All for One

Access to the Lionhead area is the result of a rock-solid partnership between cyclists, horsemen, and the Forest Service, a rare case of collaboration where the results speak for themselves. With the Custer-Gallatin undergoing its Forest Plan Revision, that could soon change.

Two hours south of Bozeman, along the Idaho-Montana border, nearly 50 miles of pristine singletrack spread out across the high alpine of the Henry’s Lake Mountains. From Targhee Summit, at an elevation of over 10,000 feet, the Gallatins, Taylor-Hilgards, Spanish Peaks, and Tetons thrust upward toward an azure sky. Summer sunlight reflects off Hebgen Lake as wind rips across its surface, whitecaps visible even at this distance. The timber groans under the weight of the gusts, a reminder that fall is on its way.

This is the Lionhead. Ryan and I rest atop a saddle after riding up from the Targhee Creek trailhead. We parked just off Hwy. 20 between West Yellowstone and Island Park, and now, from our elevated vantage point, we can see for miles in all directions—a welcome reward after a grueling climb. On this particular weekend, we’ve yet to pass another person, and there was no one at the trailhead. The only other sign of life is a set of bear tracks in the dirt.

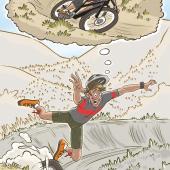

As we take a moment’s pause, a mountain-goat family reveals itself on a distant knob, indifferent to and unaware of our struggles to ride in their alpine back yard. For them, the effort is no more than a walk in the park; for us, it’s exertion at our limits.

We’re here to sneak in one last high-alpine ride before the weather changes, which it can do quickly in the mountains of Montana. We’ve chosen the Lionhead for its remoteness and lack of crowds, but also for its sublime singletrack. For many, the Lionhead represents everything that large-scale, remote, backcountry settings can offer: solitude, wilderness, challenge, reward. This is made sweeter by the fact that users invest personally in the stewardship of this place, making its maintenance their privilege and its preservation their duty.

“The Lionhead matters because of the scenery and the riding,” says the Southwest Montana Mountain Bike Association’s (SWMMBA) advocacy director Adam Oliver, “but it matters most because we take care of it. Here’s this place we love… that’s the important thing.” When reflecting on his connection to the Lionhead and the trails here, Oliver recalls driving past the Henry’s Lake Mountains several years ago. “I thought, ‘I wonder if I could get up there.’ The Lionhead is just one of those spots.”

Snacking on jerky and chocolates, leaning into a stiff wind, it’s easy to see what he means, although it’s difficult to put the sentiment into words. “Unique” is too simple a term to capture a place, especially a place like this. Looking north toward the core of the snow-dusted Madison Range, we see in its shadow a high-elevation plateau, uninterrupted for miles. No trail crosses here; few people have plied the interior of this massive expanse. To the west is Targhee Peak, towering over the saddle on which we sit. To the east is Hebgen Lake, and in the distance, West Yellowstone; beyond that, Yellowstone National Park. To the south, there’s nothing but timber until the massive uplift of the Teton Range. A quick-moving squall has left the high peaks covered in snow.

The climb to this point is grueling, but hardly unattainable. The first few miles of the Targhee Creek trail meander along its namesake waterway at a leisurely incline, dipping in and out of the timber from time to time to traverse sage-covered meadows. The tread is flawless and the only time we’re off our bikes is when we pause to photograph the cliff-clinging antics of amountain-goat clan. To gain the drainage’s basin, we churn up challenging-but-cleanable switchbacks, cresting a ridge before linking up with the Continental Divide Trail (CDT).

Ride west, and we’d link up with the Mile Creek trail, part of the CDT and a masterpiece from the late, great trail-builder Terry Johnson. Ride east, and we’d have several options, like the Sheep Creek epic, Watkins Creek, or Targhee Pass. We’re camped near Targhee Pass so we take that option, knowing we’ll be back to ride the others.

The trail quality in the Lionhead rivals any anywhere in the state, and the scenery takes the cake. That’s why volunteers like Corey Biggers and Adam Oliver spend their summers here, organizing others to join in on the effort. They remove hundreds of trees from miles and miles of the CDT, connecting almost the entire expanse from Yellowstone National Park to Monida near Interstate 15.

“Without those folks, a lot of trails wouldn’t open,” says Forest Service Region 4 trails staffer Jarrod Hansen. According to Hansen, the Forest Service relies on the volunteers. “Our [trail] projects are informed by Corey. He’s the main guy opening trails. [Corey and the other volunteers] understand the needs. They’re great partners.” While other groups such as the Montana Conservation Corps contribute, Hansen reiterates the commitment of Biggers and his fellow volunteers: “It’s amazing what they do for us.”

The benefits to the Lionhead and CDT trail access have been so pronounced that the Forest Service recently presented Biggers with an award for his service. This show of gratitude was even more meaningful because it was presented to Biggers and Clark Kinney, a Gallatin Valley Backcountry Horseman. Backcountry horsemen and mountain bikers aren’t always the closest of friends, but in a place as singular as the Lionhead, shared passion has lead to collaboration instead of friction, and created friends instead of foes. In a letter addressing a separate trail-clearing effort, the Horsemen thank Biggers and the Montana Mountain Bike Alliance for their “willingness to team up,” going on to say, “our combined efforts … are an example of what teamwork can do.”

This collaborative effort is no more apparent than at the annual Lionhead trail-clearing weekend. What started as a partnership between a few mountain bikers and a few horsemen has grown into a weekend-long gathering involving dozens of committed volunteers. Participants arrive Friday evening, camp, and then rise early to head into the mountains. The horsemen leave first, packing rakes and chainsaws on their trusty steeds. Bikers come up behind the horsemen, break into teams, and clear dozens if not hundreds of fallen trees from the trail.

For over ten years, this event has taken place in early July, snowpack permitting. Because of this Herculean effort, the entire zone is largely free of deadfall in time for the summer thru-hiking season, a gift most CDT backpackers never know they’ve been given. Without this partnership, the Forest Service would struggle to clear the area every other year, let alone every summer, according to Hansen.

While the Lionhead is most closely associated with the Bozeman community, its influence extends well beyond Gallatin County. “The Lionhead is the premium destination for challenging alpine riding in the country,” says Lynne Wolfe, board secretary for Mountain Bike the Tetons. “It’s my absolute favorite place—period,” Lynne continues. “It makes me feel small, and honored to be there. Every year, my husband and I reciprocate by giving back. Every year we do trail work and connect with other mountain-bike lovers [at the trail-clearing weekend].”

Jay Petervary, a ten-time Ultra Iditirod champion, six-time Tour Divide record holder, and Victor, Idaho native, agrees. “It’s amazing to ride in such an ecosystem, just outside the Park,” he says. “It’s true backcountry, high-alpine riding.” For someone who spends his life covering vast distances on a bike, in locales all over the world, that’s saying something. But Petervary does more than just talk. Last summer he donated a portion of proceeds from his Gravel Pursuit race in nearby Island Park to trail-clearing efforts in the Lionhead. With commitment like that, stewardship efforts can continue for years to come.

Given the Lionhead’s propensity for partnership-development and its impassioned devotees, you might assume that all is well in the mountains above Hebgen Lake—and who could fault you? The truth is, a majority of the Lionhead’s trails sit inside a Recommended Wilderness Area (RWA) within the Custer-Gallatin National Forest. While several access points lie within the Caribou-Targhee Forest, the rest originate in the Custer-Gallatin, a unit currently undergoing a Forest Plan Revision. The management recommendations within that revision could limit or close bike access to the Lionhead, an outcome volunteers dread, especially given their personal commitments to the area.

For Wolfe, there’s hope. She puts her faith in the partnerships, saying, “We can work for a better solution. This is an important place we need to respect, and I strongly believe mountain bikers should be there.” Petervary implores bikers to “know the work that it takes—many individuals with a strong passion. You don’t take no for an answer.”

Oliver, too, is optimistic. “We’ve seen a recent surge in effort and awareness by the bike community. Mountain bikers have been volunteering more, supporting trail projects, donating, and building relationships.” He goes on: “Although Montana has probably seen bicycle access restricted more than anywhere, the issue has gotten a lot more attention as a result. The preliminary maps released by the Custer-Gallatin National Forest have two management alternatives that preserve all or nearly all trails on the Montana side of the Lionhead for biking. This is no accident. Saving the Lionhead is surely within reach if mountain bikers focus on commenting and continuing to grow our positive influence.” According to Oliver, forest planning has brought a variety of stakeholders to the table, and real progress has been made on the collaboration front. One potential solution would be re-designating the Lionhead a Backcountry Area, an official designation that provides a high level of protection without denying bike access.

As afternoon becomes late afternoon, Ryan and I snap a few more photos, finish our candy bars, and layer up for the ride out. Ryan goes first and I take one last look around, hoping this isn’t the last time I’ll ride my bike in the high alpine of the Lionhead. I think of Petervary’s insistence on action, Wolfe’s hope, and Oliver’s resolve. I think about the collaboration with the Backcountry Horsemen, Biggers’s selfless volunteerism, and the Forest Service’s appreciation.

At this moment, with our country’s social and political discourse being what it is, collaboration is something we should celebrate. Compromise is an ideal worth fighting for when the outcome makes sense. In this case, horsemen and hunters have partnered with mountain bikers—Donald might as well be sharing a shotski with Nancy and Chuck—to ensure that a cherished place is open to users across the recreation spectrum. Impacts are mitigated by a shared responsibility, and trust has replaced skepticism. A neglected resource has secured devoted stewards, and an agency has empowered citizens to care and be accountable.

For now, all visitors to the Lionhead can do is wait. The Custer-Gallatin’s Forest Plan Revision is ongoing, with final recommendations coming next year. This will be an anxious summer, with many wondering if it will be the last they spend biking in the Lionhead, and many more wondering what will happen to the resource without the committed volunteers.

All of the Above

by the editors

Developing a management recommendation for landscapes stretching from West Yellowstone to the Black Hills of South Dakota is no easy task. Appeasing the wishes of dozens of user groups, numerous industries, several local governments, and countless citizens is even harder. The Custer-Gallatin National Forest has been hard at work for almost three years already, gathering information and synthesizing that information into several management alternatives. Their final recommendation will not rigidly adhere to a specific alternative, but will rather take bits and pieces from several. To learn more about the alternatives, including trail closures, visit fs.usda.gov/main/custergallatin.

Heroes on Horseback

by the editors

Every spring and summer, horseback riders assist in the clearing of hundreds of miles of trails across southwest Montana. Without their efforts, many of our favorite trails, like South Cottonwood, would either remain blocked by downed trees or at least be deadfall-laden later in the summer. If you’re interested in assisting with their efforts, or just going on local trail rides with a group of fun-loving equestrians, check out the Backcountry Horsemen of Montana at bchmt.org.