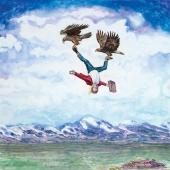

Passing the Torch

Forging new paths into old places.

“Leave it as it is… keep it for your children, your children's children, and for all who come after you.” —Theodore Roosevelt

The trail to Teapot Camp peters out after the second creek-crossing. Maybe the trail crew gave up, their crosscut saws no match for the old, burnt deadfall littered across the path. Or they decided it was hopeless; more trees will fall next year, anyway. Regardless, there’s no trail for the next 12 miles, only a mess of charred logs, most at that awkward height: too high to hop over, too low to crawl under.

After navigating a log jam over the third and largest creek-crossing, a hiker determined to find the camp must leave the streambed altogether. There’s a 1,500-foot climb, a tree-strewn bench, and a subsequent descent into a parallel drainage. Only then, if he’s observant, will the explorer spy the fire ring. It’s tucked away in a grassy clearing above the floodplain, cliff-bound on two sides and a jumble of boulders on the other. If he pushes through a nearby patch of willows, he’ll also discover a pair of rough-cut wooden planks and the rusted remains of two 55-gallon drums, jagged holes cut into the sides. Perhaps they were animal snares at some point in time, now repurposed as seats for late-night storytelling.

The tracks of those who have walked every finger-ridge and explored every tributary will be washed away, the fire ring overtaken by grasses and willows. And yet the teapot will remain.

He’ll have to look closely to discover the camp’s namesake item. The old aluminum kettle, bottom blackened from countless hours perched atop flames, is stored in a crevice in the cliffs, lest something happen to it over the winter. But in the last four years, it’s never moved, except during an annual visit by a trio of young men, for whom it has heated the water for countless dehydrated meals, oatmeal packets, and hot-water bottles.

How or when it got there is a mystery. Before the forest was torched some 15-odd years ago, the area was a venous network of pack trails. Likely, Teapot Camp was the hunting base for a group of mountain men, who every year packed in to chase animals around the hills, recline on barrels, and sip whiskey. But once the fire tore through and the snags started falling, they could no longer ride their ponies into camp. And so they abandoned it, and the teapot remained unused for nearly two decades, until the young men happened across it on a spring antler-hunting expedition.

Their first trip was six miles in, a solid jaunt at the time. But then, through spotting scopes, they spied a group of bull elk, some of the biggest they’d ever seen, on a timbered bench in the distance. The following year, they bombed in, stopping only to refill water bottles in the cold spring runoff and grab Snickers and Oreos from their packs. That evening, they stumbled across the teapot, tucked into the base of the cliff.

Teapot Camp will serve as their own for another decade, maybe two. Until their bones are too creaky to crawl over deadfall, or they have families and can only escape for a long weekend at a time. It will be their place for solace and reflection, where they can escape the city for a week on end: a reset in the fresh spring air. But more so, it will rest in the back of their minds, a feeling that can be slipped into for a few seconds, or minutes, when needed. The smell of campfire smoke mixing with wild onion grass, the chalky feel of charcoal and ash from the burnt forest covering every speck of skin—it’s all there, ready at a moment’s notice. It’s the kind of spot that warrants protection by way of secrecy, and there’s comfort in knowing anyone who finds it will be equally enthralled—common knowledge amongst those who explore.

But metal will outlast flesh, time and again. The tracks of those who have walked every finger-ridge and explored every tributary will be washed away, the fire ring overtaken by grasses and willows. And yet the teapot will remain, waiting in the same crevice for the next group to find, stories of past adventurers held tight in its soot coating. Perhaps it will be next year—or in 50 years, once the forest has grown back and the trail is again cut-out. It could be another reckless bunch, to whom the burnt logs are nothing but an exciting challenge, or the grandchildren of the original horse-packers, having heard stories of Teapot Camp told around the campfire from the time they were little. Regardless, they will inevitably romp in the same hills, drink from the same creeks, and boil water in the same kettle, adding their own layer of soot to that from generations past.