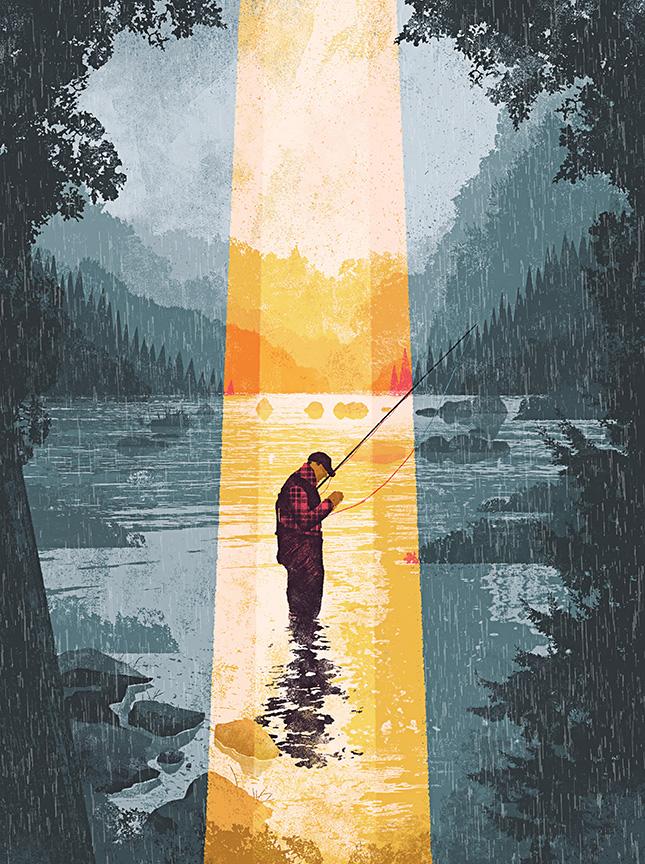

Lost & Found

It's easier to see clearly when you know where to look.

I lost my lanyard while fishing yesterday. Or so I thought. It started out as a relatively warm early-spring day nymphing on the Yellowstone River, sun occasionally peeking through the clouds, with only moderate wind, nothing like the gales that can blow through Paradise Valley in the winter. In about two hours of fishing, I caught three 14- or 15-inch rainbows (one even jumped) and one whitefish. Not bad for this time of year. But then the wind came up and the temperature began to drop. My fingers throbbing with the cold, I decided to call it a day and walked downstream to the truck.

When I went to remove the split-shot from my leader, my forceps weren’t dangling on my chest like they normally are. Without much hope, I retraced my steps upstream, scanning the ground as I went. No luck. I sat down for a moment on a flat-topped boulder to mourn the loss of my lanyard, my nippers, my collection of tippet spools. When I stood up, I heard a faint jingle from behind. Reaching up to my neck, I made a happy discovery. My lanyard was there, where it always had been. It had somehow gotten pulled around my neck and was hanging down my back, out of sight. Uplifted by my find, I headed back downstream to the truck, where I sat for a while with the motor running, warming my fingers in the heater’s blast.

I have battled depression and nosebleeds throughout my adult life. In some ways, my afflictions are similar. Both tend to arrive without warning, without any apparent cause. Both linger an uncertain length of time, resisting attempts to staunch the bleeding. When an episode subsides, anxiety remains about when the next will begin. Both tend to occur in clusters, with long periods of quiet between. And both can leave behind indelible stains, on favorite clothing or the soul.

I won’t attempt to describe here the subjective experience of depression; others more literary than I have done so with sensitivity and grace. Read, for example, William Styron’s “memoir of madness,” Darkness Visible, and you will come away with an appreciation of the power of the malady.

I did not grow up fly fishing. My early fishing exploits were with bait, spinners, and spoons. Some of my fondest memories of my youth are of drifting hand-caught grasshoppers toward the small trout that inhabited the tiny creek that ran by our Colorado mountain home. The occasional 12-incher was a trophy. The 18-inch rainbow that I caught on a spinner in one of the creek’s few deep pools was an almost-unimaginable monster. The friend that I fished with that day claimed he knew the property’s owner, and that we were allowed to fish there, but to this day the memory is tinged with the embarrassment of trespassing.

My four years at a small college in the Midwest are when my depression first came calling in earnest. And I had a veritable gusher of a nosebleed while making my decisional visit to that same college. Despite my shame over the ruined pillow that I left behind, I decided to attend the school. Perhaps I should have taken it as an omen of the psychic stains that were to come.

When I returned to Colorado after college, my affair with fly fishing took root. The peace I found while exploring the small lakes and streams near my home was unlike anything I’d experienced during my bait- and gear-fishing days. I haven’t looked back. Besides a couple of deep-sea fishing trips, I haven’t thrown bait or lures since. I’ve always contended that any style of fishing is fun when you’re catching fish, but only fly fishing is still fun when you’re not. To say that fly fishing helped get me through the stress of graduate school would not be an exaggeration. In my memory, these were the happy years, the calm before the storm.

Eight years in North Carolina were a disaster. I was unsuited to be a professor in a high-powered business school. The climate oppressed me. And the fishing. We made our home in the Triangle, too far from the ocean and too far from the mountains. The nearest tailwater was a two-hour drive. Still, I spent many a day knee-deep in the warm water of local rivers, chasing panfish and the revelatory small bass. Between the therapy sessions, the hospitalization, the ever-more-desperate pharmaceutical interventions. Fishing the streams and rivers of Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho pulled me through an otherwise horrible year as a visiting professor in Pullman.

I have cried on the water. Not often, but enough. At the end of a birthday outing to the Madison, when the joy of the special day gave way to the frustration of rising water and closed-mouth fish. When I sighted a No Trespassing sign at one of my favorite North Carolina fishing spots, a pool below a dam where I could catch crappies on nymphs in the spring, the owner a victim of overblown post-9/11 terrorism fears. But most times, I finish a day of fly fishing with a sense of satisfaction and a smile on my face.

Fly fishing has not cured my depression, any more than it has cured my nosebleeds. But I have often sought, and found, solace in its rhythms and rituals. Its quiet and calm. The beauty of its surroundings and its wild quarry. The hope that accompanies every cast. The friendships it has engendered. The painful memories, like the blood stain on my winter fishing pants, are but reminders of what I have overcome. And there have been the big changes, brought about at least in part due to my obsession with fly fishing. The move to Montana. Leaving academia and diving headlong into the business of fly fishing. Rivers full of fish truly are my happy place.

Perhaps my personal history has led me to be too quick to judge some of the trivialities of my beloved activity. The cynicism that seems to run rampant in the industry. The griping about how things used to be better. The hunt for trophy fish, and denigration of anything that doesn’t live up to that status. Dries versus nymphs. Flat-brimmed hats versus curved-bill hats. All this doesn’t really matter. At a deep level, fly fishing should be fun, is fun. And depression abhors fun. Nosebleeds are indifferent.

I have been fortunate to find most of the things that I’ve lost while fishing. The one notable exception would be my wedding ring. No deep metaphor here; the marriage has survived, despite everything. But the gold band remains on the bottom of the Gallatin River, or perhaps washed down to the mighty Missouri by spring runoff. But there was the fully loaded fly box dropped on the shore of the Bitterroot, retrieved after a careful retracing of my path. And the rod tip snatched by brambles in the gathering dusk on southern Virginia’s Smith River, miraculously reappearing in the dim light of my flashlight beam. And my lanyard, never truly lost.