A Long Walk in the Park

The unlikely but true tale of an early misadventure in Yellowstone.

In a time before GPS maps, technical hiking shoes, and all things Patagonia, a group of 19 men were tasked with exploring and charting what would become Yellowstone National Park. They would come to be known as the Washburn Expedition group. Among them was a man named Truman Everts, who joined the party at the youthful age of 54. Everts served as the Tax Assessor for the Territory of Montana—an unlikely resume for an explorer into the great unknown. But he had a horse, and, despite his lack of wilderness experience, he accompanied the group on their intrepid quest.

In early August 1870, the men loaded up their horses and set out to explore the area north of Yellowstone Lake, where they would follow the shoreline south with hopes of finishing the trek before winter set in. Just a week into the expedition, Everts earned the unfortunate title of “First Recorded Lost Person in Yellowstone.” He endured the next 37 days on an epic solo camping expedition.

In his own account, Everts claimed he wasn’t worried after being separated in the dense, overgrown pine forest; separations were common, but individuals were quickly located. Despite his optimism, Everts would not see such a favorable fate.

As night fell, he remained confident that he would reconnect with the group the following day. With ample sunlight to navigate, he set out in what he believed to be the correct direction of his party.

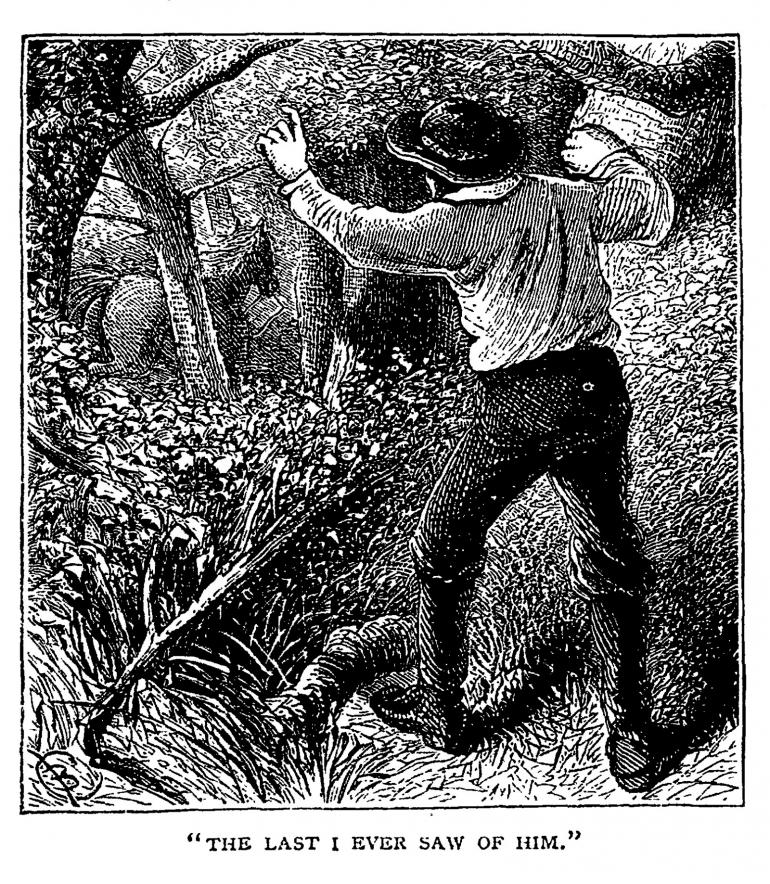

Navigating the heavily wooded terrain on horseback proved difficult, so he ultimately decided to dismount his horse and see what lay ahead. Untethered to a tree or hitching post, Everts’ horse quickly spooked and bolted, leaving him with nothing but the clothes on his back, a few knives, one opera glass, and an unhealthy amount of optimism that he would be located. “Even this dismal foreboding was cheered by the hope that I should soon rejoin my companions, who would laugh at my adventure and incorporate it as a thrilling episode in the journal of our adventure,” he recounted.

Everts’ horse quickly spooked and bolted, leaving him with nothing but the clothes on his back.

Three days later, and short on food, shelter, and dry clothes, Everts decided to mark his location, still confident his companions were nearby, searching for him. When he returned the next day to find an absence of response messages from his travel mates, the harsh reality of his solo adventure finally set in. “No one had been there,” he wrote. “My disappointment was almost overwhelming. For the first time, I realized that I was lost.”

Everts changed his survival strategy. As he searched for Lake Yellowstone, he stumbled upon what is now known as Heart Lake, where he spotted a man in a canoe in the distance. Fueled by a rush of hope, he bolted toward the shoreline, halting as he realized he had merely spotted a large pelican gliding on the water.

Hopes dashed, he took refuge for the evening at the base of a tree, where a bright-green thistle caught his attention. Yanking the plant from the soil, he discovered the root contained enough flavor to be considered “dinner.” The was later named Everts’ Thistle and can still be found growing in the Greater Yellowstone region.

Dejected from the day’s punishments, with a belly full of five-star thistle root and a bed of pine needles, Evert called it a night.

“No one had been there,” Everts wrote. “My disappointment was almost overwhelming. For the first time, I realized that I was lost.”

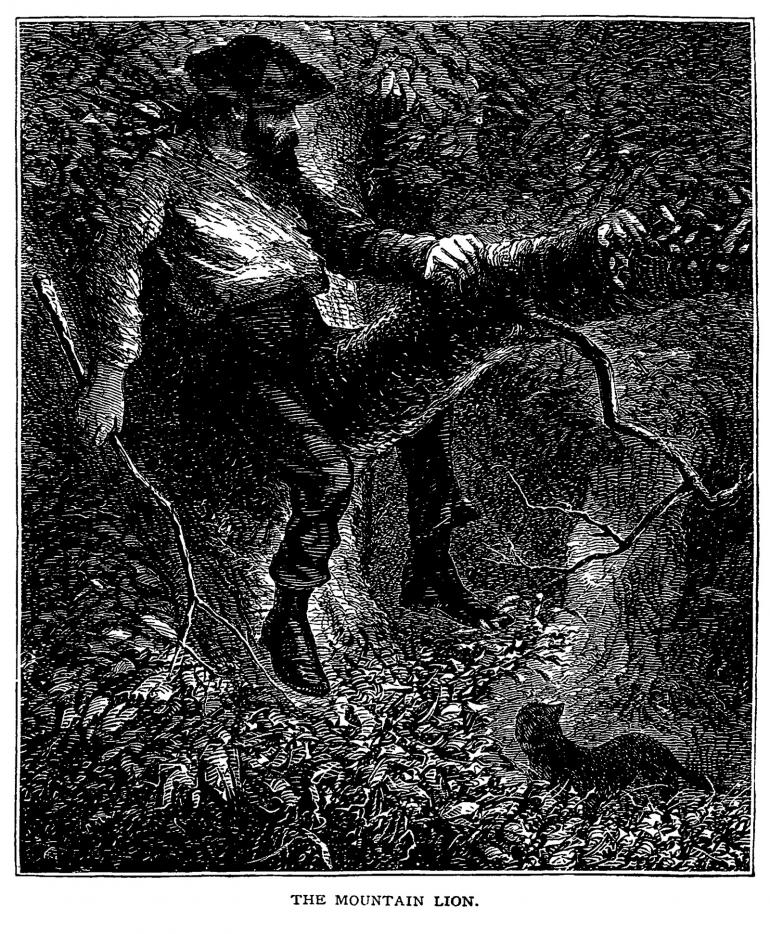

He was roused from his slumber by the screeching of a mountain lion. The cat yowled, announcing every stalking step she took toward him. Everts’ fight-or-flight response kicked in, and he scrambled up a tree trunk, seeking refuge in the high branches as the lion inspected his sleeping quarters below. Eventually, she moved along, allowing Everts to return to his quarters. There, in the hollowed-out tree trunk, he hunkered down for two days, waiting out a storm and growing increasingly desperate for warmth and sustenance. If only the horse carrying his supplies hadn’t abandoned him…

As he holed up in the bad weather, a stroke of luck hit him—a small bird swooped into his camp and rested on a low branch. With quick reflexes, he snatched it up and ate it raw.

When the storm finally passed, he headed north, setting up camp between hot springs and using the smelly thermal steam to keep the frostbite at bay. His plan proved effective, until the ground beneath him cracked, sending a blast of scalding water over his body and burning his hip.

With tattered clothes, a freshly burned hip, and dwindling hope, Everts continued the journey and set out toward the lake, wearing shoes fashioned from bark and scraps of his leather vest.

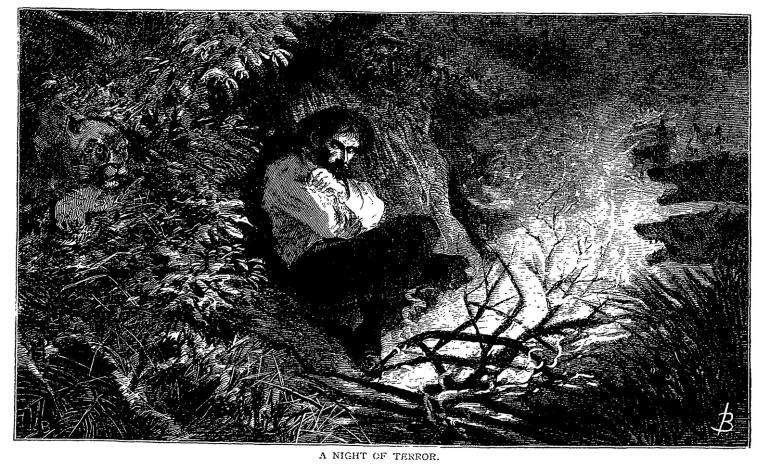

His blistering hip forced him to sleep upright, making rest elusive. As the cold nights wore on, he began to experience night terrors of animals on the hunt. One particular dream was so horrible that he startled himself awake, falling into the small fire he built for warmth and searing the flesh of his hands.

He was roused from his slumber by the screeching of a mountain lion. The cat yowled, announcing every stalking step she took toward him.

Bruised and burned, Everts mustered the willpower to continue his journey, and he finally found himself on the shore of Yellowstone Lake. It was there that he discovered the remains of his group’s camp. He scavenged a fork and a tin cup in the abandoned camp, but was unable to determine the direction his companions had traveled.

Unbeknownst to Everts, the men had left food and supplies among the trees upon his initial disappearance. But by the time he came upon the camp some 30 days later, the supplies were long gone, scavenged by animals. So Everts set off once again, this time to the north, to find his companions.

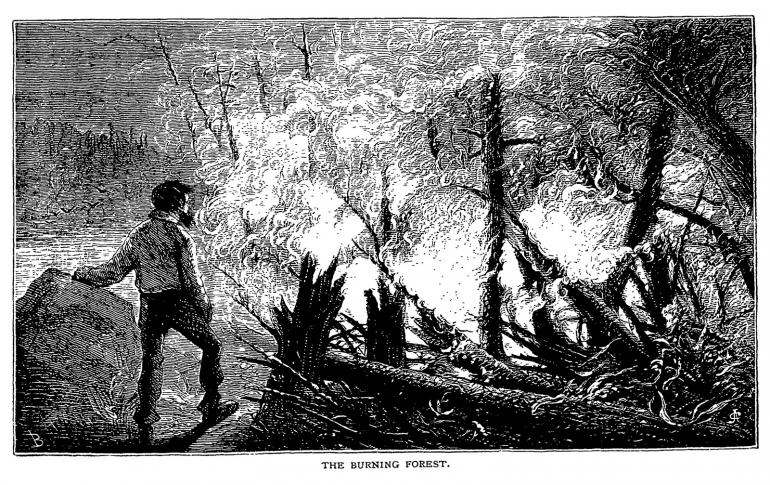

Now Everts slept more than he hiked, managing to cover only a few miles a day. Perhaps it was the delusion from the dehydration, but one evening, he dozed off after building his nightly fire, only to be woken by a forest fire growing around his camp.

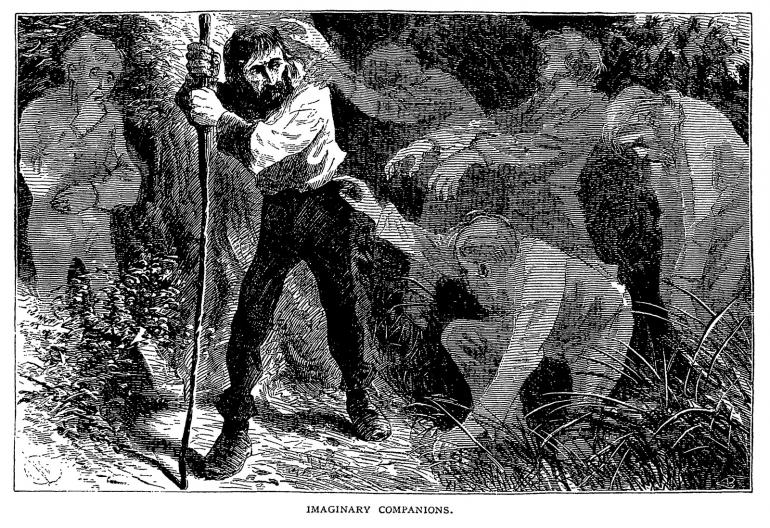

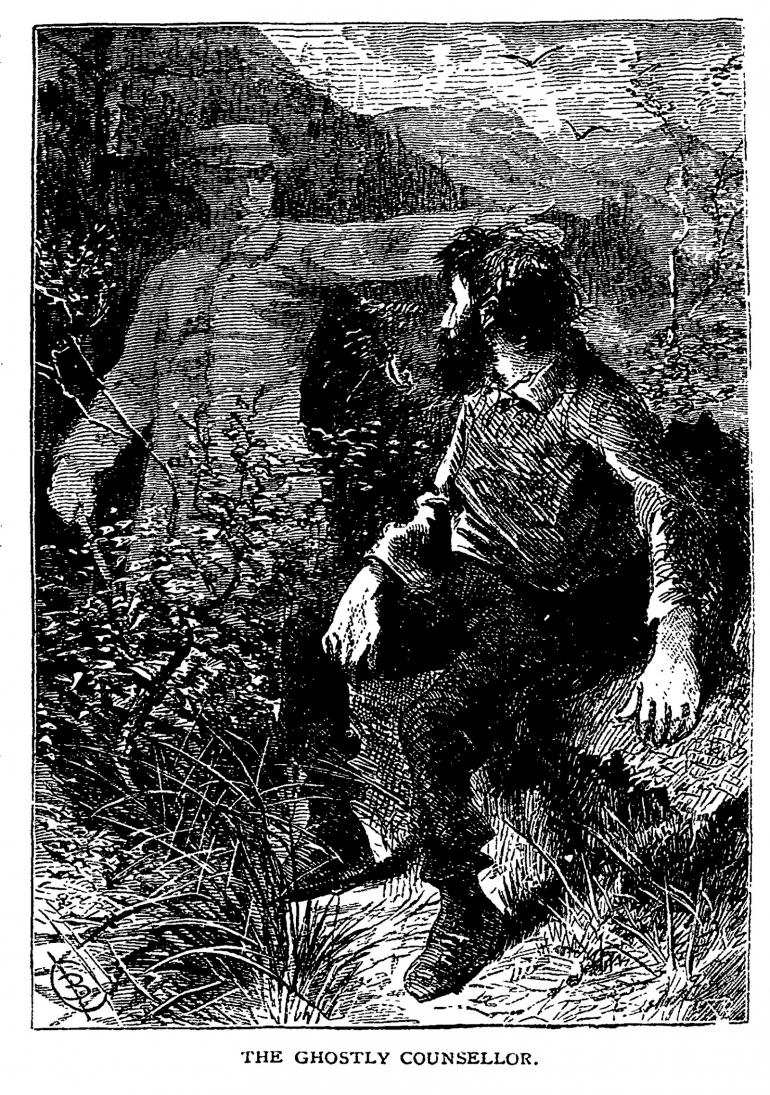

Soon, the night terrors turned to hallucinations, one of which told him to turn around and go back in the direction he had come, so he abided.

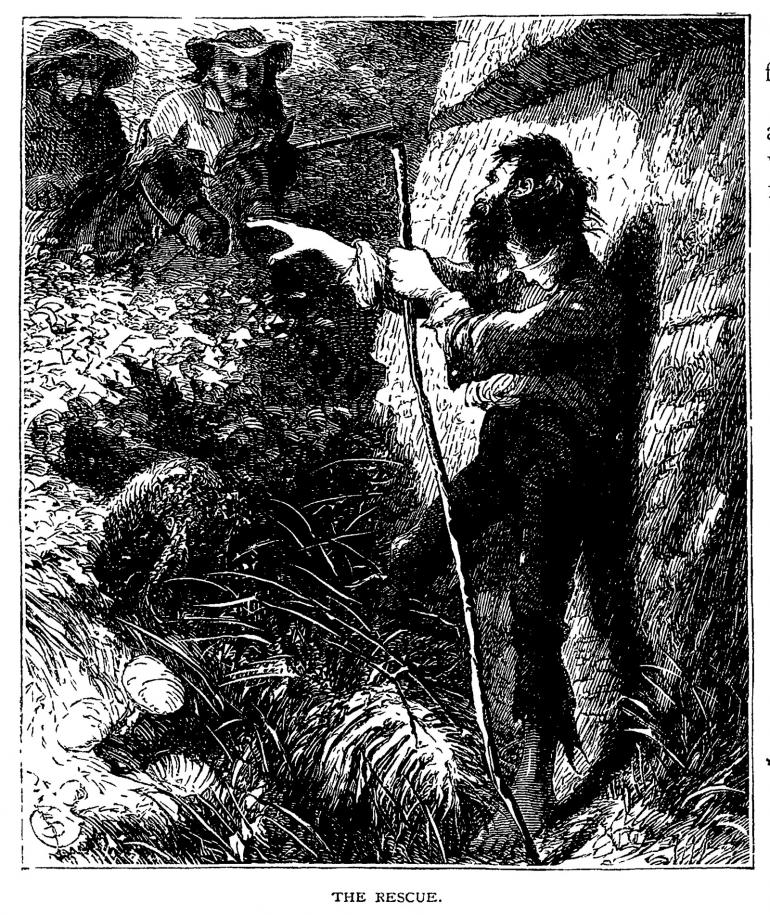

Convinced he was in his final days of life, Everts mustered what little energy he had left in order to continue his journey. Fifty miles north of his original location, after a total of 37 days missing, he was spotted crawling through the brush by two men sent to search for him. Barefoot, covered in burns and frostbite, wearing broken glasses, and weighing less than 90 pounds, Everts resembled more of an emaciated wild animal than a man.

The party had left food and supplies among the trees upon Everts' initial disappearance. But they were long gone by the time he came upon the camp some 30 days later.

The rescuers nursed him back to health, ensuring that he could make the trek to a logging cabin to more fully recover. There, he spent a few days chugging bear fat. Once he was deemed fit to travel out of the wilderness, Everts finally returned to his home in Helena.

Impressed by his ability to survive, President Theodore Roosevelt nominated Everts to be the first Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park. He declined the position, allegedly due to a lack of pay, and relocated to Maryland, where he worked for the U.S. Post Office and fathered a child in his late seventies. He would live until 1901, when he passed from pneumonia at the age of 85.