Conservation Takes Flight

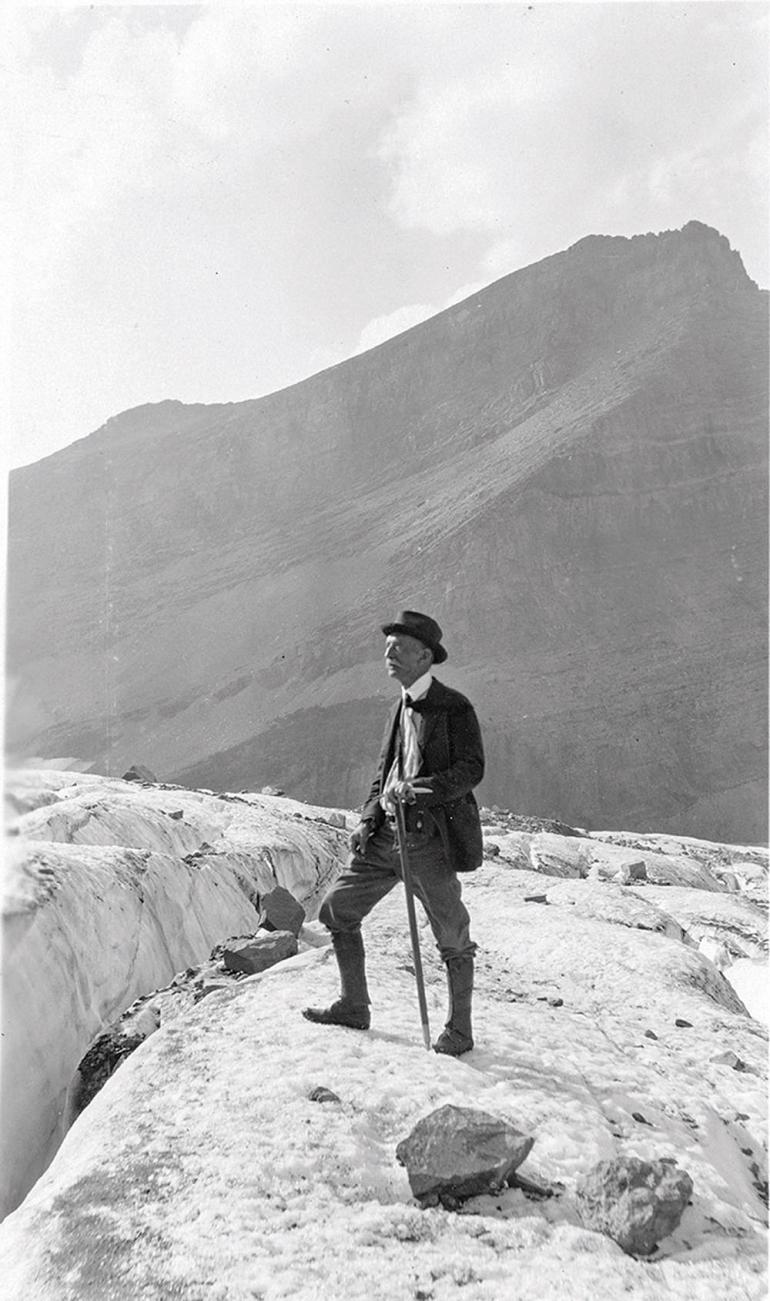

The life & legacy of George Bird Grinnell.

The tracks of many explorers, conservationists, and ethnologists have passed through southwest Montana. Countless people have scaled the same mountain peaks, stood on the same riverbanks, and admired the same stars. Look closely at those tracks, however, and some truly remarkable people stand out. Among them is George Bird Grinnell.

Born in 1849, Grinnell grew up along the banks of the Hudson River in New York. From a young age, he had a strong affinity for the natural world, and was infatuated with fishing, hunting, mammals, and (you guessed it), birds.

George Bird Grinnell is known as “the father of American conservation,” and for good reason.

Grinnell attended Yale, but he wasn’t fond of academics and could often be found rowing the river, taking long walks, or wandering under the light of a full moon. After university, Grinnell chased the mystique of the West, partaking in paleontological expeditions from the plains of Wyoming and Utah to the Black Hills of South Dakota.

In the Spring of 1875, Grinnell joined Colonel William Ludlow on a geological survey in Montana. They traveled through Helena, Camp Baker, and Fort Ellis, then continued south to Yellowstone. Grinnell documented the natural wonders of Yellowstone, but also witnessed the deliberate and unrestrained killing of wildlife for their hides alone.

Shortly after his Yellowstone visit, Grinnell became the editor of Forest and Stream magazine—which would later become North America’s leading natural-history magazine. Busy developing the bones of the publication, Grinnell didn’t make it west again until the early 1880s, but used his newfound voice in the interim to advocate for conservation efforts there.

In doing so, he founded the National Audubon Society in 1886 to protect songbirds and the smaller avian species of North America. He was also a founding member of the Boone and Crockett Club in 1887, alongside the likes of Theodore Roosevelt. The two men campaigned for fair-chase hunting while admonishing certain types of traps and other tactics they considered unethical. A few years later, thanks to their efforts, the Lacey Act was passed, protecting birds and mammals within Yellowstone Park’s boundary from hunting.

In addition to wildlife, Grinnell was fascinated with Native Americans, and used his influence to share and document the culture of the Pawnee, Gros Ventre, Blackfeet, and Cheyenne tribes. He got along well with their elders, was given tribal names, became fluent in the language of the Blackfeet, and was even made an honorary chief. He advocated for the prosperity of Native American culture and worked with tribes and the U.S. government to create a mutual understanding among both groups.

George Bird Grinnell is known as “the father of American conservation,” and for good reason. Next time you see a bison herd roaming through Yellowstone, hear a robin sing at dawn, or take a trip north to Grinnell Glacier in the eponymously named national park, give a quick nod to the people like Grinnell who came before us. They weren’t after the money or the fame, but rather the preservation of the natural world and the cultures and wildlife we all share it with.