Long Shot

A chance encounter with an unforgettable trio.

The mood was glum as Tom and I slogged down the trail with our headlamps on, after the fifth day in a row of utterly unsuccessful elk hunting. Maybe we should pull the plug. Call ’er quits. Throw in the towel and head to the bar. It was the same sentiment every evening after long, cold days following old elk tracks in crunchy snow. The week had been a rude awakening for two rookie hunters in search of their first Montana elk. A greasy burger sure sounded good—yet we’d more likely get to the truck, make Ramen noodles in the ever-persistent November winds, set our alarms for 5am, and crawl into a nest of blankets & sleeping bags and do it all again. Unless, that is, something unexpected were to happen.

“Horses?” a male voice interrupted as we approached the truck. A light flicked on in the parking lot.

“You have horses?” it questioned again, revealing a thick accent—eastern European of some variety.

“Uh… no horses,” Tom said.

“No horses?”

“Sorry, no horses."

“You know, like, ah, ze horses?” the man asked in broken English, gesturing to mime a horse and a rider as his form came into view.

Tom and I exchanged glances. It felt like a scene from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, only without coconuts to make the sound of clacking hooves.

“Why do you need horses?” I chimed in.

“We have elk,” the man grinned proudly. He was short and stocky, bundled head-to-toe in dark, World War II military-surplus clothes. He had a gruff face with at least a few days’ worth of stubble, but a friendly and innocent demeanor.

Sometimes paths cross without reason, and you never know what might happen unless you go along for the ride.

Through broken words and lots of pointing, we surmised that the elk wasn’t far away. It also sounded like the fellow—Jon, as he introduced himself—was accompanied by two other people, both of whom were still at the carcass.

It was already late, and Tom and I were tired from wandering aimlessly through the mountains all day. Still, we had to help. Neither of us had grown up hunting, and we’d both learned the majority of our skills through the kindness of others in the field. What goes around comes around, Tom and I both believed. Plus, our curiosity had been piqued by this strange situation.

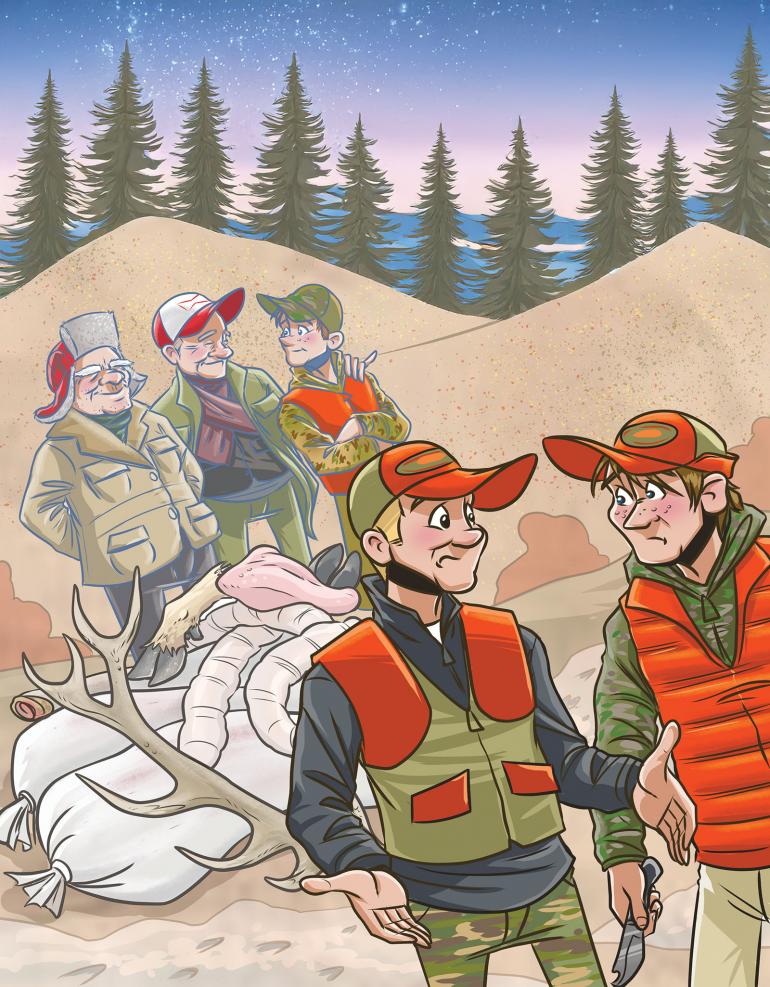

“We’ll help you,” we told Jon. We dumped the contents of our packs and followed him up a well-worn hunter trail peeling away from the parking lot. It wasn’t far—a quarter-mile at most—but sure enough, right where the meadow broke into a steep mountainous slope, there was a dead elk with two men standing over it.

The elk’s legs had been hog-tied with orange hunting vests—the flimsy kind you get from Sportsman’s Warehouse for five dollars. Tom and I shared another glance. I couldn’t see his face through his headlamp beam, but I knew his eyebrows were raised—interesting. A streak of blood and matted grass marked the slide path where the hunters had dragged the elk down the hill. The haul across the flat meadow to the truck was the final, insurmountable obstacle.

The younger of the two men bounded over. “I’m Alex,” the kid said. “My grandfather, Sergei, doesn’t speak English,” he continued, pointing to the older man, who looked up and nodded. “And my dad, Jon, well he doesn’t speak it very well either.” Alex was confident and outgoing. His English was nearly perfect, but he had the same thick accent as his father. Unlike his father’s tattered clothes, however, Alex was dressed head-to-toe in brand-new Sitka camo.

Chatting with Alex, we learned that the trio were Ukrainian immigrants who now lived in Spokane. Jon was a car salesman, and he’d bought Alex a nonresident Montana elk tag for his sixteenth birthday. Knowing nothing about hunting—other than that camo is “required”—the family had found an outfitter in West Yellowstone through an online hunting forum and paid a $2,500 deposit. But when they showed up, the outfitter didn’t exist—they’d fallen for an internet scam. Now, the Ukrainians were out over two grand and unsure about what to do next. Having already made the drive out, though, they decided to give it a shot on their own.

As we all stood back to admire the scene, Sergei mimed a cutting motion and pointed for my knife. I handed it over, curious as to what he had planned.

The shot had evidently been successful, given the dead elk at our feet. However, the Ukrainians didn’t appear to have a knife on them. Butchering the animal would’ve been the outfitter’s job, and they hadn’t thought that far ahead on their self-guided hunt.

Tom and I exchanged yet another look. What in the world were they thinking? Hunting without knives? Not letting on, though, we grabbed our blades and got to work field-dressing and quartering the animal. The trio offered help where they could, holding legs here, yanking back skin there, and reaching into the warm body cavity to pull out the tenderloins. Soon, there was a pile of clean elk quarters sitting in the snow. As we all stood back to admire the scene, Sergei mimed a cutting motion and pointed for my knife. I handed it over, curious as to what he had planned.

Knife in hand, Sergei went to work. He started with the lungs, pulling them out one by one and adding them to the pile, followed by the liver and kidneys. Then, Alex and Jon helped him pry the jaws apart so he could saw out the tongue. Finally, he attacked the ankle joints, jabbing and slicing until the hooves popped off. The “meat” pile now looked like the remnants of a sadistic ritual.

“What are you gonna do with all those?” Tom asked Sergei. The old man just looked up, smiled, and nodded.

In response to my incredulity, Sergei looked up and muttered the closest thing to English we’d heard from him all day. “Heh heh heh,” he chuckled through a thick eastern-European drawl. “Sny-pear.”

With exhaustion from the day setting in, Tom and I loaded up our packs with all four quarters and headed back to the parking lot. Sergei walked with a limp at a painfully slow gait, so Alex stayed behind to help his grandfather navigate the trail. Back at the vehicles, Jon thanked us for the help.

“Meet at bar?” he said, swigging a beer in pantomime.

I nodded, picking up my own imaginary bottle and throwing it back. Done deal.

Soon, the five of us had gathered around a table at the nearby watering hole with shots of vodka all around. Alex and Jon took turns detailing the story of the afternoon. “It walked out of the trees at the very end of the day,” Alex recounted.

“He take de shot off pack,” Jon added. Sergei pretended to line up a rifle across the table. A huge smile adorned his face.

“How far was the shot?” Tom asked.

“Maybe 800 yards?” Alex estimated. Tom nearly choked on his burger.

“Where did you aim?” he followed up after a hacking fit, his face in disbelief.

“About ten feet over its back,” said Alex, matter-of-factly. He nonchalantly resumed eating his burger.

Once again, Tom and I exchanged bewildered glances. It couldn’t be. There’s no way! Trying to parse out what had really happened, we looked to Jon and Sergei, whose grins did nothing but reinforce the validity of Alex’s marksmanship.

I cocked my head in incredulity. In response, Sergei looked up and muttered the closest thing to English we’d heard from him all day. “Heh heh heh,” he chuckled through a thick eastern-European drawl. “Sny-pear.”

Jon sipped his vodka and responded in agreement. “Da. My boy is sniper!”

Feeling the alcohol taking hold, Tom and I agreed it was time to go before things got out of hand. We exchanged contact info with Jon and said our goodbyes.

Neither Tom or I had grown up hunting, and we’d both learned the majority of our skills through the kindness of others in the field. We believed that goes around comes around.

Driving down a desolate dirt road a few minutes later, Tom and I couldn’t help but laugh at the absurdity of the whole evening. But that’s the beauty of serendipity. Sometimes paths cross without reason, and you never know what might happen unless you go along for the ride.

Like a wild one-night stand, the evening was one that nobody will forget. Tom and I would soon head back to Bozeman to tell the story of the crazy Ukrainians, and they would return to Spokane to tell the story of the crazy Montanans. The two tales will likely never come ’round full circle, but perhaps one day they will. It’s impossible to know for sure. Suffice it to say: what goes around comes around.