Follow the Fear

The mountains are full of danger; prepare for risk and reap the rewards.

It’s late in the evening when I reach the trailhead, maybe two more hours of light. One car with out-of-state plates sits in the lot. Usually, I expect overflow parking at this spot, and that’s why I’ve waited. The trail is popular for good reason, and I enjoy riding it as much as the next guy, but I don’t love crowds.

Tonight, however, I’ve played my cards right. Climbing switchback after switchback, I’m alone—just me and the horseflies and the setting sun. Or so I think.

After what feels like the six-hundredth switchback, I hear music. It’s muffled and coming from above. I stop and look up in an effort to identify the source. Then someone pops out of the brush not more than 50 feet in front of me.

“I saw a bear,” she says, her voice shaking a bit as she tries unsuccessfully to keep her dog close. He wanders over and licks my sweaty sock.

“Oh,” I say, not sure how to proceed. “Was it a big guy?”

“No, pretty small. He ran into the bushes a few minutes ago.”

“Cool. I’m sure he’s well on his way by now. Do you have spray?”

“No. I’m just waiting a few minutes to give him some space.”

“Right on. Enjoy the rest of your hike.” And I’m off, thinking nothing of the interaction, except I wish she’d turn that music down.

I pedal on, whistling as I go, making my way above the worst of the climb and into a now-dead wildflower meadow. The grass is brown and wilting, and combined with the fading light, a reminder that darkness is approaching and I’d better turn around.

Rolling downhill now, my focus is specific: don’t crash. The trail is loose after another hot, dry summer, and the pebbles act like ball bearings. Drifting around a turn, I’m struck by a familiar sound: music. The girl is right where I left her, still waiting out the bear.

“Taking your time, I see.”

“Yeah.” She’s sheepish, but I take that as shyness and with a friendly salutation I’m off again.

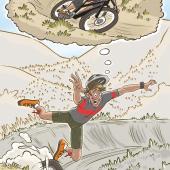

A bit further down the trail, I realize what’s really going on: this girl is terrified. She’s seen a bear, possibly her first, and she can’t bring herself to go on. Fear has gotten the best of her. As I’m having this realization, two men walk up the trail, one with bear spray in hand and another with a shotgun slung over his shoulder.

“Have you seen a girl on trail? We’re here to rescue her.”

What? Instead of seeking the advice of another person on the trail, she’s called her friends to save her. Which is fine, although I wish they hadn’t shown up with a gun—was their plan to shoot the bear? So many reasons for bewilderment. But what I’m most struck by is the fear.

At one time, I was that girl—not quite as paralyzed, but equally afraid. I didn’t know what to expect in the woods, and that ignorance manifested itself as fear.

I rode Moser with bear spray in hand, slapping my thighs to make noise, whistling to an imaginary dog when I ran into people, as self-conscious as the girl. I didn’t hike at all in or near Yellowstone Park without a group. I avoided the deep woods in fall, as bear-human interactions spike this time of year. And I avoided anything approaching avalanche terrain, because I couldn’t think of a worse way to die.

When I was new here, I looked at the dangers of the mountains as insurmountable obstacles. Over time, however, I realized something: while the danger doesn’t go away, it can be managed. Risk is inherent in the mountains—but injury is optional.

In many ways, I moved to Montana for the risk in these woods. I wanted to be a little closer to struggle, even if that struggle was something as manufactured as a tough mountain-bike climb or a long ski approach. Like many others, I failed to calculate the actual struggle, like animals and avalanches.

Instead of packing it up and heading back home, bit by bit, I learned the ropes. Preparation didn’t eliminate danger, but it stacked the odds in my favor. In the case of the bear-scared girl, if she’d had spray, been hiking with friends, known what kind of bear she saw, or hadn’t decided to hike right before dark, she’d have realized the small amount of actual danger she was in. In her case, a sprained ankle would have been a worse outcome than a bear sighting.

But, now she’s had that experience. While fear paralyzed her once, odds are she’ll be less afraid the next time she sees a bear. Perhaps she’ll look up some information on bear behavior, or proper human behavior in the presence of bears. She’ll most definitely buy some pepper spray and (hopefully) practice with it. With any luck, she’ll look at a map and understand where she’s going in relation to bear territory.

Point being, she should learn from her experience and turn fear into preparation. Or else, what’s the point? Being scared in the woods isn’t fun.

The idea is to overcome—fear may continue to follow you, but preparation should lead the way. That way, you keep the odds in your favor. Plus, bear sightings become a whole lot cooler.