A Big Day in This House of Sky

How one man’s exploration of Montana’s hardscrabble past revealed far more than what he bargained for.

I glance higher for some hint of the weather, and the square of air broadens to become the blue expanse over Montana range, and so vast and vaunting that it rears from the foundation line of the plains horizon to form the walls and roof of all of life’s experiences that my younger self could imagine, a single great house of sky. —Ivan Doig from This House of Sky

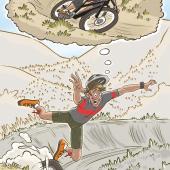

Ever wake up on a weekend morning in early spring—sun shining, birds singing—and you just know you have to do something BIG? But what? Skis are back in storage, trails are too muddy to responsibly ride, and you’ve already bagged the few lengthy snow-free hikes like the Yellowstone River Trail. But it’s been a stressful week at work, not to mention a long, cold winter. Something epic is in order.

That was me one April day. Though long ago, it remains indelibly etched in my mind. I distinctly remember glancing at the nightstand next to my bed and knowing immediately what I was going to do. There lay a copy of This House of Sky, Ivan Doig’s magnificent memoir of growing up on a hardscrabble Montana ranch. I thought, “How about a bike ride through the rural countryside he so eloquently described in his book?”

And I had just the bike to do it: a 1987 CyclePro Arroyo. At the time, it was marketed as a mountain bike. Compared to today’s high-tech models, it was like a Model T, and I seldom actually used it for mountain biking. But on gravel and dirt roads, it rocked.

I decided to focus my ride on the upper Shields River Valley where Doig lived for a time. I pulled out my Montana Gazetteer to plot my route. Starting in Ringling, I would string together gravel roads and do a wide loop around that faded but storied community.

It was a bluebird day, almost warm. Most importantly, it wasn’t windy, which is a rarity in these parts. I threw a light jacket in my pack, a water bottle, some snacks, and while I knew I wouldn’t need it, a headlamp. Then I tossed the pack and bike in the back of my pickup, and headed north on Hwy. 89.

Ringling lay on the land, as the imprint of what had been a town, like the yellowed outline on grass after a tent has been taken down. When the roadbed of the Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad was diked through the site early in the century, a community snappily built up around the depot. But before the end of 1920s, many of the businesses had burned in a single wild night of flame.

I parked in front of one of the few remaining buildings, the Ringling Bar, which seemed like the perfect place for a post-ride burger and beer, then set off. I love that rolling countryside with its sage-covered hills, amber waves of grain, and the occasional lonely abandoned homestead. In the distance, spooky pronghorn, still shell-shocked from the previous hunting season, bolted in the opposite direction. The Pleistocene call of recently arrived sandhill cranes occasionally broke the silence.

I’m not exactly sure how far I rode that morning, but by early afternoon I was back at my truck. It had been a good day, at least 40 miles, but not what I considered a BIG day. So, I pulled out my dog-eared Gazetteer to see if I could add a few miles and take full advantage of the lovely spring weather.

In my case, this naïve, if not downright ridiculous, thinking was where the proverbial cart began to go off the rails.

Looking at the map I thought, “It’s highway riding, but White Sulphur Springs is only about 20 miles away.” In those days, highway traffic in those parts was light. To White Sulphur and back would indeed make it an epic ride. And that town—Doig’s birthplace—played heavily into his narrative. So off I went, savoring the iconic ranching landscape in the foreground, the Castle Mountains to my right, the eastern end of the Big Belts to my left. I rolled into White Sulphur around three.

Sited where the northern edge of the valley began to rumple into low hills by an early-day entrepreneur who dreamed of getting rich from the puddles of mineral water bubbling up there, and didn’t—White Sulphur somehow had stretched itself awkwardly along the design of a very wide T. This gave the town an odd, strung-out pattern of life, as if parts of the community had been pinned along a clothesline. But it also meant that there was an openness to town, plenty of space to see on to the next thing that might interest you.

Now I’m definitely not what you would call an “extreme” outdoor athlete. Far from it. But on occasion, and generally not by design, I’ve had some extreme outdoor adventures—the ones where you finally make it back to your vehicle and the first thing you do is call home to tell your family not to call search & rescue. But on this particular day, I felt compelled to once again consult the Gazetteer to see if there might be a route back to my truck that didn’t retrace already-covered ground. About six miles east of the town, a Forest Service road took off from Hwy. 12, climbed up and over the Castle Mountains, and eventually hit Hwy. 294, which ends near Ringling.

The Castle Mountains poke great turrets of stone out of the black-green forests. From below in the valley, the spires look as if they had been engineered prettily up from the forest floor whenever someone took the notion, an entire mountain range of castle-builder’s whims.

In retrospect, the decision to take a shot at completing this loop was nothing short of insane. But at that age, on that day, it seemed, well, at least plausible. I had hiked a bit in the Castles. However, I had never driven that road all the way through, though once I had been on the other side of the mountains while visiting the ghost town of Castle. According to the Forest Service sign, Castle Town was 18 miles away. While that seemed a little daunting, I thought all I needed to do was reach the summit. From there it would be downhill all the way back to Ringling.

Just as investigators can identify exactly where forest fires started, the same is often true for the genesis of an outdoor misadventure. In my case, this naïve, if not downright ridiculous, thinking was where the proverbial cart began to go off the rails.

The pedal up and over the range started out okay. The narrow dirt and gravel road was fairly dry with some water-filled potholes, but perfectly ridable. After a while though, I started to notice small patches of snow appearing off in the woods. The higher I climbed, the larger they got. Pretty soon, they spilled onto the road. I was concerned, but thought that I must be close to the summit. I pressed on.

To my dismay, the snow soon crossed my path. It wasn’t so deep that I couldn’t ride through it, but I knew it wasn’t a good situation. This was pre-GPS. I had no idea exactly how far I was from the top, both in distance and elevation. In a short while, there was too much snow and I bogged down. And the sun—yes, that friendly warm glowing ball that had awakened me so many hours before—was now buried deep behind the mountains to the west.

I had to make a decision: swallow my pride and ask for refuge, or continue on and perhaps become a sad story in the Bozeman Daily Chronicle.

Gut-check time. I threw on my jacket, slugged down my last gulps of water, took the final bite of a Snickers, hoisted my bike, and started trudging through the snow. I was hoping—no, make that praying—that I would soon summit and that long sweet downhill stretch would roll out before me.

I’m not a quitter, but I swear I was only a heartbeat away from throwing in the towel when the road started to slant downhill. Pretty soon, the snow was shallow enough that I could remount. Then the snow retreated altogether and it was smooth sailing. I was home free! Or was I? God, it was getting cold and dark. I pulled out that headlamp I thought I would never need and continued barreling down the mountain with only a small cone of light illuminating rocks and potholes.

Though feeling a bit of relief, I knew something wasn’t right. I began shivering uncontrollably. Exhaustion was overwhelming the adrenaline rush from my summit. My thought processes seemed… fuzzy. But not so fuzzy that I didn’t realize I was becoming hypothermic.

Suddenly, off in the distance, I saw a lone light piercing the inky darkness—incentive enough to persevere. Pretty soon, I was standing in front of a solitary ranch house in the middle of what seemed like nowhere. I had to make a decision: swallow my pride and ask for refuge, or continue on and perhaps become a sad story in the Bozeman Daily Chronicle. You know, the kind that when you read it you say to yourself, “What on Earth was that guy thinking?”

I knocked. A young woman, wide-eyed at what the cat dragged in, opened the door. In a shaky voice, I profusely apologized and asked if I could enter for just a moment to warm up. She disappeared, and an older man, clearly the patriarch of the household, stood in front of me. I knew I was a pathetic sight, but again explained my predicament. “C’mon in,” he said. “Do you want some whiskey?”

The house was warm and filled with the comforting smells of Sunday-night dinner, though that made me feel even more like an idiot. But the gentleman graciously assured me that I had not been the first lost soul to appear at their door. Apparently, this sort of surprise intrusion occurred somewhat frequently, especially during hunting season.

Long story short, they fed me, asked about my life, and tried to not make me feel too guilty about barging in on them. Ironically, at this point in my career, I was working for a conservation group that was sometimes at loggerheads with the ranching community. Public-land grazing was the environmental issue du jour. And while I personally wasn’t focused on that contentious topic, my organization was. In retrospect, I perhaps disingenuously danced around the conversation of what I did for work. It was not the right time for a debate.

At the end of the meal, the father asked his son to drive me back to Ringling. I was shocked to learn how far I still had to go. I never would have made it. During the drive home from Ringling, I realized that these folks might well have saved my life.

The most lasting impact was a significant change in how I view our rural neighbors.

The next day, I marched down to the La Chatelaine Chocolate Shop and purchased a box of goodies, then a thank-you card from Vargo’s, and mailed the package to that Castle Road ranch family. It had to be in the mail that day—the least I could do to show my appreciation.

Spaced where I am, past having been young but not quite yet middle-aged, the odds of life and death still loomed quite far from my usual thoughts. Yet this much has been brought home to me fully: the sensation of having been hurled out of deepest hazard. The links are made instantly by memory.

The experience had a profound effect on me. Yes, I still occasionally bite off more than I can chew during my outdoor excursions. But I’m less apt to trundle on when conditions turn sketchy. Just being outside is now the preeminent goal. Summiting, completing a loop, arriving at a specific destination—those are just icing on the cake.

However, the most lasting impact was a significant change in how I view our rural neighbors. In This House of Sky, Doig lovingly describes the pluck and hard-earned resilience of rural Montanans—not to mention their allegiance to family and friends. All are admirable traits in my humble opinion. But being a townie, and in these contentious times, it’s all too easy to stereotype “them” as being so different from “us.” I no longer believe that to be true. We’re all in this together. I have also realized that our rural playground is their place of work. They have more important things to do than deal with the silly predicaments that we city folk often find ourselves in while exploring the hinterlands. I now try mightily to avoid such embarrassing circumstances.

My desire to evoke the writings of Ivan Doig by traversing the rural landscapes described in his novel went a step further. I actually, kinda, sorta, got a taste of the challenges posed by this wild and wonderful landscape on the people who live there; the challenges that shaped the character of Ivan, his family, and childhood friends. And I realized that those unique human qualities remain alive and well in the folks who are living today under Montana’s ever wondrous house of sky. It was a life-changing experience salvaged from a near disastrous day—and a lesson I won’t soon forget.