River of Raptors

Tracking the golden-eagle migration from high in the Montana mountains.

It’s windy at Duck Creek Pass in the Big Belt Mountains. It’s the kind of wind that shreds eardrums, forcing full-body tilt across steep, open slopes. The kind of wind that, in Montana, come September, lofts iconic birds of prey high along the spines of narrow mountain ranges.

If you’re a golden eagle migrating south to wintering grounds, then the wind at Duck Creek Pass is a good thing. If you’re Adam Richardson, face to the sky, dug into a blind rigged from downed trees and a camouflage tarp, counting raptors at 8,100 feet, then the wind is... also a good thing.

“I like watching apex predators in action,” says Richardson. His hair might be brownish-red or reddish-blond, graying maybe; hard to say, it being shorn close and snugged under a skull cap. The exposed skin is rubbed with sun. Reclined on both elbows, legs levered out before him, his voice quickens as he compares a golden eagle diving for a mallard to a wolf running down elk in Yellowstone.

“The eagle is folded, wings pulled in, he’s already in a stoop. All the mallard can do is try to gain elevation. I could just watch that until the end of time.”

Richardson’s been watching golden eagles from Duck Creek Pass since the last week of August, when North America’s largest hunting bird, Aquila chrysaetos, began soaring down the Rocky Mountains from northern breeding grounds. Counting them is tricky. The species prefers undisturbed mountain landscapes riding up against open grassland with prime hunting opportunities. Scattered in remote locations across a broad home range, populations are difficult to locate, even harder to access, and challenging to track. Until the birds move. When freeze-up puts the hurt on the hunt, northern breeders surge along predictable routes, from the Arctic south into central Mexico.

Like a compass cutting clear across a map, the Big Belts beckon.

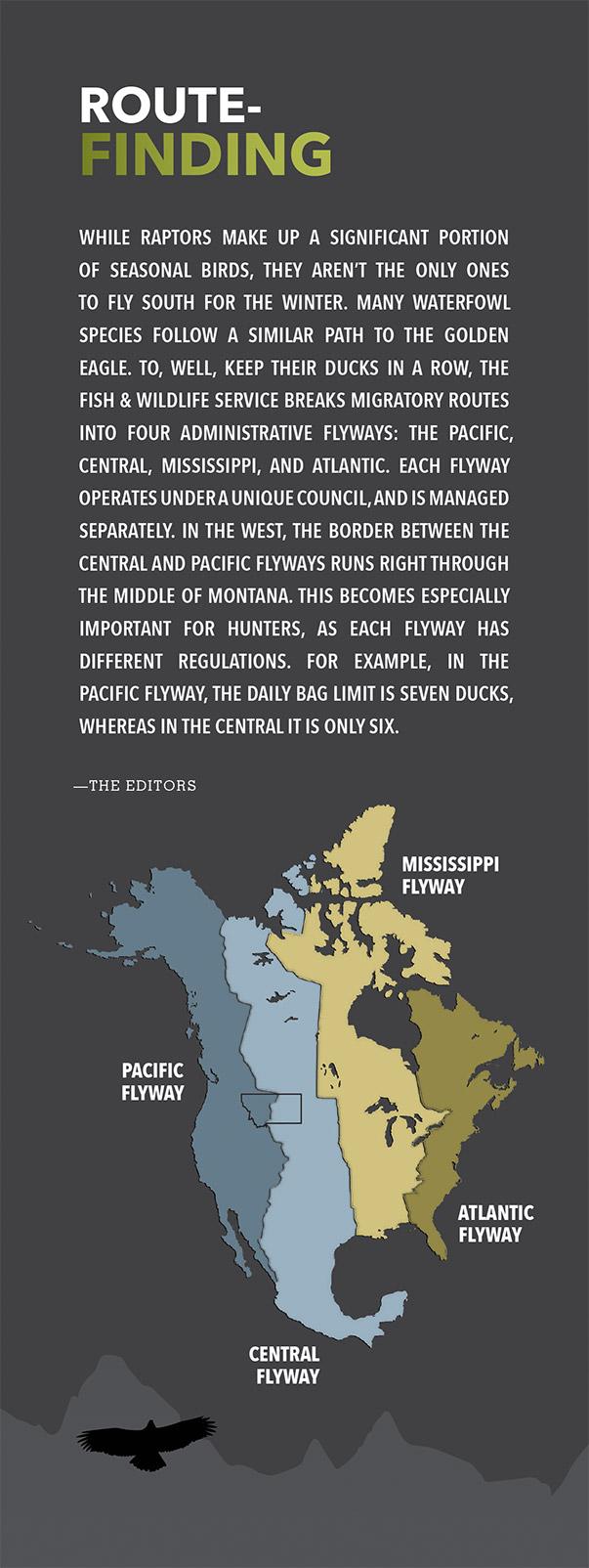

The front ranges form an obvious shore alongside Great Plains grasslands pulsing with prey. Prevailing westerly winds collide with ridgelines running north-south, forcing air to mount their stony flanks. Uplift funnels golden eagles and other raptors over high, narrow terrain by granting reliable, long-ranging expanses to gain momentum. Some corridors offer fortuitous overlap with roads. Where untamed currents of weather and wildlife converge on topography and access, counters amass tallies along the length of the flyway to secure ecology’s data arsenal: long-term population trends, of multiple species, at low cost.

Richardson makes the most of his $50 daily stipend. When he strides downslope, whether it be to measure wind speed, rig an owl decoy, or estimate cloud cover, he is hungry. He has an appetite for landscape and animal behavior; he eats data, especially when it comes to raptors, heralded as important biological indicators of ecosystem health. One doesn’t immediately register his resume of experience until parking beside him on the ridge for an afternoon: he has studied shorebirds in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, pedaled a bike through Alaska’s Brooks Range, and watched mosquitoes run caribou herds neck-deep into the Bering Sea. Between gusts that scour skin pores, he lifts binoculars to report, “sharp-shinned hawk—juvenile” while a deft wrist stroke marks some hidden spreadsheet in his lap. Before long, it’s clear that the lanky nomad birder has stealthily offered field pointers on red-tailed hawk plumage while doling out insights from prolonged adventuring cross-continent—by foot on famed long-distance trails, by bicycle from Reno to Prudhoe Bay, by canoe down the Yukon River from forest to sea. He’s guided river trips at Big Bend, tracked ruffed grouse in Wisconsin, counted waterfowl in Michigan’s Mackinac Straits, and surveyed for woodpeckers, northern goshawk, and red crossbills in Idaho.

He counts raptors. From 2017 through 2019 he was one of two primary observers at Bridger Bowl, the unique ski-hill observation site northeast of Bozeman that, since 1992, has claimed one of the country’s premier perches for observing storied numbers of golden eagles and other migrating raptors. With a record count of 3,532 raptors in 1998, fall totals at the Bridger site range between 2,000 and 3,500 migrants—over half of them, on average, golden eagle.

But at Duck Creek Pass in the Big Belts, discovered in 2007 as a significant flyway, counts have consistently boasted higher numbers of goldens than the Bridger site, just 60 miles south. In October 2014, 284 migrating golden eagles winged by in less than seven hours; in September 2015, 2,630 were observed, one of the highest passage rates for that species in North America; in 2017, over 70 percent of migrants were golden eagles.

Weather is the wild card. Wind patterns and storm fronts often determine flight paths, and those patterns are shifting with climate disruption. At Duck Creek, an access road choked by snow curtailed the 2018 count and nixed the 2019 season entirely. But the data potential under challenging conditions aroused Richardson’s hunger for epic raptor observation. In 2020, he reestablished the site as the primary—and solo—counter, under the banner of Montana Golden Eagle Research.

“There were 4,389 raptors counted at Duck Creek Pass in 2016,” he says. “If you’re going to count them in the U.S., that’s the place to do it.”

Converging Currents

“Raptors in Montana have it relatively easy,” says Richardson, comparing the concrete sprawl straddling Atlantic-region flyways to the agricultural sweeps along the Rocky Mountain Front that still support prey populations while protecting large tracts of land from the fate of subdivisions. “It’s a uniquely Montana thing, to have this pattern of land intact and in line with where the birds are going.”

From Alaska’s Brooks Range or the Yukon tablelands, most birds gravitate toward the reliable updrafts of the front ranges. They cross from Alberta into Montana and trend toward Yellowstone National Park to coast on through Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico, some making it as far as the Chihuahuan Desert.

In October 2014, 284 migrating eagles winged by in less than seven hours; in September 2015, 2,630 were observed... in 2017, over 70 percent of migrants were golden eagles.

Researchers want to be where the birds are. In Montana, flight lines through Glacier National Park encompass the Continental Divide and converge around Mount Brown. Many birds coast down the Swan Range, visible from Jewel Basin. The main migrant surge makes for the divide north of Helena; from Roger’s Pass, with grasslands over their eastern shoulders and wilderness tracts at their backs, ravenous raptors only partway through their journey behold the threshold of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Like a compass cutting clear across the map, the Big Belts beckon.

This narrow island range, its single ridgeline aligned north-south with eagle transit on thermal lift, is isolated by ranchland and rivers—on the west by the Missouri, on the east by the Smith. These are corridors rife with golden-eagle meals: jackrabbit, ground squirrel, migrating waterfowl. The ridgeline consolidation is intensified by Canyon Ferry Reservoir; the water’s slow, even heat-release kills thermals. Shunting around the water obstacle, birds converge on Duck Creek Pass; from there, many stream along the Bridgers toward Yellowstone.

“South of the Bridgers, the singular ridges fizzle out and become many-branched,” says Richardson. The flyway becomes broader as birds contemplate updraft potential across the Beartooth, Absaroka, and Gallatin Ranges.

Bridger Anomaly, Big Belt Bounty

Fortune can hinge on a single driver. When counting raptors at elevation, that driver is weather.

At Bridger Bowl, home to both east-facing cold smoke and consistently stellar raptor numbers, the same conditions that set the stage for a celebrated ski hill can impede access to migrating eagles, obscure visibility, and stymie a count site’s potential. In 2019, successive storm fronts raced their winter mark to arrive early. Freezing fog socked the mountain and lingered through October as snow level dropped quickly down the ridge.

“The weather parks in a gap just north of the helipad,” says Richardson, who, as counter, rejected a daily grind from Bozeman and opted to camp instead in the patrol hut just south of the concrete landing platform. “It settles in, then you’re up there trying to count and the west winds drill you in the face with rime.”

It takes more than a winter blast to blow Richardson off his game. Pursuing eagle numbers into mid-October, he ascended the trail on skis through treacherous terrain with windchill dipping to -30º Fahrenheit.

But effort won’t trump adversity if the birds aren’t there. According to Richardson, “Past the second week of October, the birds don’t have an affinity for the Bridgers. Weather patterns are changing. They’re moving down to the valleys with powered flight. Part of the population isn’t even going to the Bridgers. They might be veering over Battle Ridge, down the east side of the Crazies.”

Richardson, charmed equally by avians as he is by adversity, gave up his own ground to match their chosen path.

“I saw the numbers they were getting at Duck Creek Pass. At the end of the day, if you’re sitting out there in the weather, I know it’s not scientific, but... I want to see as many as I can.”

One advantage concentrating raptor numbers at Duck Creek Pass is sight line. “At Bridger,” says Richardson, “you’re on the helipad. Sacagawea and Naya Nuki are six miles north, so you’re looking through the spotting scope at big birds. You’re blind to Bridger Canyon where birds are flying in certain weather, and to the west over the Gallatin Valley when the clouds sock in.”

Depending on wind, species, and fire haze, all flyways at Duck Creek Pass may be visible: the distant cruise hugging the lakeshore; the hopscotch through hayfields to kettle up on thermals; the up-canyon sweep to the pass and on along the ridge proper. Richardson can typically see all routes, sometimes without binoculars.

“I’ve had days when I could reach out and touch them. You can see how many birds have full crops (throat pouches to carry food before digestion).”

Close observation is aided by owl decoys Bubo and Bobby. With Richardson as lone observer, the owls, each secured with a dusky-grouse wing, draw far-flying migrants closer to the blind. Bubo taunts raptors from the top of a PVC pipe 100 yards downslope; the upslope owl has a bobble head—Bobby. Both receive regular thrashings by raptors and ravens, bouts that read like comedy skits in Richardson’s blog, which he updates nightly in his tepee alongside flight summaries and weather reports.

The decoys stack data collection with diversion for the solitary, resolute observer. “You get to see how each bird flies,” says Richardson. Without the owls, many accipiters would flip by below him, migration undocumented, antics unrelished.

Antics notwithstanding, there is timetable and procedure, a rhythm to the day, to the season. Broad-tailed hawks, northern harriers, falcons, and accipiters fly first; then eagles, juveniles earlier with adults clustered toward noon, with another peak in the evening. There are measurement protocols on the half-hour; numbers to input, trends to interpret.

But not all insight follows science. Any student of the backcountry knows that.

There were 4,389 raptors counted at Duck Creek Pass in 2016. If you're going to count them in the U.S., that's the place to do it.

Sanctuary Shared

To study a raptor, in Richardson’s view, is to understand the animal on its own terms. Immerse yourself in its landscape and you learn what is normal, what is novel. Put in the time, you receive unexpected gifts. Some alight, like the single rufous hummingbird levitating over the orange parachute cord inside his tepee. Other insights flock in at the whims of weather.

“They ride fronts,” Richardson says of the way golden eagles respond to recurrent squalls. “They typically arrive a day prior to a major weather event. Each wave of winter weather seems to kick up another wave of migrants coming through. I’m not saying they’re a flocking bird, but they definitely come through in pulses.”

Every night, if he finds enough bars on his phone, he checks weather reports from his tepee. He checks the Mount Lorette site in Alberta—how many goldens passed that waypoint? How many days ago? Factoring in storm fronts, he predicts the next day’s intersection of wind and wing on the ridgeline that defines his primitive home front.

It’s a home he commits to hold down every fall for the next 10 years at least. In 2020, when snow blasted the pass and swamped the observation point with drifts, Richardson zipped deeper into his camo parka, grunted back up the ridge each morning, and repeatedly shoveled out the blind, only to have it fill again. When deepening drifts thawed and refroze into ice walls, Richardson persevered with counting—he trusted his endurance; he did not trust his Subaru. He rammed slapdash armloads of gear into his car in the middle of a harrowing storm—tepee, woodstove, and all—and hurtled down the east side of the pass to make rough camp by dark, 900 feet lower at Gipsy Lake.

Then he skied up the ridge four miles. To count birds.That evening, through darkness, he watched over 200 snow geese fly in to shelter in the nearby stubble. By morning, the center pole of his tepee was bowed. “You couldn’t see the wheel wells of the car. It was cold smoke, light and fluffy, three and a half feet deep. Lesson learned. I needed to see on the ground what happens when you get that much snow overnight.”

“It was clear the drifts weren’t going anywhere. It was difficult to ski, the drifts were 12 feet tall in places, windblown cornices, I had my helmet on. But the days I got up, there were 80 birds in two hours. If there’s wind, the birds will be there.”

With weather, he explains, there’s a positive and a negative. When the mercury drops in the Big Belts, “You have to look out for frostbite... having enough wood... getting snowed in... if the battery on your car still has a charge... But you have snow to melt. I look forward to getting the woodstove fired up. That’s my carrot on the stick.”

Richardson sets his sights on the long-term forecast.

“The birds are on their schedule, I’m on mine. I’m on the top of a mountain in a cold place, wearing a parka, dealing with early-season winter storms. Weather is what it is. At the end of the day, the raptors are dealing with that, too. It makes me more aware of how climatic conditions affect them.”

A migrant himself through cyclical vagaries of weather, he brings visceral knowledge that these apex predators of landmark western topographies are a reflection of their journey, their habits, behavior, and morphology all shaped by the landscape. Perched on his mound of experience and insight, he surveys a familiar horizon.

“I know the landscape these birds are flying through. As long as they’re migrating past me, I know their habitat is somewhat intact.

But that landscape is changing. As climate warms on a global scale, it alters migration patterns. Raptor numbers suggest that migrants are moving south ahead of schedule; counters have backed start dates by weeks into August to account for earlier passage. And the streams of raptors once counted at Bridger as “a steady trickle, maybe 60 to 80 birds a day,” is transitioning to tidewater as early winter-like weather concentrates the birds through intermittent surges of flight days. In the Big Belts, Richardson can see the possibility of golden-eagle numbers eclipsing Bridger counts and laying the foundation for a new template of understanding migration.

“The birds are moving through in large numbers between early-season winter-storm events,” says Richardson. “It would appear climate disruption is having an impact on the physical nature of migration itself.”

As for big numbers in the Big Belts, Richardson remains hungry. Among other things this season: another full-time counter, a smarter base camp, lower on the west side of the pass where wind-drifted snow won’t plague sight lines and access. Less fire haze—for that, he’ll probably still go wanting.

“The Big Belts are a great fit for me. They’re more remote. It’s more effort. You have to want it. The reason I like doing this research is that at my age it brings all of my skills that I’ve learned in life together. I’m very organized. Logistics come easy to me. Living outside and being happy and thriving in tough conditions is easy for me.”

He has found his place to roost.

“I came to field work late in life,” he says. “The thing I like about science is there is no dogma behind it. I am fortunate to see how the world is put together.”

At Duck Creek Pass, Richardson grasps insight that he’ll tuck away with numbers. He wields tools like talons: binoculars, anemometer, the struts of science in a web of adaptability, his particular pathway over land and life, his wits, his guts. At his back, a terrain of data, a mass of predators pushing down from northern ranges. In front of him, the full country of where they might be headed.

It’s quite a view.