Tooth & Nail

Doug Peacock’s conservation crusade.

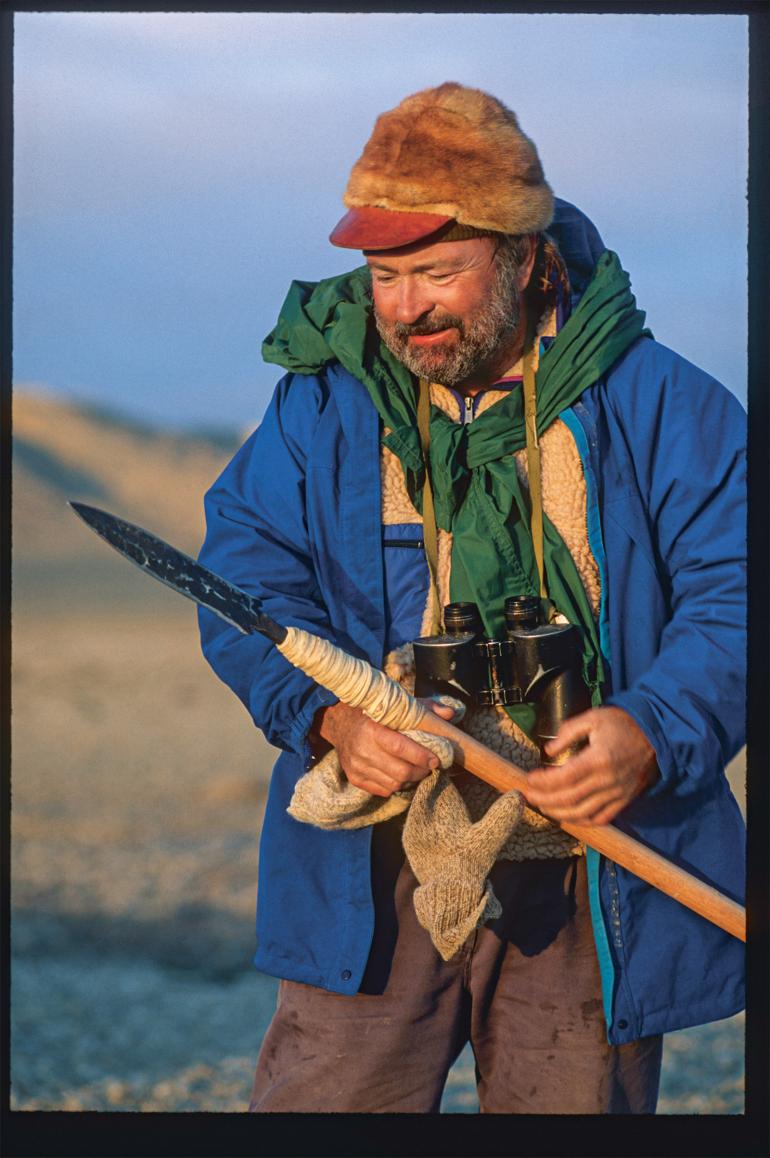

Doug Peacock isn’t afraid of a good fight. That’s clear down to his doormat, which reads, “Come back with a warrant.” To the left hangs a wood-and-iron spear, which Peacock brought with him to the Arctic to fend off polar bears. The spear waits for its next call to duty, idle for now.

Peacock opens the door and warmly invites me in. His home is neat but clearly lived in, and it smells like the surrounding landscape: sagebrush, wild grasses, and mountain air. His collies, Hector and River, greet me eagerly while his orange cat, Oliver, eyes me from afar. Peacock offers me a beer before realizing that he only has one left in the fridge. He declares this deficiency “unforgivable” and hands the lone beer to me.

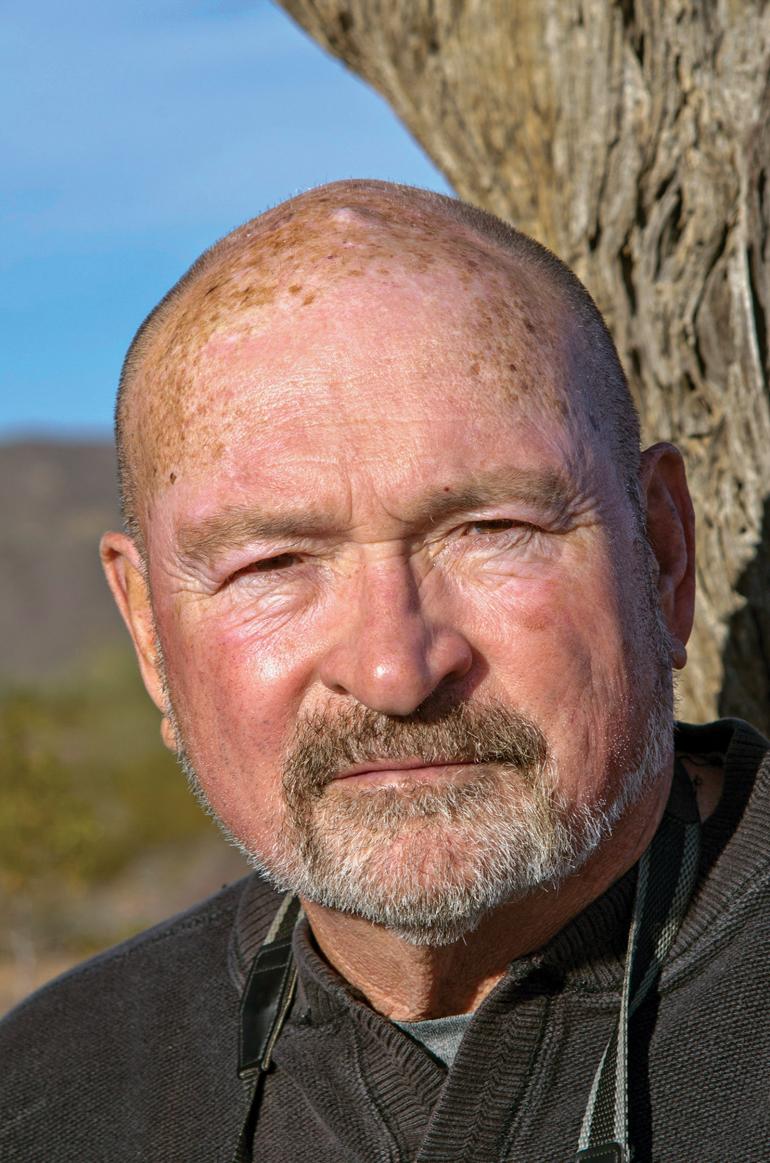

Peacock wears knee-high mud boots, worn-in work pants, and a blue-green fleece sweater with a pin commemorating his service in Vietnam, which he wears to honor “Everyone. On both sides.” Moving gingerly, Peacock explains that he’s recovering from an illness that filled his lungs with fluid. His living room looks out on a windswept plateau framed by the Gallatin Range to the west and the Absarokas to the east. A spotting scope mounted to a tripod points out towards the emerald grass beyond Peacock’s yard, and a pair of binoculars sit on the windowsill. It’s calving season for antelope, and he points one out right away, bedded down just a few hundred yards from his back porch. Peacock has fought his share of battles—for his country, for bears, for wilderness—but not today. It’s a pleasant Montana afternoon, and there are no enemies in sight.

The amount of blood, sweat, tears, and elbow grease Doug Peacock has poured into protecting wild spaces and wild creatures is unquantifiable.

Peacock is one of the most influential conservationists of his generation. He helped popularize a new form of environmentalism that was about standing up for what’s right by any means or method. If cutting fence or disabling strip-mining equipment seemed like the right solution to Peacock, he did it. More currently, Peacock is the leading voice for the protection of grizzly bears in the Lower 48 and the founder of Save the Yellowstone Grizzly. As state governments push to remove federal endangered-species protections for grizzlies, Peacock fights like hell to stop them. The next five years will likely prove to be some of the most pivotal for grizzly bears, and Peacock will speak on their behalf every chance he gets. He can’t do it alone, though, and he can’t do it forever. I’ve known Peacock for a while, and each time we speak, the 81-year-old reiterates a sobering reality: “I have one foot in the grave.”

Peacock grew up in Michigan and explored his local woods and swamps with a burning curiosity for all things wild and ancient. He canoed, hunted, and searched for artifacts left behind by indigenous civilizations, finding wonder in the arrowheads and tools from another world. “All that stuff on the land when I was small directed my interest to things that were intangible to my modern life,” Peacock says. “I wondered, Who the hell were these people? How did they live, and what did the land look like then?”

After college, Peacock was drafted into service in the Vietnam War. While he served his country as a medic in the Special Forces, Peacock carried a map of Yellowstone—a place he had been but hadn’t yet explored to his satisfaction. During long nights in the jungle, Peacock would trace his finger along the map and imagine himself flying over the Park. “When I got back from Vietnam, I just went to the blank spots on the map,” he says.

On Peacock’s first venture into the Yellowstone wilderness in the late ’60s, a malaria infection he contracted in Vietnam struck him with full force. Peacock found himself near a group of grizzlies he assumed were a fever-induced hallucination, but when the fever wore off, he realized that the bears were real. “It was sort of magical,” he says. He decided to stay and observe the bears, quickly gaining admiration for their beauty and grace. Peacock took pains to ensure the grizzlies never noticed him, approaching carefully, staying downwind, and enjoying the bears through binoculars, a camera lens, and his retinas. It was the beginning of a lifetime of fascination.

In the desert, Peacock found both solitude and a deep friendship with renowned writer Edward Abbey. Together, Peacock and Abbey explored the landscape and led a burgeoning civil-disobedience movement in the name of saving wilderness from development and resource extraction.

Each summer, Peacock returned to film the grizzlies; each winter, the bears retreated to their winter dens and he retreated to the lower Sonoran Desert. There, Peacock found wild terrain devoid of humans for hundreds of square miles. Drawn to the subdued beauty of the arid landscape, Peacock completed a series of treks across huge swaths of the desert, refilling his canteen at natural tanks where water collects in unique rock features. “I could walk 160 miles over ten days and carry my own water and never see another human being,” Peacock says. Whether in the Rockies or the desert, Peacock sought out solitude wherever he could find it, understanding that it would become increasingly elusive once he married and had children, which he later did. “Solitude is indeed the deepest well I’ve ever known,” he says.

In the desert, Peacock found both solitude and a deep friendship with renowned writer Edward Abbey. Together, Peacock and Abbey explored the landscape and led a burgeoning civil-disobedience movement in the name of saving wilderness from development and resource extraction. Peacock is cagey about the details of his and Abbey’s antics, but he acknowledges that they had a formative 20-year friendship—and that Abbey based George Washington Hayduke, the iconic troublemaker of his novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, on Peacock. “We learned from each other,” Peacock says of Abbey, who was 15 years older. “There was a paternalistic edge to our friendship, but it was indeed a friendship. We spent a lot of time together, and the value we shared was the value of wilderness,” Peacock says.

When Abbey died in 1989, Peacock prepared the food for his wake. Abbey had specifically requested sheepherder stew, and Peacock decided to get the meat by shooting and butchering a cow belonging to a local rancher who had recently made headlines for killing 17 mountain lions. The rancher claimed the cats were preying on his cattle—which grazed on public land—and posed for a photo with the severed heads of the slain animals. Peacock knew the potential penalties for cattle rustling, but he decided that the rancher deserved punishment. “I intentionally poached one of his goddamn cows,” Peacock says, “and I don’t regret it one bit.”

Peacock’s work on behalf of bears continues out of necessity. Recent efforts to remove Yellowstone and Glacier grizzlies from the federal endangered-species list threaten to open hunting seasons for the bears, and Peacock—a hunter himself, but only for food—fears that trophy hunting for grizzlies would result in a catastrophic population decline. If he’s right, delisting grizzlies may be a grave mistake. “I don’t think they can survive delisting and trophy hunting,” says Peacock, who has put his other work on hold to focus on a film about the bears. “I’m adamant about that. I believe they will go extinct in the Lower 48.”

At 81, Peacock is considering his legacy. “New York will never give a shit about the kind of stuff I care about,” Peacock says, “But I’ve fought for wilderness and wild causes all my life and it’s made a difference in some people’s lives.” The amount of blood, sweat, tears, and elbow grease Doug Peacock has poured into protecting wild spaces and wild creatures is unquantifiable. He devoted his life as few do: by picking a small piece of the world that he loved more than any other and directing all his energy toward protecting it.

Peacock is prone to venting about Montana’s current government leaders and their quest to rid the state of bears and wolves. He chooses words carefully, often seamlessly quoting his own writing as though he has figured out the perfect combination of words to express his point and refuses to articulate it any other way. As he spoke about bears, his frustration melted into warm memories of June afternoons watching grizzlies hunt and play. Peacock is nothing if not fiercely loyal to his wild companions.

Doug Peacock fought for his country, and he continues to fight for its wildlife and its wild spaces. He takes no shit and pulls no punches. He is decisive and he is strong. We would all do well to be a little more like him. When he passes on, his movement will have to march forth without him. In his words, “We have to fight like a sonofabitch. Right now.”

Essential Peacock Books

There are few western writers—hell, few western citizens—as articulate, passionate, and driven as Doug Peacock. Whether fighting for his country or its wildlife (to Doug they’re the same fight), he’s the quintessential “man in the arena.” When he puts pen to paper, transcribing his stories and philosophies, we’d all do well to listen, and listen good. This is a starter list of his best-known works.—the editors

Grizzly Years: In Search of the American Wilderness

After a lifetime observing bears in their natural habitat, Peacock resembles a bruin himself, only with one small difference—he can write. And eloquently so, as he clearly demonstrates in this reflection on bears, wilderness, and war. Holt McDougal; $21.

The Essential Grizzly: The Mingled Fates of Men and Bears

If you want to fall asleep at night, don’t bring this book on a backpacking trip. Not because of the attack stories—although there are a few—but more so because of Peacock’s humbling narrative, in which he argues that big, wild animals are essential to our survival as a human race. Lyons Press; $30.

Walking It Off: A Veteran’s Chronicle of War and Wilderness

After deployment in Vietnam, Peacock returned stateside suffering the mental effects of war, compounded later by the death of his close friend Edward Abbey. His solution? To walk it off. From Vietnam and Nepal to the desert southwest, Peacock walks and reflects on life, then walks some more. Lynx House Books; $19.

Was is Worth It? A Wilderness Warrior's Long Trail Home

Published in 2022, this book is a collection of short stories reflecting on a life in the field. The essays span several decades, giving readers insight into the trajectory of Peacock's thoughts and actions. It's a hefty anthology, accompanied by plenty of colored illustrations and photographs. Patagonia Books; $28.