The Ultimate Attractor

Hidden treasures found on secret streams.

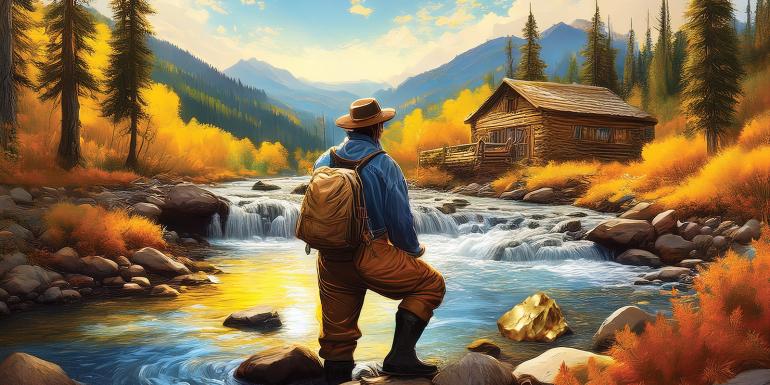

The deepest eddies in the stream paralleling the county highway supported several trout and an abundance of mountain whitefish. The latter usually accepted any well-presented, small nymphs. Occasionally, I noticed fly fishermen balanced on the riprap slope, tirelessly throwing small mends into their lines to match the swirling current. This was not my type of fly fishing. Still, I understood the allure of fishing a small stream tantalizingly close to the Madison, unburdened by the larger river’s fishing pressure.

My preferred crossing spot required a modest hike and an easy climb over a low, barbed-wire fence. Once I was on the other bank, I followed a poorly defined trail upstream through rabbitbrush, sage, wheatgrass, and wild rye. The small trout in the rapids and shallow pools willingly rose for a Purple Daze, yellow humpy, or mini Chubby Chernobyl.

On an overcast day in late October, when the approach of winter and the end to another fishing season was imminent, I attached the attractor pattern to the hook tender and strayed further afield. The route grew rockier beyond the first hill, and for a moment, I lost sight of flowing water. When the stream reappeared, small boulders clogged the narrow riverbed.

Knowing the descent would be less strenuous, I kept climbing. Soon the trail flattened and morphed into a glorified deer path.

Knee-high vegetation yielded to sparce deciduous trees and scraggly bushes bearing a few clumps of late-season dark berries. The hair on my neck pricked; this was prime bear country. I paused at a pool below a small waterfall and landed three feisty rainbows on as many casts. Slipping the last fish back into the water, I spotted a low pile of dirt-covered boards, partially concealed by the hillside foliage. A closer inspection revealed a crushed section of tar paper beneath the rotten lumber.

I began painstakingly surveying the ground around me, broadening my search area until it covered the entirety of the gravel mounds.

I set out to explore the surrounding woods and eventually located an abandoned cabin. Tree limbs and wild rosebushes covered what little remained of the walls. I couldn’t tell if the cabin was 50 or a 150 years old, but I admired the hardiness of anyone willing to brave a Montana winter surrounded with such minimal protection.

While I initially believed it was a hunter’s cabin, a series of low, gravel mounds further upstream suggested its residents had been placer mining on a small scale.

On my next visit in early November, the wild roses had shed their leaves and a solid layer of snow blanketed the vegetation surrounding the cabin. The dwelling seemed even more spartan than I recalled.

I drifted a Royal Wulff through the riffles and admired the acrobatic feats of the hooked trout. So far, I hadn’t found any discarded fishing line, trash, or other signs of human activity. This upper part of the stream was starting to feel like my private refuge.

I sat on one of the gravel mounds in a patch of weak sunlight, extended my legs, and ate my lunch. As I did so, my right foot dug into the rocks, dislodging an oblong, mustard-colored pebble about the size of a 50-cent piece. Narrow ribbons of white mineral crisscrossed the rock’s slightly rounded surface. On a whim, I dragged the Royal Wulff’s hook point across the darkest part of the pebble and ran my fingernail through the resulting deep furrow. As I repeated the process, achieving same result, all thoughts of food and fishing vanished.

The hair on my neck pricked; this was prime bear country. I paused at a pool below a small waterfall and landed three feisty rainbows on as many casts.

I began painstakingly surveying the ground around me, broadening my search area until it covered the entirety of the gravel mounds. I even waded into the stream and turned over some of the smaller boulders. While they muddied the otherwise clear water, my efforts failed to reveal any additional mustard-colored pebbles.

Disappointed and slightly chagrined by my mistreatment of the small stream, I stared at the nugget in my palm. I realized that my discovery had the potential to completely alter this tiny bit of paradise. Conflicted, I began pacing back and forth beside the water and considered a range of options, ultimately discarding all but one.

With my mind set, I slipped the pebble into my pocket, snapped it shut, took a lingering look around at my surroundings, and regained the deer path. I stopped once during the descent, at the tumbledown cabin that now seemed like such an integral part of the forest. Retrieving the pebble from my pocket, I held it up in my outstretched palm, nodding at the dilapidated structure.

The following year I sold the pebble to a collector.

I still visit my favorite stream, especially when the Madison is crowded. So far, I’ve resisted the temptation to venture beyond that first rise, but I often pause, gaze upstream, and wonder if the cabin still stands, and whether or not erosion has exposed additional, mustard-colored stones.

This is a work of fiction, an embellishment based on the author’s experiences fishing the Madison River and its tributaries.