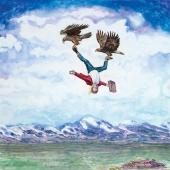

Lost in Space

Preserving the true spirit of adventure.

Before heading into the woods, I usually tell my emergency contact that if something bad happens, I’ll crawl to the nearest creek bottom before I die. I’ll drag my mangled leg, punctured lung, or feverish body downhill toward the sound of water—crawling on all fours (or threes, or twos if I must) to reach it. Much to my mom’s chagrin, it’s only partially a joke. But, realistically, it’s a half-decent strategy. If search-and-rescue were to come looking, all they’d have to do is walk the creek bottoms to find my body. And they’d probably find some other cool dead stuff while they were at it. In the forest, almost everything goes to water to die.

Typically, my contact is a friend or coworker, sometimes it’s my brother, occasionally a buddy in Wyoming (who I give a 50-50 chance would actually come looking for me), and once, as I quickly discovered was a grave mistake, my mother.

It’s not that I’m morally opposed to sending loved ones a note, but there’s something about self-reliance in the woods that I find rewarding.

“What could possibly go wrong?” she asked, after I’d laid out plans for a solo, off-trail trek through the Beartooths.

I began rattling off a laundry list of possible afflictions: “Well, let’s see. I could break a leg crawling over deadfall, get brutally mauled and gored by a grizzly, contract giardia and die of dehydration, fall off a cli—”

“Enough!” she cut me off, covering her ears with her hands. “I don’t want to hear it!”

“Okay, but you asked,” I said.

“Can I at least buy you an inReach?”

No, I insisted, I did not need or want an inReach, sat phone, Spot tracker, or any other kind of communication device. People have been doing without them for thousands of years, I explained, and been just fine. Could Lewis and Clark text home every evening, reminding their loved ones that they still existed, and giving them an update: Honey, today we shot 47 deer on the upper Missouri, and had a close run-in with a female grizzly bear. Would said loved ones have found that comforting?

It’s no different today. Does my mom need to know that I saw a whole pack of wolves—and then decided to call them in to a few hundred yards? Does she need to know about that slippery log jam I used to cross a raging spring creek (oh, and that it was right above a man-swallowing rapid), or the time I sprinted back to camp in a freak spring gale, dodging full-grown trees sailing like balloons? No, she does not. And if she hadn’t asked in the first place, perhaps she wouldn’t even be worried!

It’s not that I’m morally opposed to sending loved ones a note, but there’s something about self-reliance in the woods that I find rewarding. When a boat breaks down in bear-infested country 40 miles away from help, you figure out how to fix it, or you perish. And when your partner takes a scary swim, you drag ’em out, dry ’em off, decompress, and get on with it. It’s the same reason people have been going on adventures for centuries, and it’s in those moments that you become stronger, more capable, confident, and self-assured. And better yet, by the time you get home to the comfortable, comforted world, those same stories have had time to steep, morph, and aggrandize into thrilling tales, making them all the sweeter to regale friends and family with, days or weeks after the fact.

This summer, I’m heading into the Bob Marshall for a couple weeks, and trust me, you won’t be hearing a darn thing from me ’til I’m on the road heading home. Sometimes, just sometimes, no news is good news.