Every Last Drop

Chasing cutthroats and other backcountry bounty in the heart of Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness.

The straps on my backpack cut deeper into my shoulders with every step. For a while it felt like nothing more than the general aches and pains of a heavy load, but it’s worsened in the last hour. I might be bleeding. My feet aren’t faring much better. The open flap on my left heel has stained my socks red all the way up the calf.

But I can’t be worse off than Logan. Last night, we camped in a wind-licked fir stand whose only trees over 20 feet were old branchless snags. In a tired stupor, Logan tied his shoe to one end of our bear hang and tossed it directly over a greyback. He made a great shot, but soon regretted the move as the cord slipped into a crack and became firmly lodged in the belly of the tree, his shoe dangling near the top. Despite our group’s best efforts, it remained out of reach. Luckily, he’d packed a set of Crocs with him for camp shoes. Now, he’s spent an entire day schlepping a pack loaded with camping gear, a week’s worth of food, packraft, PFD, and fishing tackle 11 miles and 3,200 vertical feet with his right foot protected only by a rubber sandal.

The first three casts all draw strikes before I can even strip. Not worried about disturbing anyone else in the canyon, I bellow a celebratory howl into the empty wilderness.

Evening’s arrival is a welcome distraction for both of us. The air is golden. Aging sunlight glows off fields of native bunchgrass and casts warm air through a canopy of gigantic ponderosa pine. Old growth, spaced 200 feet from one another: signals that we are in a landscape shaped by fire. Though we still have a couple miles to go, the scene provides some reinvigoration. Until we hit the bear tracks, that is.

“That looks like it’s heading right where we’re gonna camp,” Ashley says. Morgan agrees, suggesting we set up camp right where we are.

The four of us look at each other the same way, each wishing another would make the call. Finally, after a long silence, Logan perks up. “We gotta make it to that river.”

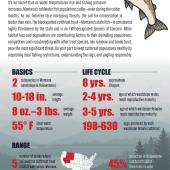

That river is the South Fork of the Flathead, a pristine stretch of Montana’s most remote, unspoiled, healthy water. It flows nearly 100 miles through the heart of the Bob Marshall Wilderness and is a major sanctuary for westlope cutthroat trout, which we intend to put on the menu. We’ve been hiking for five days straight, covering 55 miles and two significant mountain passes. Tomorrow is our scheduled layover. Finally, it’ll be time to fish.

But… the bear. “Right now, it’s just a track,” I chime in optimistically. “I say we keep going until it doesn’t make sense anymore.” Everyone seems on board. I unfold my pocketknife, lay it beside the track, and take a photo. Then we carry on.

Daylight has all but fizzled by the time we reach the South Fork. We’re awarded one short glimpse of its serpentine figure before darkness drops like a hammer on the whole valley. Dinner is cooked on a rock bar on the eastern bank. I barely finish my meal before passing out in a dreamless sleep.

Morning is slow. Not because we’re behind schedule, just that this is the first time in the last week that we have the opportunity to linger. After a casual 10am breakfast and three cups of coffee, we uncase our rods and walk to the water’s edge. Seeing it for the first time in the light sparks awe in all of us. It’s aquamarine and translucent all the way to the bottom, a sweeping band 150 feet wide bending twice in our half-mile vantage. This is no mountain stream that cascades down steep side drainages in busy fits and furies. This is a river.

Below us, a glassy tongue feeds into a slow mid-channel run with pockets on both sides, emptying into a deep pool at the bottom before appearing to repeat a couple hundred yards downstream. “I take the top and you hit the bottom?” I propose to Logan. “Let’s do it!” he yips, his smile nearly splitting his cheeks.

Evening’s arrival is a welcome distraction for both of us. The air is golden. Aging sunlight glows off fields of native bunchgrass and casts warm air through a canopy of gigantic ponderosa pine.

I tie on a caddis and let it work the eddy line. My brown-and-white replica plops on a seam and dances briefly in the current before being gobbled up by a hungry cutthroat. The first three casts all draw strikes before I can even strip. Not worried about disturbing anyone else in the canyon, I bellow a celebratory howl into the empty wilderness. The girls, reading books on the bank behind me, laugh at my antics. Logan returns with a roar of his own, holding up a cutty to the sunlight before resubmerging it and letting it go.

The action continues. I tie on a PMD, an Adams, a Purple Haze. It doesn’t matter, it’s one after the other all afternoon. Nothing huge, but we land plenty of fish in the 12- to 14-inch range, which offer more than enough fight to keep us entertained. When the heat of the day arrives, we lean the rods against a granddaddy ponderosa and dive headfirst into a pool that winds like a horseshoe around the bank. We body-float the lazy section until the river gets too shallow. Then, we clamber up the bank, hike back up, dry off in the sun, and jump back in.

By evening, Logan and I each have three fish gutted and skewered on willow sticks. With daily limits notched, we hike back to camp and fetch the remaining supplies for supper. It’s a generous coating of butter and seasonings before we lay our catch in a pan over hot coals. Served with rice and veggies, it’s our best backcountry meal yet. On these evenings, when the day’s bounty has far exceeded any and all expectations, it’s hard to go to sleep. We stay at the fire longer than previous nights. Even when we’re too tired to talk, more wood gets piled on—drinking in every drop of available juice, we refuse to let our circle of warmth die. Silently, the Milky Way comes to life in a blaze of galactic grandeur, and the sky full of burning stars and dying light somehow makes our insignificance feel that much sweeter.

This is no mountain stream that cascades down steep side drainages in busy fits and furies. This is a river.

Two years later, I find myself 35 miles north on another tributary of the Flathead, the Middle Fork. Ash is with me again, as is my cousin Trenton. We stand at the edge of a giant pasture and watch as a Super Cub buzzes the treetops, sets down in the field, and comes to a stop. This is Schafer Meadows, the only active airstrip in the Bob. Constructed in 1933, the landing zone was grandfathered into the Wilderness Act. Maintaining it involves primitive practices such as horses and mules dragging graters.

While many people opt to access this faraway haunt by means of aircraft, we have chosen to walk here via a side drainage 17 miles downstream. We took a day and a half to get here, spending our mornings and evenings fishing the slack water. Now, we plan to inflate packrafts and paddle out two days and close to 30 miles to the confluence with the Main Flathead near West Glacier. There will be plenty of time to wet a line, but our minds are focused on the river between the pools.

The Middle Fork of the Flathead is a prolific fishery, much like its sister to the south. But unlike the calmer South Fork, the Middle is punctuated with sets of Class IV rapids, two of which are known to be consequential. Even in the month of July, when waters are low and more forgiving, we find ourselves on edge for what lies downstream.

Groups of cutthroat swim effortlessly below us and we observe them in a trance-like state. We drift in silence until a leviathan of a bull trout emerges from under a rock and swallows one of his smaller cousins.

After a quick tour of Schafer and a visit with the ranger who lives there, we hike a mile downstream to where we’ll camp for the night and put in the following morning. We do our best to push our reservations and nerves aside to what is tomorrow’s problem. For there are fish to catch.

The evening is spent meandering side channels and testing out different flies. There isn’t a prominent hatch going on, but many mid-sized cutties take the dry anyway. It’s a beginner’s paradise and Trenton and I, both weekend-warrior anglers, revel in this fact well after the sun goes down.

The next morning is all business. We pack with a purpose and get on the water in a timely manner. The three of us are all capable boaters, but being on a self-supported packraft trip is different than running any old roadside rapid. The expedition component ramps up the risk meter in ways that are both thrilling and unnerving. It takes less than an hour to reach the first section marked on our map. Known as Three Forks, this series is a two-mile stretch of intermittent rocky drops and maneuvers. We stop and scout a couple, but most of it is read-and-run. Reaching the end of the set allows us to take a breath—we won’t have to worry about the true crux of the river––Spruce Park––’til tomorrow.

Having taken my guard down, I follow Trenton into the next canyon nonchalantly. In fact, I daydream of having a cold one. Suddenly, the walls narrow and the roar of whitewater increases. Soon, it becomes too loud to yell over the crashing waves. Two standing boulders create three passages to choose from and I watch Trenton take the middle slot and disappear as gravity grabs him over the horizon line in an instant. It looks like a big drop, something that may tip me, so I opt for the more constricted channel on the right. When I reach the edge, I realize I have nowhere near the speed I need to clear the plunge and take one last worthless stroke before drifting into a slow fall that results in me upside-down in the pool below. I keep a hand on the raft and I’m back in my boat in 10 seconds. As I clamber back aboard, Trenton paddles up to rub it in. “Das boot!” he cackles, indicating that I have just earned myself a beer from my shoe.

Our final day opens to bluebird skies. Trenton is up before sunrise, per usual, and is trying his luck in the house-sized pool we camped near. “They’re everywhere in here!” he cries, as Ash and I lounge in our bags. “I can see at least 30 of ’em!” I boil water, pour each of us a cup of coffee, and join him. Indeed, he’s right, schools of fish dart back and forth alongside a cliff wall on the opposing bank, including a lunker that looks like it might push 20 inches.

I slurp down my joe and prepare my rig. “Sucker popped off!” Trenton hisses, slapping his rod down on the water. “Go try your luck elsewhere, bud,” I kid him. “Don’t you know that patience is a virtue?” He steps aside and lets me have a crack. I work the hole for half an hour, reeling in half a dozen small trout, but the big one doesn’t bite. Knowing it’s our last day, we take our time in the morning sun before packing up and rigging our boats for the remaining whitewater.

Silently, the Milky Way comes to life in a blaze of galactic grandeur, and the sky full of burning stars and dying light somehow makes our insignificance feel that much sweeter.

Spruce Park proves to be fierce and beautiful; a smattering of boulders and constrictions make for some of the finest rapids we’ve ever paddled. Fortunately, we pass through uneventfully and are soon in the final few miles of flatwater. I put in fewer and fewer strokes, prolonging our float a couple seconds at a time, drinking in every last drop. We reach a section where the banks once again tighten up and the river deepens. It’s gin-clear, and we can see all the way to the bottom, which we estimate at around 20 feet. Groups of cutthroat swim effortlessly below us and we observe them in a trance-like state. We drift in silence until a leviathan of a bull trout emerges from under a rock and swallows one of his smaller cousins.

“Did you see that?!”

“Good Lord!”

“Unbelievable!”

We pull the boats ashore and scramble up a rock wall to get a view from above. The monster shows himself once more. Well over two feet, it’s a goliath compared to the other trout he swims with. It’s illegal to target bull trout in the Middle Fork, but we are plenty content watching. The darkish beast snakes his way along the cliffside, never revealing himself in the sun, and vanishes around the corner upstream.

The three of us remain hysterical for the last few bends, recounting the trip and planting seeds for the next one. I’m sunburned and thirsty when we reach the takeout. We schlep the boats up to Trenton’s truck where he drops the tailgate and pops open a cooler. I’m suddenly grateful he thought ahead five days ago, packing it full of ice. He tosses me a Coors with a smirk. “All right, buddy, let’s see it. Time for your booty beer.”

Flathead Considerations

by Corey Hocket

Things to consider when taking a trip up north.

Hiring a guide. Many outfitters run trips on both the South and Middle Forks and can pack in an assortment of gear via stock or plane.

Water levels. Too high can result in poor fishing (and gnarly rapids) while too low can end in dragging boats for long periods of time. Generally, peak runoff occurs in early June. For current and historic trends, check the Hungry Horse gauge for the South Fork and the one near West Glacier for the Middle.

Grizzly bears. Healthy numbers exist throughout all the Bob Marshall and Great Bear Wilderness Areas. Plan accordingly.

Bull trout. Are listed as a threatened species. Targeting them is allowed only on Lake Koocanusa, Hungry Horse Reservoir, and certain sections of the South Fork. You must choose the exact area you wish to fish (during certain times of year) and are required to have a Bull Trout Catch Card in possession at all times. Learn more at fwp.mt.gov/fish/regulations/bull-trout.

Meadow Creek Gorge. While this article illustrates the moderate nature of the South Fork, bear in mind that this does not include Meadow Creek Gorge. Plan your trip to take out above the entrance as it should be run by expert boaters in small crafts only.

This piece originally appeared in the Spring/Summer digital edition of Montana Fly Fishing Magazine. You can check out the article here.