Gone With the Word

In March, the Montana state legislature celebrated the completion of its 10-year effort to change the names of 76 places containing the word squaw. Though House Bill 412, the measure that first sought the name changes, was originally submitted over a decade ago, in 1999 Democratic Senator Carol Juneau of Browning made another push for the legislation with the support of Democratic Senator Diane Sands of Missoula, who in 1997 led an unsuccessful attempt getting the word, often regarded as derogatory, off the names of many well-known places in the state.

“It was time that Montana took a step to take the derogatory word squaw off place names,” she says about her decision to reintroduce the bill. “We recognized—and I recognized—the word as a derogatory word towards women, towards Indian woman in particular, and it really has no place in this state.” Senator Juneau represents a district that is 90% Native American.

What's In a Name?

“One reason why it’s considered offensive is because it’s said to be an Algonquian word for female genitalia,” says Dr. Walter Fleming, department chair of Native American Studies at Montana State. “It’s evolved to native people, particularly native women, as a slur, regardless of its etymology. So it took on a negative charge; it doesn’t matter what it meant in the past, it took on this derogatory meaning.” Dr. Fleming applauds the effort “to get off of the public record something that is offensive. In some ways, it’s reclaiming the landscape that is important.”

When asked about those who support keeping Montana’s “Squaw” places for tradition’s sake, Dr. Fleming noted that the names weren't the originals anyway. “It must have been called something before that,” he says, speaking of the time before settlers came west. “Lewis and Clark changed everything.”

The Milk River, though not carrying squaw in the name, is one widely known example. Fleming says the Hidatsa originally named the river “The River that Scolds the Other” apparently in deference to its distinctive branches. The Corps of Discovery allegedly changed the name in 1805, noting in their journals that the river looked like a cup of tea with milk in it.

Word Work

During the 10-year effort, Juneau and members of the “House Bill 412 committee"—including representatives of the state forest service, the governor’s Indian Affairs Coordinator, state legislators, and what Juneau calls “community people who just said ‘yes I want to help’”—volunteered their time to the effort.

“It wasn’t just a matter of our committee—the House Bill-412 committee—identifying new names for these sites, we had to work with all of the local communities,” says Juneau, explaining about why it took 10 years to complete. “We had to work with tribal councils, we had to work with county commissioners; we encouraged local groups and school groups to come up with names that had some significance to that area. Some of the tribes responded and identified traditional American Indian names that might fit or be part of their history.”

In January 2000 the United States Board on Geographic Names approved the first name change of this movement. (Name changes are not official until the USBGN accepts the proposal during its quarterly meeting in Washington, D.C.) An after-school group of kids from Helena called “Wakina Sky” succeeded in changing Squaw Gulch to Wakina Sky Gulch.

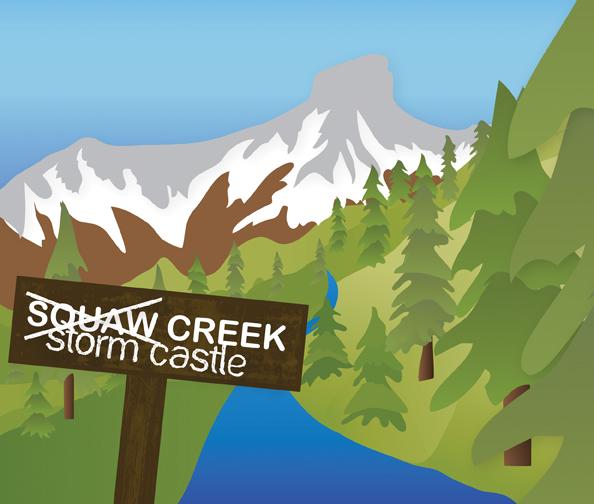

In 2004, Squaw Creek—located just outside of Bozeman on Route 191—officially became Storm Castle Creek, a name submitted by the forest service and which refers to the large rock “castle” atop an adjacent peak. “In March at the capital, we had finished with the place names for all 76 of the sites that were identified in Montana,” says Juneau proudly. “We thought it was important to… have a little celebration of that effort and recognize people who were significant in that effort.” Juneau estimates that only 10 to 20 percent of the names have yet to become official and are waiting for USBGN approval.

Learning Curve

A provision in the bill is the reason many people are unaware that place names in Montana have been changed and why many Bozemanites still don’t know that Squaw Creek has actually been Storm Castle Creek for the past five years. Part of Section 1 of House Bill 412 reads:

Whenever the agency updates a map or replaces a sign, interpretive marker, or any other marker because of wear or vandalism, the word "squaw" is removed and replaced with the name chosen by the advisory group.

This condition saves the state money by not having to replace signs that wouldn’t otherwise be replaced, says Juneau, and it also delays the time for the new names to be accepted and commonplace in Montana. “If we did some legislation that costs the state a whole bunch of money to redo things, it probably wouldn’t have gotten through,” Juneau explains.

“You’ve got signposts, maps, and other things that carry that name, so it will take some time” says Dr. Fleming. “But if you take away a name, you need to give it a new one. So it’s given people a way to turn a negative into a positive and more honorable option.”

Juneau is also patiently waiting for the disappearance of squaw. “It takes time. It took time to get all of those derogatory names on those sites, and we recognize that it will take time to get them off. It’s wonderful recognition of not only tribal history but also local history in some areas.”