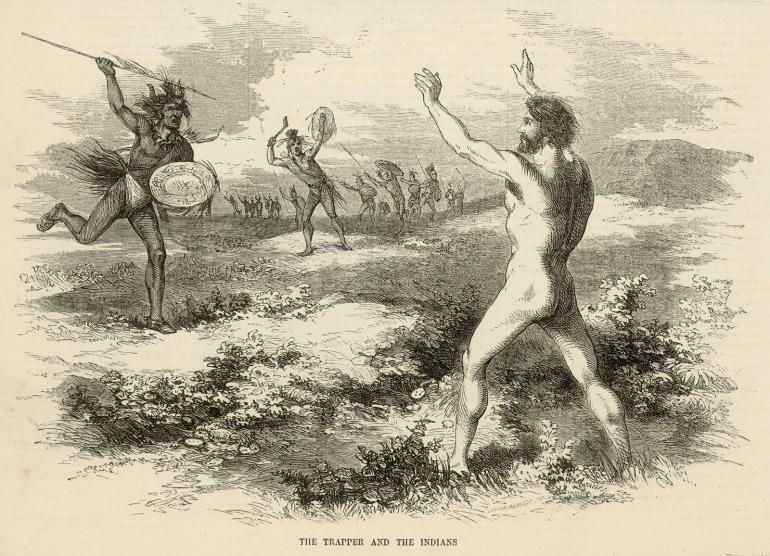

John Colter and John Potts had no lifeline, no rescuers downriver when, as they paddled the Jefferson near the headwaters of the Missouri, they were confronted by hundreds of Blackfeet. After shooting one warrior and resisting their entreaties to come ashore, Potts was riddled with arrows. Likely imagining the myriad of ways he might be put to death, Colter gave up and went ashore. Being stripped naked and given a running start was likely the best thing he could have hoped for. Somehow, it was all he needed.

The 47th reenactment of Colter’s run, now put on by the Big Sky Wind Drinkers, is civilized enough. Lined up along the road, we wait for a 19th-century mountain man to return from Rendezvous to his beaver traps and fire his .50-caliber Hawken black-powder rifle into the sky. A train passes us by as we wait; no Blackfeet warriors are in view.

After trekking more than a mile on pavement, we begin climbing a long, steep hill leading to a stretch of dry grasslands and cactus—country reminiscent of what Colter crossed as he raced from the Jefferson to the Madison River. The reenactment Colter is given a 100-yard head start. He is chased up and down hills throughout the race, and prizes are awarded to runners who pass him. As in all races, this is a battle for position. The only position the original Colter could afford to be in if he was to survive was first.

Expecting an ambush from the Blackfeet, Colter traveled at night through the mountains until he got beyond the area we now know as Bozeman Pass.

When I first ran this race back in 1983, there was no trail—only orange-topped stakes driven into the brush to point the way. Now, the path is so clearly marked with cairns that folks can focus more on the views and camaraderie. While we ran for miles, our stakes were low; none of us had to push to the point of spouting blood from our noses in a race against death. Sure, we were at risk of tripping over rocks on a steep downhill, but there was no threat of a spear ripping into our backs.

We ran to the river with nervous anticipation. It was always cold, but the water crossings added a memorable challenge to the race and made it stand out. In 1983, we made a beeline toward the river, running over the railroad tracks and crashing through downed trees and thick brush. After two racers sprinted in front of an oncoming train some years back, Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway officially forbade runners from crossing the tracks. Now a circuitous trail guides racers under them. Dipping under the railroad trestle, marked as Colter’s Beaver Dam, gave us our first feel of cold water and muck. A short burst of speed later, and we had reached the Gallatin River.

Nearly two inches of rain fell earlier that week. As the water made its way downstream, the river swelled to be deeper than I’d previously experienced.

Colter provided firsthand accounts of his race for survival. As the story traveled among mountain men, it was suitably embellished. In accounts I’ve read, Colter turned to face the one warrior who had outpaced all the others and was within range of spearing him. The warrior tripped, possibly from the exhaustion of the chase or from the disorienting effect of Colter’s bloody face. Colter grabbed the warrior’s spear and drove it through him, pinning him to the ground before continuing to the Madison. One version tells of Colter grabbing the warrior’s blanket before continuing; another said he was stark naked. Once in the river, one telling of the story asserts he hid in a snag, while another claims he swam up into a beaver lodge. In the account read at the reenactment, Colter found his way inside the trunk of a hollowed-out cottonwood.

As the water made its way downstream, the river swelled to be deeper than I’d previously experienced.

The frigid temperature of the Madison meant Colter would have had to keep himself out of the water, lest he become hypothermic as the Blackfeet scoured every inch of ground. Beaver lodges have shelves built in them that sit above the water line, so he could have stayed relatively warm and dry if that version is true. If he were lucky enough to find a hollowed-out cottonwood, that also might have worked. But we’ll never know for sure.

He emerged from his hiding place after dark and continued downriver for some miles. He had to make his way to Manuel’s Fort, a fur-trading post at the confluence of the Big Horn and Yellowstone rivers, some 150 miles east—in the fall of 1808, it was the only outpost of American civilization in the region. Expecting an ambush from the Blackfeet, Colter traveled at night through the mountains until he got beyond the area we now know as Bozeman Pass. He survived on roots for seven days and turned up at the fort emaciated, but alive. It is a great story of survival worthy of its many retellings and embellishments, and worthy of our race in his honor.

Once we left the river, we had to run on river stones for a short distance. Those stones were under a few inches of water this year, but then we turned, headed up the bank, and sprinted to the finish. For the fastest among us, the roughly 7-mile race and 1,100 feet of elevation change was over in 49 minutes. For the slowest, it took two hours and 28 minutes. I like to think Colter would have been glad to join in; he might even have been satisfied if he didn’t finish first.