Do What the River Tells You

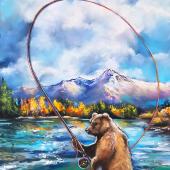

Craig Mathews, co-founder of Blue Ribbon Flies in West Yellowstone, reminisces on a long life on the water—both fishing and working to save the river for future generations.

Craig Mathews approaches the Madison River, rod in hand, but instead of plunging into the current to stalk trout, he sits down and waits. He listens to the slurp and burble of the river. He watches an osprey wheeling high above. He hears the wind sigh through the aspens along the bank.

The river’s trying to tell him something.

He sees a small bug, a caddis, emerge from the water 20 feet from his rod tip, struggling to free itself from a shiny film encasing its wings. Then he sees another, and another, little morsels bobbing up to the surface and floating along for trout looking to snap up an easy meal. He carefully chooses a fly, ties it onto his line, and begins to fish.

“I’m kind of an impatient guy,” he says. “But I’ve learned that if you just sit on the bank, the whole thing unfolds right in front of you.”

Meanwhile, another angler plunges into the river and starts wading up the middle, casting as he goes and switching from big streamers to yellow sallies every few minutes. Eventually he sees the white-haired man quietly fishing to one spot on the bank and comes over to ask what he’s doing. Craig tells him.

After 40 years in Montana, first as West Yellowstone’s police chief, then the owner of Blue Ribbon Flies, and eventually as co-founder of 1% for the Planet with Patagonia owner Yvon Chouinard, Craig has learned to listen. And when he’s fishing, he’s guided by a simple philosophy: do what the river tells you to do.

When Craig moved to Montana in 1979, he didn’t know what he was getting himself into. He’d just accepted a position as police chief of West Yellowstone, and he planned to stay for a year and spend long hours away from work hunting and fishing the nearby Madison River before returning to Michigan where he grew up. But he and his wife Jackie were faced with a jailhouse of hungry inmates the town couldn’t afford to feed, fearsome biker gangs regularly passing through, and only four other cops on the force to maintain order. Juggling these responsibilities, he wasn’t left with much time to go fishing.

“I’m going, holy goddamn cripe what did I step into?” he remembers.

Craig never even expected to become a cop in the first place. He was living with Jackie in Grand Rapids, Michigan with a criminal-justice degree and a year of grad school under his belt after narrowly escaping the draft for Vietnam (they missed him by three numbers) when Jackie suggested they move to Montana for a year.

The two already traveled there each fall to fish, so the proposition was attractive, but Craig’s first reaction was disbelief and skepticism—after all, where would they work? But Jackie called up the West Yellowstone police department then and there and they hired her over the phone as a police dispatcher. Then she handed the phone to Craig, told him it was the police chief, and said he was looking for a replacement.

“You can’t walk in and control a town like West Yellowstone,” Craig says. “There were some times when, oh man, I thought we were gonna lose it. But we never did.”

“My eyes were spinning,” Craig says. “I’m going, Jesus Christ, 10 minutes ago we hadn’t even talked about moving and all of a sudden he’s looking for a police chief!”

But Craig’s always made decisions on a wing and a prayer, and a few weeks later, after a flight to Montana and a brief interview, there was a new sheriff in town.

With meager resources and a tiny squad, Craig knew he’d have to be creative in how he policed West Yellowstone. Biker gangs like the infamous Gypsy Jokers frequently passed through town on their way to Sturgis, and rather than try to control them with brute force he didn’t have, Craig figured he’d have to find ways for them to coexist. He set aside an 80-acre campground eight miles out of town for the bikers to use and began developing relationships with these hardened and tattooed riders.

“I treated people the way I expected to be treated,” Craig said. “I’m not saying we hung around and sang Kumbaya, but we got along, we respected one another, and we didn’t have any blow-ups.”

There were occasional skirmishes. Craig’s teeth are all chipped from being knocked down as a cop, but he would always get up smiling. “It totally disarms people,” he explains. “They go, ‘Either you’re totally insane or I’m in big trouble.’”

Craig made other efforts to work with the town and not against it. He’d have lunch every week with West Yellowstone’s ladies of the evening to get the local scuttlebutt, and when rock groups like Commander Cody and the Lost Planet Airmen or the Amazing Rhythm Aces came to town, Craig didn’t try to police the rowdy concerts. He told the organizers that what happened inside the venue was their problem, and if it spilled into the street, it was his.

He was putting into practice a philosophy he’d heard as a criminal-justice major at Michigan State University: police a town the way it wants to be policed. And it was working.

“You can’t walk in and control a town like West Yellowstone,” Craig says. “There were some times when, oh man, I thought we were gonna lose it. But we never did.”

Their allotted year passed, but the couple didn’t go back to Michigan. Craig was about to make another life-changing decision on a wing and a prayer.

Craig’s sister was born with a spinal-cord defect called spina bifida, and teaching her to tie flies when he was young gave him the idea to start a wholesale fly-tying business that hired disabled people. But it remained only an idea until one September afternoon.

He was on his way to the river to fish when he ran into the local fire chief, Gus, who asked him what he would do once he retired as police chief. Craig mentioned the wholesale fly-tying shop that hired disabled people, and Gus told him he’d be over to his house in a few minutes to talk about it. Eight hours later, they were digging the hole for what would become Blue Ribbon Flies.

The shop started out wholesale, with Craig hiring disabled people as well as local and federal prisoners as tiers (he once discovered that a man he’d jailed was an excellent fly tier, which gave him the idea to put prisoners on work release; they said it made the time fly by and it also saved taxpayers money). When Bud Lilly’s famous Trout Shop in West Yellowstone closed, Craig decided to open a retail shop, too.

Craig’s known for developing several famous patterns himself, including the sparkle dun, x-caddis, and nature stone nymph, and soon after starting Blue Ribbon Flies, he wrote his first book, Fly Patterns of Yellowstone, which he would follow up with Fishing Yellowstone Hatches, The Yellowstone Fly-Fishing Guide, Western Fly-Fishing Strategies, Fly Fishing the Madison (co-authored with Gary LaFontaine), and Simple Fly Fishing (co-authored with Yvon Chouinard and Mauro Mazzo).

Business was booming in the ’80s and ’90s, but Blue Ribbon Flies quickly became about more than that. With more and more people flocking to the Madison to fish, the river was trying to tell him something—if anglers and recreationists like Craig didn’t act to protect it, it would be lost to future generations. Craig was listening.

Over the last few decades, Craig has become known as a champion of conservation. He and Jackie have sat on the boards of various conservation groups—the Montana Nature Conservancy and the Yellowstone Park Foundation (now Yellowstone Forever), among others—and they’ve received numerous awards, including the Lee Wulff Award from the Federation of Fly Fishers and the Protector of Yellowstone National Park, the most prestigious award a national park can give.

Many of his and Jackie’s most notable efforts have been right in their back yard on the Madison. Craig and Jackie helped facilitate the purchase of lands surrounding Three Dollar Bridge, a popular access site on the Madison River that was going to be sold and subdivided, ensuring that public access would be protected for generations to come.

“This river has given me so much pleasure, as have all the rivers in Yellowstone Country, and I just want to see that continued,” Craig says. “You know, I’m selfish. I’m selfish about my time on the river. But doggone it, young people deserve a healthy river. And that’s what I’m working for right now.”

But his conservation work extends far beyond the Madison Valley. Arguably Craig’s greatest achievement was co-founding 1% for the Planet, a global network of thousands of businesses and environmental organizations that donate at least 1% of their annual sales to a certified conservation cause. To date it’s raised over $650 million for conservation. He and Yvon Chouinard, the founder of Patagonia who Craig met one day when he came into the shop demanding to know why Blue Ribbon Flies didn’t stock his brand, dreamed it up one afternoon fishing on the Madison, driven by a mutual desire to protect the resources they got to enjoy and respond to the needs of a warming and increasingly developed world.

“We’re right on the very edge, we could lose this whole thing,” Craig says. “We could lose this river, we could lose this planet, we could lose this little place we call home—our world—if we don’t address all the stinking pollution and all the carbon issues that we have.”

Craig says that the world is trying to tell us something right now, and we need to do as it says.

Craig has taken a step back now that he’s retired—he sold Blue Ribbon Flies in 2014 and he and Jackie have stepped down from many boards of directors—and now he’s listening to new, younger voices that want to make change. He believes young people will save the planet once the “white-haired guys” step aside, and he’s done his part to make that happen.

With his time on the front lines mostly over, Craig spends his days with Jackie at their house in Sun West Ranch south of Cameron, hanging out with Gizmo and Dozer, their two German shorthairs, and hosting friends like Yvon who come through town. And every year, he still fishes over 150 days and ties thousands of flies.

“I always tell people, I’m the luckiest guy in the world to be here,” he says. “I could be some frickin’ prosecuting attorney back in Kent County, Michigan or somewhere, and maybe I would have had a good time doing that. But I’ve had a great run. In the almost 47 years we’ve lived here, I wouldn't give up a second of it for anything.”