A Treasure State Treasure

A quick tour through Virginia City.

With only 150 year-round residents, Virginia City, the county seat of nearby Madison County, is the least-populated county seat in the State of Montana, barely edging out the 188 fine citizens of Winnett in presumably godforsaken Petroleum County. On any given day during the off-season—when the district court is in session—Virginia City probably has the highest number of lawyers per capita of any place in the nation.

Virginia City is of course a crown jewel of Montana and western history. Once Montana’s territorial capital during the height of its gold rush, it faded into obscurity when the gold ran out and the twentieth century got underway. It always remained the county seat of Madison County, however, and thus fell into a fortunate historical accident. Fully isolated, and with no growth to warrant any new buildings, nobody ever bothered to tear anything down. But with the county government still running, and the courthouse still filling up with lawyers when necessary, it never quite attained full ghost-townhood either, like so many of its sister boomtowns. Virginia City is, therefore, a fully-functioning Montana seat of government that happens to be frozen in the late 1800s.

As Montana’s most fully preserved authentic western town, Virginia City is a tourist magnet. Visitors can mingle with genial folks dressed in period costumes, take a gander at the largest collection of old-west memorabilia outside of the Smithsonian Institution (although numerous backyards around Bozeman also meet this criteria), and ride Montana’s only operating steam locomotive back and forth to Nevada City a couple miles away. The train is a concession to tourism; the railroad never actually went through Virginia City. But no matter how cheesy the local tourist culture gets, the buildings that remain are a little too authentic, and the history lesson a little too blood-soaked for Virginia City to ever descend into a full Disney-style whitewash.

Virginia City was Montana’s first incorporated town, and was home to both the first school and the first newspaper in Montana. At one point, upwards of 10,000 desperate people called this place home, many looking for gold and many more poised to take advantage of those who did. The gold shipped back east during the 1860s is credited by some with having had a decisive effect on the Union victory over the Confederacy during the Civil War. Virginia City lay in Union territory, but was populated largely by Confederate roughnecks, and this dynamic was responsible (along with the untold wealth scattered about) for much of the lawlessness and violence that pervaded the war years and after.

As good Montana schoolchildren know, the Montana Highway Patrol still bears the cryptic “3-7-77” on their shoulder patches in homage to Virginia City’s heralded “Vigilance Committee” which decisively dealt with the problem of murderous road agents. The Highway Patrol hopefully takes more inspiration from the Vigilantes’ role as Montana’s first police force, and less from the Vigilantes’ lynch mob tactics and series of summary executions. Of course no one is certain as to what 3-7-77 actually means. It could be anything from the dimensions of a grave, to an indication of a Masonic conspiracy. The evidence suggests, however, that 3-7-77 did not come into use anyway until a later wave of vigilantism in Helena during the 1880s, perhaps referring to the practice of sending the local riffraff to Butte via the three-dollar stagecoach that left at seven a.m.

In 1864 a federal judge appointed by President Abraham Lincoln convened Montana’s first grand jury in the dining room of a hotel in Virginia City and began enforcing a formal criminal code. The judge made note of the Vigilantes’ exploits in lynching more than two dozen suspected road agents, but declined to rebuke them. Frontier justice was better than no justice.

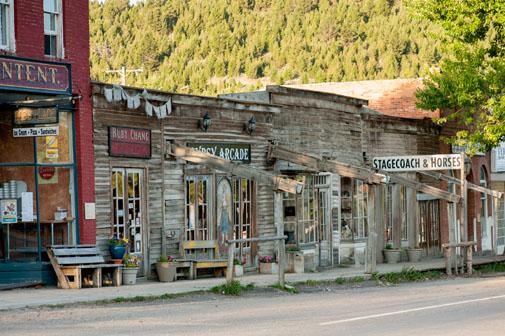

Apart from the modern sights and sounds designed to capture tourist dollars, Virginia City appears largely as it did during the boom years. Well, the buildings probably weren’t as run-down back then as they appear now, but you get the idea. Two theories of historical authenticity collide in Virginia City. Some argue that the best efforts should be made to restore old buildings to their original appearance. When done right, careful use is made of authentic materials and techniques, but nevertheless, over time, replacement parts can overshadow the originals.

The second theory, which holds that authentic buildings ought to just be left to fall over when they want to, usually wins out in Virginia City. If nothing else, you are looking at the real thing. Concessions are made of course. The state now owns about half of the historic buildings (while heavily regulating the rest) and wouldn’t likely allow any of them to fall over in this day and age. The charm of this second theory is that the visitor can peer at the actual buildings, for better or worse; not just as they were, but as they are, and as they continue their losing battle against time and the elements.

So much of Montana’s history is bound up in Virginia City that it would be worth visiting even if the historic buildings were all razed and replaced with strip malls, or something really obnoxious, like a women’s prison. Apart from their historical pedigree, the buildings themselves would be worth visiting simply as authentic examples of period architecture (even if everything could clearly use a new coat of paint). And the place itself, the gulch in a high mountain valley, where the streambeds and soil gave up so much gilded wealth, is a unique intersection of the earth and high human drama, worth visiting even if the town is often overrun with lawyers.