Who's Got Your Back?

In wild spring whitewater, knowing your party’s capabilities is of utmost importance.

Climbing onto an enormous, polished boulder, six brave souls look deep into the heart of a throbbing maelstrom. For most, high brows and wide eyes gaze up and down this ferocious display of hydraulic force before a quick headshake and humble sigh deem a portage necessary. Yet two paddlers remain atop the monolith, their hands knifing through the air while low voices and steady nerves carve out the possibilities.

Boof hard left off the center pourover, hit the slide dead center at two o’clock, land on a left brace, ride the pile high, catch the main flow, dodge the pin rock, and get on the train…

The decision is made. Both boaters will run the drop simultaneously, 75 feet separating them. Two evenly-spaced crewmembers take positions on the high banks, throwbags at the ready. Another seeks the perfect angle to capture the moment on film while the fourth picks his way to the short, calm pool at the bottom. Finally, from high above, the cameraman surveys the scene and gives a thumbs-up followed by a whirly bird, stirring into motion the surreal chain of irreversible events that is the lifeblood of the serious whitewater kayaker.

The guttural “whomp” of a well-timed boof (i.e., cleanly landing a drop) is greeted with joyous cheers from the shore while the camera’s shutter keeps time with the raspy baritone of the first kayak grinding down the long, low-angle slide and into the feathers of the aerated pillow below. Moments later, the kayak is skirting around the dragon’s tooth and triumphantly riding out the sleepy haystacks and swirling currents at the rapids’ end.

The rumbling of the second boat careening down the slide snaps the safety crew back to attention. The sickening sound of a paddle blade dragging over the granite stands hairs on end as all watch a good friend hit the churning pile sideways, leaning upstream. He is buried deep in the froth. Gone from sight. Each moment is an eternity, until finally his boat surfaces upside-down in the main current some 30 feet below his entrance point. The roll is almost instantaneous, but almost is not good enough on this drop. The kayak is flushed toward the sharp stone in the center of the channel. There is no time. The boat is broached, and though the kayaker finds a firm grip on the jagged, upstream-pointing rock, the kayak is slowly being pushed under the surface.

You don’t learn safety skills for your own benefit. You learn them for the benefit of your partners.

A throw bag is launched from shore but falls a full ten feet short and is immediately whisked downstream by the powerful current. A second one arcs through the air, stops violently in midflight, and drops well short of the mark. Struggling against the relentless current, the pinned kayaker’s mind is racing. He is in a fight for his life. Unable to extricate himself, he is now forced to depend completely on the other five members of his group to save him. It is at this terrible moment that he realizes how precious little he knows about the group’s rescue skills, about the equipment they are carrying, and about their ability to act quickly and effectively in a high-pressure situation.

Kayaking has seen a dramatic increase in popularity over the last couple decades. Once exclusively the domain of the lunatic fringe, kayaks are now commonplace props for an advertising industry hell-bent on associating with anything “X-treme.” From SUVs to STDs, whitewater thrills are now household concepts. Coupled with the unprecedented advances in boat design and equipment, more and more people are drawn to the sport each year at unheard-of rates. It is not uncommon for young, athletic boaters to be running Class V rivers routinely in a matter of two or three paddling seasons.

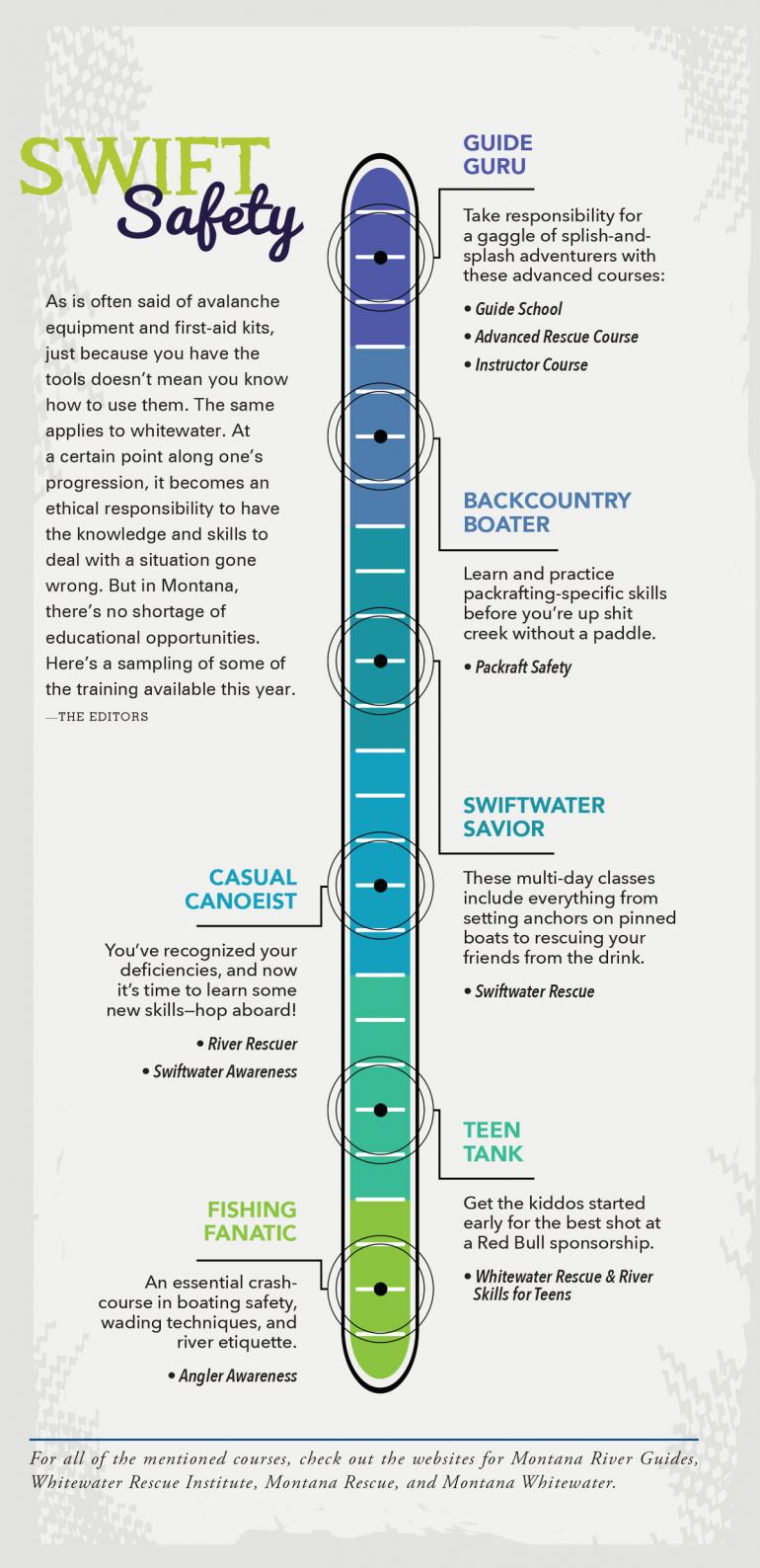

Unfortunately, it is a rare paddler whose rescue skills will match the pace of rapidly advancing technical abilities. All too often, kayakers exploring steep tributaries in remote mountain settings not only lack the skills necessary to set up strong safety systems on consequential drops, but they also lack a working knowledge of the tools and techniques required to rescue paddlers and equipment when things go awry.

Many groups, like the one above, rely heavily on one or two seasoned veterans whose experience and knowledge are invaluable in critical situations. The problem here, of course, is that these salty paddlers are also more likely to charge the bigger drops and choose the more challenging lines on intermediate rapids. These added subjective hazards increase the likelihood that the expert boater will eventually require assistance from the less experienced members of the group (most of whom are ill-equipped to deal with complex emergency scenarios). Fortunately for the boater pinned on the midstream rock, the first kayaker through the rapid was a practiced Swiftwater Rescue Technician and was able to work quickly back upstream to take charge and initiate a successful rescue operation. Tales of terror such as these bring to mind the oft-repeated phrase: “You don’t learn safety skills for your own benefit. You learn them for the benefit of your partners.”

How do you measure up? How about your crew? When you head out to the swollen rivers and creeks this spring, make sure you know who’s got your back, and be ever ready to make the difference between a good campfire story and a tragedy. A few hours of practice each year can save you from a lifetime of regret.

This story originally appeared in our Spring 2007 issue. Since then, safety has not become any less important.