On the Flip Side of Town

Walking the back-alleys of Bozeman.

Cottonwoods extend overhead, leaves scattering the sunlight. It’s cool in the shade. I take a seat on a log beside a creek. The water’s burbling trickles through my brain, draining thoughts of exhaustion after 20 miles of walking.

I force myself to stand and walk a few feet farther into this foyer of forest. It seems to enclose me, and I wonder why no one else is here enjoying a moment of blissful shade.

Suddenly, I am jolted out of my revery by barking and snapping jaws. I scramble up the bank and shuffle on, following the anti-grid of dirt paths tucked within the city.

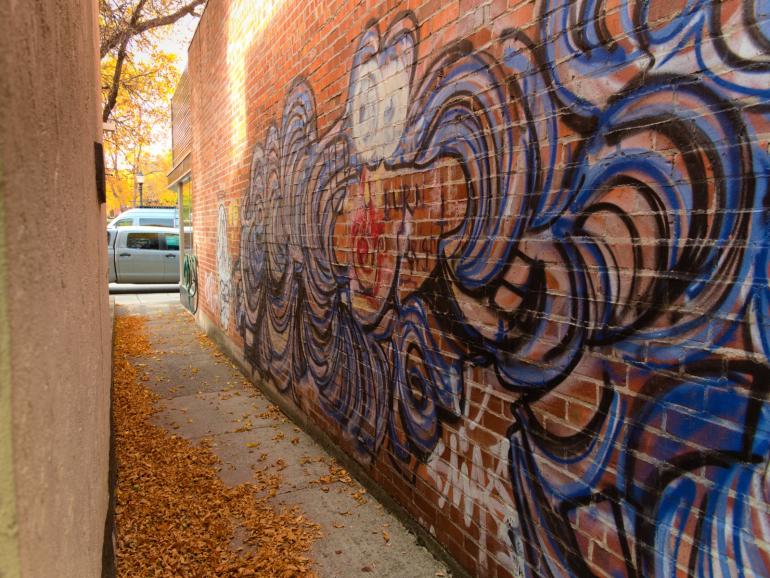

In Bozeman, offset from the city streets by half a block, lie the alleyways: a nearly abandoned world of garbage cans, wood scraps, paint cans, wildflowers, and surprisingly nice footpaths. Here in the city center, you can stare a half-mile down a straight path and see no other human.

I’m going behind the scenes today to survey Bozeman’s backwaters. I’ve lived here for a few years, but I sense that there is more beneath the surface, waiting to be discovered. Tourists explore by seeing a city’s sights; inhabitants explore by seeing the everyday. How adventurous can I get within the city limits? Early in the morning, with boots laced and a pack on my back, I slip out the gate and into the underworld.

The distant ridgelines and peaks that usually serve as landmarks are obscured by the endless repetition of fences, and tracking my progress is difficult.

Except for a few squeezes along Main Street, the alleys are gravel roads the width of a garbage truck, betraying their main purpose. Blue and green bins dot the dirt like cairns. I will follow these trail markers as far as they’ll lead. It’s a journey that will ultimately take me 13 hours, 34 miles, and deposit me back where I started—tired, limping, but smiling.

The view of the alleyway in front of me is blocked by fences, houses, and trees, leaving only the path in front of me and the sky directly above. I quickly enter a state of simple observation. I hear power lines buzz. A distant airplane. I see prayer flags. Stolen road signs. A poetry post for walkers-by. Greenhouses. A wheelchair inexplicably rigged up to a wheelbarrow. Canoes. Everything comes and goes, the sound of boots on dirt the only constant—keeping me grounded.

Near the university, some back yards are meticulously well kept. Summer sunflowers burst over recently erected fences and watered grass. Tomatoes lounge in their own weight, confused at the sunflowers’ need to stand up straight. Other lots feature unkempt lawns strewn with beer cans, with trampolines and decrepit picnic tables in lieu of gardens and shipshape patios. I feel like a critic, bestowing awards for these gems of commitment hidden between disheveled squares, whose messiness is also a kind of beauty. The disjunction sings a harmony throughout this part of town.

I am lost, flitting down pathways too small for my hastily-made map to display.

Wildlife is limited to magpies, ravens, roaming cats, chipmunks, and the occasional bunny—just as startled by me as is the occasional homeowner in her back yard. The distant ridgelines and peaks that usually serve as landmarks are obscured by the endless repetition of fences, and tracking my progress is difficult. I latch onto the sound of child-pitched yells from a soccer camp, which fade in and out of my separate, connected world. The hollering is appropriate given the backyard scenery of childhood merriment. It reminds me of when I was a kid; when the world was an exciting place to explore every day.

I arrive at Main Street after 15 miles. Cars are more numerous. Large dumpsters displace the garbage bins. Tarmac reflects heat from the sun. Aside from magpies and ravens, wildlife vanishes. The noise of construction feels pressed into my sweating skin. New development reminds me that I’m not native here; I’m an outsider within a much larger city. When I reach dirt tracks again, I’m relieved at the familiarity. This transformation spurs me on.

The walk has the quality of a trail through a dense forest, whereupon there’s a clear path—though not necessarily a clear direction. I see both familiar and new sights all at once: the trees and the spaces in between.

Occasionally, I am at the height of adventure. I am lost, flitting down pathways too small for my hastily-made map to display. I’m poking around construction zones and the backsides of housing complexes. How far out of my comfort zone can I get? Completely.

Today is a study in depth, seeing new things but never moving far from the start.

I feel like a deer in the road: wide eyed, overwhelmed. This is why I stop at the stream, wondering at the seemingly endless trees. After the unforeseen length of time it’s taken to walk my backyard alleys, I don’t see why they can’t extend forever. Most explorations are an education in distance, measuring length from one point to another. Today is a study in depth, seeing new things but never moving far from the start. Walking every alleyway is an education in where I live, beyond what I am used to seeing.

I’m not walking where no one has gone before, or where it is difficult to go; rather, seeking out exactly where people do walk—if only to take out the garbage—and stringing those paths together to make a route that may, through relentless recycling, be somehow original. Somehow my own. I’m adding my flair, finding overlooked paths. I’m turning toward what I usually don’t see.

I feel connected to people as I observe the rhythms of the day. The evening is marked both by lengthening shadows and people and music filtering into back yards.

The sun sets as I near my house, snaking through the final alleys. My mind relaxes as I make my final turn; the work of navigation is over after 34 miles. Reflecting on my walk, I don’t feel like I’ve found any specific revelation—I’m much too tired for that. But the world feels different, as if when I wake, I’ll be somewhere whole—somewhere buzzing and vibrant with the knowledge of what’s behind it, like I’ve peered through a microscope into a drop of water and seen something common with a new depth.

Suddenly, I realize I’ve overshot my fence and walk a few steps back to it. I lift the wooden stopper and let the gate fall inward. It is odd to see my own house as one of the many back yards, one of the places I’ve critiqued and labeled as a litter-strewn college pad or a well-kept family abode. I fall somewhere in between, and I realize after walking the in-between lines that this is where I am. For a second, it’s unrecognizable; but before long, it feels more like home than ever before.