Bears, Birds, and Bark

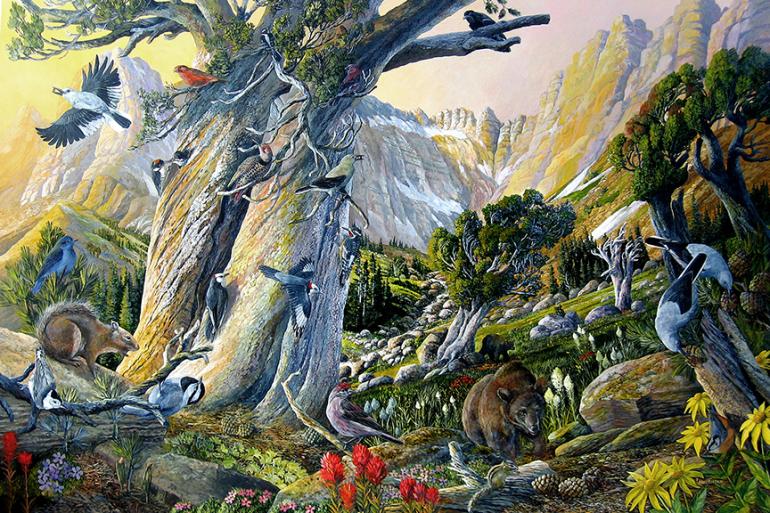

The tangled web of the whitebark pine.

After countless water breaks and switchbacks, you finally approach timberline. Before entering a world of ankle-eating scree, you’re greeted with one last chance for shade. Gnarled by the elements, whitebark pine trees sit in clusters. For backpackers, skiers, and climbers in the greater Yellowstone area, the whitebark’s crooked limbs signify altitude and solitude. More importantly, they means survival for animals like grizzly bears and pine squirrels. But because of fire exclusion, the mountain pine beetle, and white pine blister rust threatening its remaining stands, the whitebark pine is an ecological poster-child in peril.

Easily identifiable by its five-needled clusters, whitebark sets itself apart from its woodsy neighbors both in appearance and function. At timberline, it can be found as a single-stemmed sentinel or multi-stemmed cluster, thanks to the work of the Clark’s nutcracker which serves as its primary seed disperser.

Unlike lodgepole pines that depend on fire to open their cones, or Engelmann spruce and subalpine fir whose seeds are dispersed by the wind, whitebark pinecones rely on the nutcracker’s long, pointed bill to break off the cone scales and expose their seeds. The nutcrackers then cache the seeds anywhere from a few meters to several kilometers away from the seed source. Researchers have estimated that a single nutcracker can cache as many as 98,000 whitebark seeds in just one season.

In years with good cone crops, grizzly bears rely on the seeds as a major food source. Consisting of over 50% fat and weighing an average of 175 mg per seed (lodgepole seeds weigh 4 mg), the whitebark pine has the largest seeds of all conifers at subalpine elevations in its range. In good cone-crop years, grizzlies will feed almost exclusively on the seeds by raiding the caches of barking pine squirrels. Good cone years also keep the bears at higher elevations, off roads, and out of garbage cans.

Because it enables species like grizzlies and nutcrackers to survive in a community, whitebark pine is considered a keystone species of the upper subalpine ecosystems. And as a keystone species, its decline threatens the balance of the entire Yellowstone ecosystem.

Past fire management policies have suppressed natural fire regimes—and without fire, whitebark pines grow older and their stands become denser. Dense stands and mature bark provide a cozy home for the larvae of the mountain pine beetle that feeds off the tree’s inner nutrients. In the Gallatin National Forest (GNF), mountain pine beetles are slowly moving in from Yellowstone and establishing populations, says Roger Gowan, an ecologist with GNF.

White pine blister rust constitutes another, nonnative threat. In 1910, this arboreal infection was inadvertently introduced near Vancouver, BC and quickly spread. The disease produces cankers on branches and stems, ends cone production, and eventually kills the tree. While research has shown that only one in 10,0000 trees are genetically resistant to rust, all hope is not lost.

Efforts are being made by scientists and land managers to save the whitebark pine. In some areas of the GNF, stands of whitebark are being thinned through prescribed burning and selective cutting. Other measures include insecticides on mountain pine beetle populations. Organizations like the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation have been created to encourage research and restoration projects.

Because 47 percent of the greater Yellowstone area is potential whitebark pine habitat, backcountry users around Bozeman are likely to visit the high-altitude stands. And when their knees eventually give out and their grandkids wander past them up to timberline, hopefully the whitebark pine will still be there to give them a little shade, too.