Bunsen Burner

A skiing pilgrimage in Yellowstone Park.

Have you ever gone on a pilgrimage? You know, a journey into terra incognita. Maybe you were seeking an enlightened understanding of yourself. Or even of life in general. It could have been a cloud-shrouded trek on the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu. Or a more divine journey to Bodh Gaya in India. Or maybe it was something more irreverent, like a peek into the Elvis’s bathroom at Graceland in Memphis.

But if your spiritual heart lies more in the natural world, there is a wealth of pilgrimage opportunities right in our own back yard. One such voyage that has become an annual ritual for me is the circumnavigation of a nearby mountain: the iconic Bunsen Peak. However, this one isn’t done on foot, but on skis.

Topping out on Snow Pass can be a rude preview of the windy conditions to come.

The Snow Pass & Bunsen Peak Loop in Yellowstone meets my criteria for a pilgrimage. More than just a ski outing, it’s a sojourn into vast, sublime terrain, often with moments of reflection, and on occasion, transcendence.

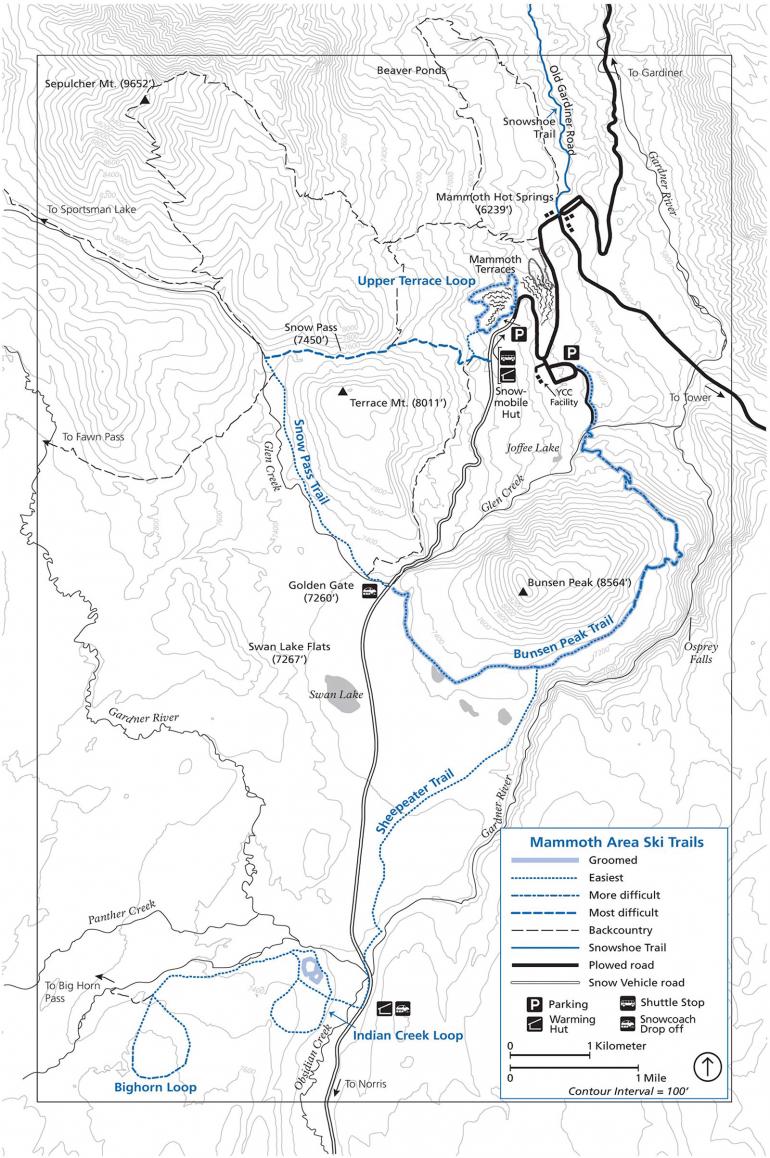

The 10.5-mile loop begins at Upper Mammoth Terrace, just south of the Mammoth Hotel. Even under the best of circumstances, it’s a big day, and you’ll need to pack for it—snacks, liquids, perhaps extra clothing like dry gloves and hat, hand warmers, headlamp, and an emergency blanket. Don’t forget ski goggles. You might need them on Swan Lake Flats. And in the spring, bring your bear spray. Remember, you are in Yellowstone, not on the Camino de Santiago.

I recommend metal-edged skis that are wider than what you would use on groomed trails. And even if you have waxless skis, a small selection of waxes—especially liquid glide wax for sticky snow—could prove essential.

The route begins innocently enough on the Upper Terrace ski trail. It is a rolling, groomed stretch, and a good opportunity to adjust your gear before things become more feral. After a quarter mile, a trail marker to your left indicates the route to Snow Pass. Take it. A hundred yards further, you leave the geothermals and enter the lodgepole forest. After a couple of minutes, you’ll reach the official trailhead. A sign illustrates Mammoth area trails as well as reminding visitors: “This is Grizzly Country.” You would not see that on the way to Lourdes!

The trail splits here. Head right toward Snow Pass, which is about a mile in distance and 700 feet higher in elevation. The trail immediately begins to climb. If you have skins, the right wax, or waxless scales that do the job, it’s not too arduous. Lacking these, it can be a slippery slog. In fact, between the steep incline and narrowness of the trail near the top, you may have to remove your skis and trek the last 100 yards on foot. There is no shame in walking. Indeed, many pilgrimages are done on bended knees.

Topping out on Snow Pass can be a rude preview of the windy conditions to come. Take a moment to gather yourself and admire the view. Gulp some water. Nosh on an energy bar. You may have shed clothing on the climb. You may want to put it back on. And make sure those goggles are handy.

From the top of the pass to Swan Lake Flats is a mostly downhill roller-coaster ride. But when you break out of the trees, beware of possible patches of windblown bare ground. They can bring you to a screeching halt, or worse. Remember what the Grateful Dead warned: “When life looks like easy street there is danger at your door.”

Upon reaching level ground, you are at the edge of Swan Lake Flats. This is where it can get interesting. Sometimes a slice of heaven. Other times, a frozen hell.

Someone in that party asked me how long I’d been breaking trail. Before I could respond, the person behind me blurted, “His entire life!” While totally undeserved, I consider that the best complement I have ever received.

The trail across the Flats skirts the base of some low hills and is marked with plastic poles. But they are placed far apart and if windy—as is often the case—the tracks of previous skiers can be blown in and the poles difficult to see. I once ran into a couple from Georgia who were heading in the exact wrong direction. They reminded me of the lone penguin in the Werner Herzog film, Encounters at the End of the World, that was aimlessly shuffling inland away from the ocean and toward certain doom. I politely set them back on course. We’re all in this together.

If it’s calm and sunny, snow conditions are good, and the trail is already broken, crossing the Flats can be pure bliss. Snow-covered hills to the south might beckon tele skiers. And behind those, the stunning Gallatin Range stretches as far as one can see. You might hear the plaintive howl of wolves, or the yelping of coyotes. Or it may be as silent as an ashram.

On the other hand, if it’s windy, or the snow deep and untrodden, it can get adventurous, even—dare I say—life-threatening. Once, with a friend, I skied the Flats in harsh whiteout conditions. At one point he shouted, “We could be in f***ing Siberia!” It was brutal. Thank God we had goggles. During another crossing, though a bluebird day, there was a foot of fresh, heavy snow. I was in the lead. About halfway across, much like the meeting of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads in Promontory, Utah, we ran into skiers coming from the opposite direction. Someone in that party asked me how long I’d been breaking trail. Before I could respond, the person behind me blurted, “His entire life!” While totally undeserved, I consider that the best complement I have ever received, and I try to live up to it.

It’s 2.2 miles across the Flats with some slightly hilly terrain near where the trail crosses the road connecting Mammoth with the Park’s features to the south. I used to make snarky comments about that road, as well as the snow machines that traverse it. No more. I now view it as a sometimes much-needed escape route back to my vehicle when weather, snow conditions, or oncoming darkness make continuing around Bunsen a less-than-wise decision.

After crossing the main road, the route around Bunsen proper is on a narrow lane that is open to bikes during summer. While groomed for skiers come winter, stiff winds as well as divots from wandering bison can rough it up to the point where skate skiing can be difficult. There are also a few downhill sections where those wider skis with metal edges will definitely come in handy.

A short way up this trail is a place I traditionally stop for one last view of the grand expanse of Swan Lake Flats and the mountains beyond. I like to silently thank those who had the vision to set aside this sacred ground as the world’s first national park. I acknowledge the native peoples who traversed the area long before them. And lastly, I honor the four-leggeds that have called this place home for millennium, and marvel that they are still here. I feel humbled by the immensity of the landscape, and on rare occasions, feel truly at one with the entire tableau. That sends shivers down my spine, but brings peace to my soul.

There is one sharp curve that comes close to the edge of the deep and steep Gardiner River canyon. The chances of missing the curve are probably slim. Though I’ve always thought it would be one hell of way to exit planet Earth.

If you started the trek at, say, mid-morning, chances are it’s past 1:30pm by the time you’ve reached this point, and you still have a good five miles to go. Time to keep moving. The next three miles are flat or rolling, in and out of trees. It’s a good stretch for putting your head down and stoically picking up the pace. That is until you run into those two or three bull bison that seem to be a permanent fixture on this section of the route. And they don’t like to move for anyone. If they’re 25 or more yards from the trail: no problem. But they are often on the trail, or just feet from it, and seemingly asking, “Do you feel lucky? Well, do ya’, punk?”

Sometimes you see the tracks of previous skiers who have trudged off-trail to give the bison a wide berth. That’s what I do. I do not want to be the person who goes viral on YouTube flying through the air after a belligerent bison decides his personal space has been violated.

About two miles from trail’s end, a sign warns of steep downhill. Woo-hoo! Snow conditions will dictate whether it’s exciting, or in some short stretches, somewhat terrifying. There is one sharp curve that comes close to the edge of the deep and steep Gardiner River canyon. The chances of missing the curve are probably slim. Though I’ve always thought it would be one hell of way to exit planet Earth.

Assuming you negotiate this curve, the Gardiner Canyon overlook is an excellent place to stop for one last snack, photo, or just a pensive scan of the wonders of Yellowstone. Another 3/4-mile of downhill fun and you cross Glen Creek, a short distance from the end. After a herringbone climb up the other side, you traverse a small meadow and pop out at an employee-housing complex. If you left a car there, it’s about a mile drive to where you began. If not, your final challenge is hefting skis and poles and plodding up the road, hoping that someone, probably a Gardiner resident who knows exactly what you have been through, stops and says, “Hop in!”

I’ve completed the loop in as little as 5.5 hours. And in as many as 8. Once, with a large group that included some novices, it was dark by the time we finished. One of the guys was pretty roughed up. When he arrived home things only got worse. He received word that his father had passed away and he had to rush to the airport to fly home to be with family. When I learned of this, I contacted him to apologize for putting him through the ordeal. Much to my surprise, he thanked me and said that the physical challenges he faced that day had prepared him for the mental challenges associated with the loss of a parent. I remember he used the words “altered state of consciousness” to describe the experience.

I’m starting to believe that with the right attitude, all of our outdoor adventures can become a pilgrimage of sorts.

Whether this loop takes on the character of a pilgrimage, or just another ski outing, may depend on many factors, the most significant being your own personal attitude. After all, the spiritual nature of a place is really in the eye of the beholder. Or maybe better said, in the soul of the beholder.

I’m starting to believe that with the right attitude, all of our outdoor adventures can become a pilgrimage of sorts. That is what I’m striving for, anyway. And as the saying goes, a journey of a thousand miles begins with one step—or one stride on skis, as the case may be.