For Whom the Bear Bell Tolls

Clapping, singing, and self-loathing in bear country.

“Avoid the meadow ahead,” two hikers, hurrying toward me from the opposite direction, warned. “There’s a bear with her cub.” Of course, I thought. Not even James Bond, with the free world at stake, would charge ahead.

So it came as a shock when I assured myself, I can handle this, and continued toward the meadow with the confident stride of Yukon Cornelius rushing the Abominable Snow Monster in its cave. My hubris sprigged from a lifetime of scaring bears off my cabin’s deck via loud noises: clapping, banging kettles, shouting “Hey!” I, or so I foolishly believed, understood their weaknesses.

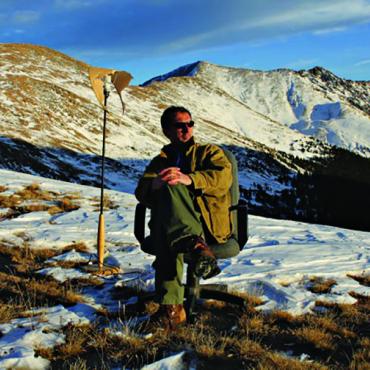

Plus, I was tired. After hiking most of the day on a trail that included 2,800 feet of elevation gain, I was desperate to return to my tent. With approximately two hours of hiking left, I was in no mood for waiting the bears out.

And so it was under this contorted logic that I, without pepper spray or weaponry, approached the alpine meadow with the defense plan of a bear bell. It had to work. There was no Plan B. Nor was there a cabin to flee into should my loudness fail.

The reality of my idiocy made me so angry that if I’d had pepper spray I would’ve used it on myself.

The meadow was approximately 200 yards wide, hemmed by forest on three sides and a steep open slope on its west side—indicative, perhaps, of an avalanche chute. Before entering, I clapped maniacally, like one of those organ grinder monkey toys, hoping to stir movement and gauge the bears’ location.

But nothing. Not even a sound. Maybe the bears had fled? Maybe, despite all better judgment, it was safe to proceed?

As I moved forward into the clearing, still clapping, for reasons that escape me, I began singing Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night.” Good God, I wondered. Am I attempting to scare these bears or annoy them? After 30 yards, I stopped to scan and listen. Again, nothing.

I repeated this—irritating loudness followed by assessing silence—several more times until I was close to where the trail disappeared back into the forest when, suddenly, I heard claws on a tree. There, about 50 yards ahead, was the cub, followed by her mother, clambering up a ponderosa pine.

I can’t be certain but I’m guessing the bear, from its elevated vantage point with a clear view of me, either assessed “That’s the jackass I’m fleeing from?” or mistakenly heard me shout, “I’m with Cub Social Services!” Whatever the reason, it suddenly began descending with the speed of a crazed chipmunk before disappearing behind a canopy of smaller trees that walled my view.

Fear jellied the brain. Where is it, I wondered? Still in the tree? On the ground preparing to charge? The reality of my idiocy made me so angry that if I’d had pepper spray I would’ve used it on myself.

While mulling this I, out of habit, reached for the small, green plastic squirt gun I always pack when hiking or backpacking to cool off and doused my face. I can’t die like this, I thought. Especially not while holding this squirt gun. My name will become an international punchline, on par with Grizzly Man Timothy Treadwell, when investigating authorities incorrectly deduce I tried to pistol-whip a raging 500-pound bear with a 49-cent squirt gun.

It was then, finally, that survival mode kicked in. I, with eyes submissively looking down, slowly backed away from the hidden bear’s general direction, back toward the other side of the meadow.

The retreat lasted about 10 minutes, but felt like 19 hours. To distract the mind, I gave thanks for being alive, unharmed, and for the eventual two-hour hike ahead—the perfect amount of time for rehearsing my Darwin Award acceptance speech.