Unsafe Passage

An overdue call for wildlife crossings on Hwy. 191.

In a 2019 video shared by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, waves of antelope rush across an overpass west of Pinedale during their annual 200-mile migration. As the critters run over the grassy bridge, drivers zoom by beneath them at highway speed. This section of Hwy. 191 has historically been one of the deadliest sections of the pronghorns’ journey, with hundreds of animals dying each year due to collisions with fast-moving cars. But since the game passage was installed in 2012, wildlife-vehicle collisions in the area have decreased by 85 percent.

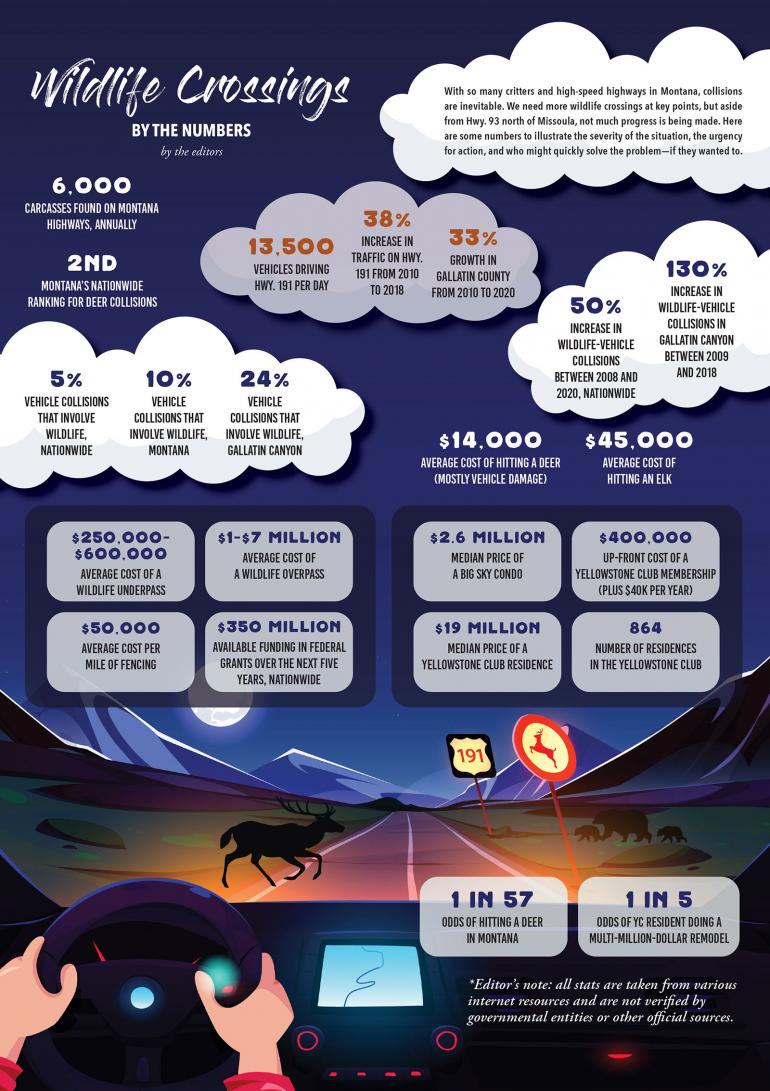

A few hundred miles north, the same highway winds through Gallatin Canyon in a section of road that accommodates more vehicles than any other in Montana. The black strip between Four Corners and Big Sky sees as many as 13,500 vehicles per day. If you’re a deer or an elk hoping to cross the road along this stretch, good luck.

A wildlife crossing project can’t be completed with pocket change.

For years, Montana has ranked number two in wildlife-collision rates (second only to West Virginia), and a huge portion of these occur where 191 cuts through the wildlife-rich Gallatin Canyon. Murmurs of installing an overpass, underpass, fence, or bridge have been heard for a long time, but the rubber has yet to meet the road. Why is our state so far behind, especially in a category where our neighbor Wyoming is leading the way?

That’s not to say we don’t have any wildlife accommodations. There are 81 on US Hwy. 93—the road running north-south from Eureka to Sula through Missoula—and an additional 40 scattered elsewhere throughout the state. But though highways 93 and 191 see comparable traffic, it’s noteworthy that 93 has received the bulk of attention.

That discrepancy dates back to the ’90s, when the state was kindling plans to widen the highway north of Missoula. Being that the motorway slices through a reservation, the agency needed a sign-off from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes. But the tribes wouldn’t grant the green light unless the projects reduced the roadway’s impact on wildlife. Smart move, eh? The obvious way to do so was to install various wildlife crossings such as overpasses, culverts, and exclusionary fences that funnel animals into particular points. The tribes and the state worked to an agreement, and development began in the mid 2000s. There are now 39 wildlife crossings on the Flathead Reservation, with dramatic success in reducing animal-vehicle collisions.

The black strip between Four Corners and Big Sky sees as many as 13,500 vehicles per day. If you’re a deer or an elk hoping to cross the road along this stretch, good luck.

The same sort of collaborative achievement can be seen in Wyoming, where state agencies have taken a proactive approach to both wildlife connectivity and public safety for over 50 years. The state built its first wildlife crossing in the 1970s. Additionally, the state holds conferences where the Department of Transportation, Game and Fish, and other nonprofits work together to identify priority areas and subsequently put action in motion (Montana held their first conference in 2018). The state’s concerted effort has been recognized nationally, resulting in grant money to help fund the construction of projects. Last October, Wyoming announced the completion of the Dry Piney Project, which included nine underpasses and 17 miles of fencing. The development cost $15.1 million, of which $14.5 million was covered with a federal grant.

So why is Montana taking so long to catch up? It boils down to a lack of foresight, and a lack of funding. Plans, however, are in motion. Recently, the Department of Transportation, FWP, and a fellow nonprofit teamed up to form the Montana Wildlife & Transportation Partnership, a group designed to “inform and implement collaborative work” regarding wildlife-highway conflicts. Last year, the partnership created an “interactive resource tool” to help distinguish areas of concern. On top of that, the state has allotted $500,000 a year to conduct engineering and feasibility studies on proposed project sites. Last November was round one for the initiative. Only two applications were submitted.

There is also citizen science being done to help gather facts and get the ball rolling. The Center for Large Landscape Conservation, a nonprofit focused on restoring ecological connectivity, teamed up with Montana State University to create a smartphone app designed to gather information about wildlife movement patterns. The group also penned a 140-page report on wildlife mortality and driver patterns specifically for Hwy. 191 and Hwy. 64 (the road running up to Lone Mountain).

But installing a wildlife crossing isn’t as simple as picking an area and breaking ground—not to mention, selecting a spot that will actually be conducive to wildlife using said crossing. First, there’s the issue of what and whose land the accommodation goes on. Both sides of a road need to be accounted for by either a public agency or an easement. From Four Corners to the mouth of Gallatin Canyon, all the land surrounding 191 is private, most of it with different owners on opposing sides of the road. To make any sort of progress on site selection, both holders would have to agree to easements on their land. If that hurdle can be routed, next comes the financial barrier. Culverts can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and overpasses are more in the multi-million-dollar range. Those numbers don’t even include the fencing necessary to prevent animals from crossing at other spots. According to the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, 1.5 miles of fencing are required on both sides to yield effective results.

All this is to say, a wildlife crossing project can’t be completed with pocket change. But that’s what we have the U.S. Congress for, right? Two years ago, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed, providing all sorts of funding for all sorts of programs, including a Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program, which allocated $350 million for improving wildlife connectivity and reducing vehicle-related collisions. For local and state agencies seeking financial assistance, it lowered the bar tremendously. The money was slated to be released in five rounds through competitive grants. The first round of $110 million was divvied out in December. Nine million was awarded to Montana.

No doubt, there are plenty of agencies and entities lickin’ their chops to get a hand on some of this cash. But in order to win a grant, you’ve gotta have a compelling case. With a problem as blatant as Gallatin Canyon, you’d think the prospect of Hwy. 191 getting some of these funds would be pretty high. Think again. $420,000 was granted toward a feasibility study on I-90 between Missoula and Garrison. The other $8.6 million was granted to another overpass on Hwy. 93 north of Missoula, where six grizzlies have been hit since 1998.

The Department of Transportation, however, did apply for a project on the Cougar Creek Bridge near Hebgen Lake, but funds weren’t granted. Fortunately, four rounds of funding remain, so there’s still hope for projects in southwest Montana. For now, though, not a single wildlife crossing exists between Bozeman and Big Sky. The commute remains one of the busiest in the state—and one of the deadliest to our deer, elk, and other wild neighbors.

Perilous Pathway

by Fischer Genau

South of Gallatin Canyon, another stretch of Hwy. 191 poses a serious danger to wildlife. Migratory bison frequently cross the road between West Yellowstone and Gneiss Creek, and in December 2022, 13 were killed by a semi-truck just north of the Madison River.

With nearly five million visitors to Yellowstone Park each year, wildlife there is increasingly at risk. Along with the Cougar Creek Bridge project that’s currently on hold, several other efforts are underway to provide safe passage to migrating bison, as well as moose, elk, wolves, grizzly bears, and other species threatened by traffic in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Buffalo Field Campaign (BFC) has recorded over 20 years of animal activity in the region, and they’re analyzing this data in a study with Rutgers University to determine where wildlife crossings would benefit the greatest number of animals. They plan to use their findings to guide legislative action and secure funding to build these corridors. The group is also considering the use of active animal-detection systems that would alert drivers when wildlife is present.

BFC has partnered with Gallatin Wildlife Association to form another group, West Yellowstone Wildlife Crossing Coalition, that aims to implement wildlife-crossing structures through public outreach and collaboration with other agencies and NGOs.

To get directly involved with wildlife-crossing road studies, download the “ROaDs” form through the free smartphone app ArcGIS Survey123. Alternatively, explore the Montana Wildlife & Transportation Analysis Tool and provide feedback at mdt.mt.gov. For more information on wildlife crossings around West Yellowstone, visit buffalofieldcampaign.org.

Video courtesy Explore Big Sky