Powder Pioneers

Bozeman's original extreme skiers.

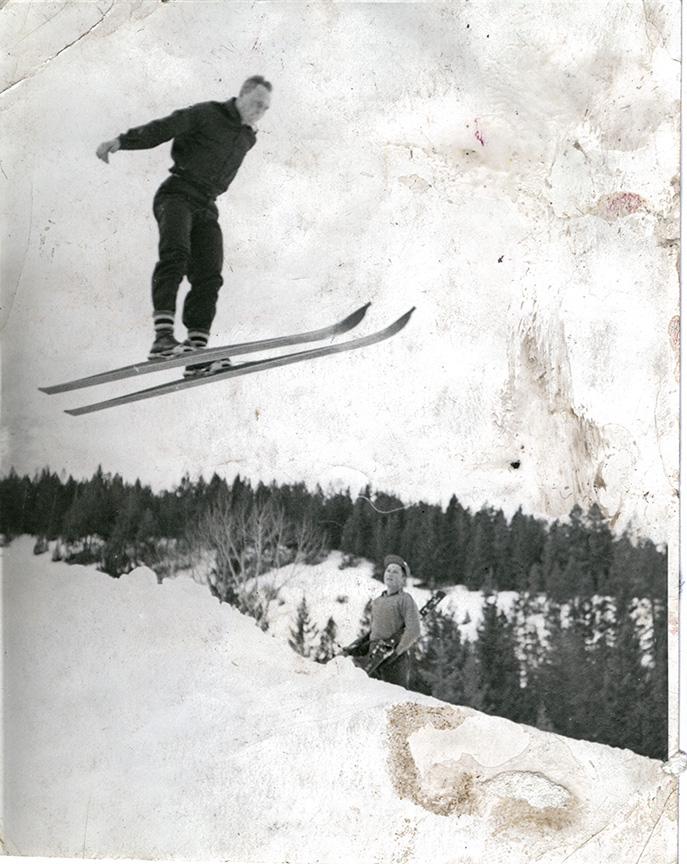

Bozeman’s original ski pioneers invented extreme, just by the fact that they skied.

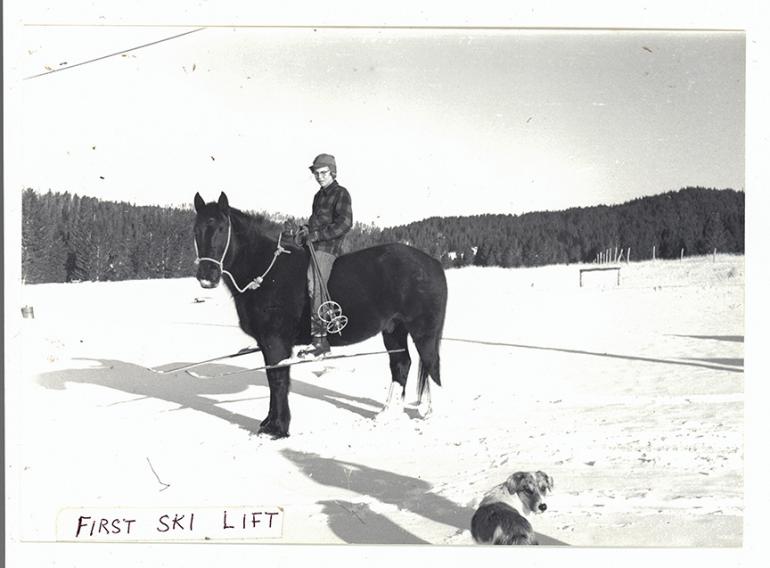

Imagine strapping on six-foot-long pine or hickory boards—“shaped” skis of the 1930s and 1940s—using leather thongs or a bear trap binding to attach the boot. The boot exterior isn’t waterproof or designed to stabilize feet going downhill at high speeds; it’s just an ordinary leather snow boot. For warmth, there are wool pants that get heavy and soaked with tumbles, and a poplin coat, big enough to accommodate some sweaters layered beneath. Make sure you get an elk in the fall; you’ll need the skins—real animal skins—for strapping underneath skis when climbing hills. Also, if you’re more interested in riding up the ski tow than down the 90-foot jump at Karst Kamp down the Gallatin Canyon, make sure you sew some extra layers onto the palms of your mittens. Hopefully by the end of the day the car-engine-powered tow, a.k.a. the “mitten shredder,” will have spared you a last layer to get home.

The effort just to get to ski hills back then suggests extremes of commitment. Take ski pioneer Lyle Olson’s account of his early-day explorations at Bridger as told to The Bozeman Daily Chronicle, January 3, 1983:

“The Bridger Road was not the smooth, oiled surface we know today, but a potholed, roller-coaster gravel road made even worse by the winter snow-storms. This, however, did not deter small groups of gung-ho skiers, who would wind their way up the road from Bozeman and park on the roadside, adjacent to the present turnoff to the Bridger ski area. In those days, after parking there still remained a long cross-country trek across streams, through thick brush and around trees to get to the base of the mountain. It was a challenge for the most aggressive skier.”

When people skied at Pine Hill in the 1930s, in the area known today as the Story Hills, some cross-country skied from town, then herring-boned up the hills, made runs until they couldn’t, then skied home. There are similar tales of skiers getting to Bear Canyon this way, though it required a nine-mile cross-country ski to get to the hill from town.

By the 1940s, Bear Canyon was the hot spot for skiing, with another homemade car-engine rope tow and a warming cabin where chicken and noodles were served. Volunteers cleared the hill of debris and made the area operational; even a twenty-five cent ride up the tow required that a skier first help pack a section of the hill. Skiing there became so popular that they had moonlight ski parties and night skiing on weeknights, lighting the slopes as best they could with flares. By the time the first rope tow was running at Bridger (known then as Bridger State Park) in the early 1950s, some skiers, like high school ski team member Sonja Lachenmaier, nearly lived at the ski hill, rivaling any of today’s crazed season pass holders:

"...never did our enthusiasm wane, even after skiing every day from Thanksgiving to April. George Ripley ran the ski tow that first year of operation. He owned an old army six-by-six with high clearance. On weekends, as spring arrived, we enthusiasts would get up at five in the morning to meet at the turnoff to Bridger Bowl at six o’clock, where George would load fifteen or twenty of us into his truck and bounce us over ruts in the frozen ground to the ski area. Here he would start the tow for our day of fun on the best corn snow of the season. By ten in the morning, bare arms and shorts abounded as we found places to stretch out in the sun. By noon, water squished around our skis, and by evening, mud and water cut deeper ruts in the road as we return...” (Cold Smoke, p.69)

Ridge runs tempted fate by skiing on or beneath heavy slabs of snow unmonitored by today’s ski patrols, and there are many skiers who witnessed the alpha side of nature at Bridger. Considering today’s avalanche equipment, asphalt, Poly-propylene, ski lifts, grooming machines, and other high-tech improvements, today’s definition of extreme seems a gift from skiers past.