Whose Elk Are They?

A growing imbalance in the management of Montana's wildlife.

Wildlife management in Montana is currently facing radical revision, upending a series of valued precedents: the primacy of biology in decision-making, management by wildlife professionals, established regard for resident hunters, and respect for the public-trust doctrine. Although the current crisis focuses on elk, our iconic—and most commercially valuable—big-game animal, policy changes could eventually apply to trout, game birds, and every other wild species capable of making someone a buck.

Changes initiated over the last year now lie somewhere between a mess and a disaster, mainly for Montana residents of ordinary means. Given this target-rich environment for outrage, I’ll narrow the focus to a pair of examples: first, providing bull-elk tags for nonresident landowners outside of customary channels; and second, the pending lawsuit against the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) filed by the United Property Owners of Montana (UPOM). Then we’ll look at broad implications for the future.

Responsibility for management of fish and game resources belong to the states both by precedent and statute. Most states make more licenses available to resident hunters and anglers whenever the balance between supply and demand requires restricted opportunity. Though some wealthy nonresidents and commercial outfitters have long opposed these polices, they have consistently withstood court challenge. And why not? Residents are the ones who pay the taxes, maintain the infrastructure, and—particularly in western states that offer the best hunting—earn below-average wages. For many of us, enjoying the wildlife resources is compensation for putting up with such disadvantages just to live here.

In Montana, the current push to overturn this principle is driven by two forces: commercial outfitters and wealthy nonresident landowners. Limiting nonresidents to a percentage of available tags in limited-draw areas restricts commercial outfitters’ opportunities to offer high-dollar trophy hunts to out-of-state clients. Much of the private land in Montana is now owned by nonresidents, a trend we have all seen accelerate recently. Many of these properties are large ranches purchased for their value as hunting properties, not agricultural operations. Many new owners have money, political influence, and the right to close their property to public hunting; they have everything, that is, except the ability to acquire elk tags like residents. Most are careful to avoid staying here long enough to incur resident tax obligations.

Of course, if those elk tags were really that important to them, they could become residents, pay some taxes, and put up with Montana at 20 below. That idea has had very few takers.

Money and political influence have provided a solution to their problem: Texas-style private ownership of wildlife, in violation of the Public Trust Doctrine and the Montana Constitution (Article IX, Part IX, Section 7.), as advocated by several nefarious, well-funded organizations. Voila; the 454 elk tag.

Many new landowners have money, political influence, and the right to close their property to public hunting; they have everything, that is, except the ability to acquire elk tags like residents. Most are careful to avoid staying here long enough to incur resident tax obligations.

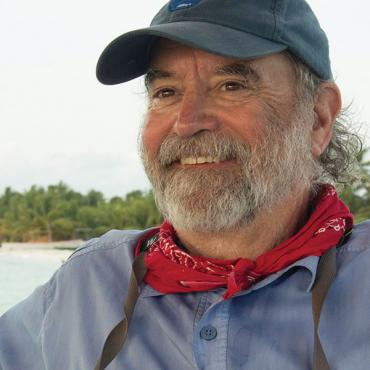

The history of this program is long and complex, and readers interested in more details should see Andrew McKean’s excellent summary “Bulls for Billionaires” in the May 2022 issue of Outdoor Life. In brief, legislation enacted in 2001 ostensibly intended to increase hunting opportunities for resident hunters, offered landowners bull-elk tags in return for allowing a small number of public hunters access to their property to hunt. The plan received little attention until the Wilks brothers, Texas billionaires who purchased vast tracts of prime elk habitat in central Montana, decided that their wealth entitled them ipso facto to expanded trophy-bull hunting on their property. I lack the space here to review their other transgressions against the common good.

Toward the end of the 2021 legislative session, regulatory changes made it easier for landowners to acquire more bull tags. But the Wilks’ ranch lies in hunting district 411, which has always required residents and nonresidents alike to draw hard-to-get permits to hunt elk there. When they failed to draw permits, their attorney negotiated a deal after the drawing that resulted in multiple Wilks’ family members from Texas receiving bull tags that some local residents had been unsuccessfully trying to draw for years.

Is it reasonable for private parties who don’t allow public hunting to expect the state to solve their excess-elk problem?

The reaction from resident hunters was predictable outrage, not that anyone in Helena or Texas seemed to care. Granted, a few dead bull elk from an off-limits property in an area with an (apparent) over-abundance of elk doesn’t represent a biological crisis, but it sets a horrible precedent of allowing the wealthy to purchase wildlife that belongs to the public. Organizations like the Utah-based Sportsmen for Fish and Wildlife (“Ranching for Wildlife” advocates) and Bozeman’s own Property and Environmental Research Center (under the rubric of “habitat improvement”) have spent years, and lots of money, promoting the commercialization of game in defiance of principles that have guided America’s widely admired wildlife policies for decades. These groups have enjoyed some success in states like Utah and New Mexico, and no one doubts that they would love to add Montana to that list.

Now, on to the UPOM lawsuit. The rambling complaint begins by pointing out that the Missouri River Breaks elk herd is well over (arbitrary) population objectives and harming some farm and ranch operations in the area. Both these points are true, but conflicting opinions arise on how this problem arose and what should be done about it.

The suit blames the defendants for failing to manage outdated elk-population goals that were never critically reviewed. In fact, it is impossible to manage a large, mobile animal population distributed over varying types of land in close, interlocking proximity: public land that receives heavy hunting pressure; private land open to some public hunting, which receives modest hunting pressure; and private land managed for trophy bulls, which receives little hunting pressure and is insufficient to reduce elk numbers. It just can’t be done. The suit also protests FWP’s policy of considering “social” factors in management decisions, although that is just what resolving these land-use contradictions requires.

The suit also complains that FWP “forced” private landowners to allow public hunting, which is simply untrue. FWP has never forced private landowners to do anything. Is it reasonable for private parties who don’t allow public hunting to expect the state to solve their excess-elk problem? Voluntarily allowing some public hunting would be a far more effective means of controlling elk numbers than blaming FWP for factors beyond their control.

Plaintiffs complain that FWP is failing to meet statutory obligations to reduce elk numbers. No policy requires the state to remove unwanted elk from private property. The legitimate depredation complaints aren’t elk number problems so much as elk distribution problems. Reduced hunting opportunities on private land increase hunter pressure on public land, in turn displacing elk onto agricultural properties that don’t want them. Properties managed for a small number of trophy bulls become havens, which elk can leave every night to eat neighbor’s crops. To reduce numbers of any ungulate population, harvesting females, not mature males, has proven more successful.

If reducing excess elk numbers is really UPOM’s goal, why did they sue (successfully, to the everlasting shame of the court) to close established access to a huge tract of public land swarming with elk? Answer: so the outfitter at the heart of the matter could offer his clients exclusive access to an area teeming with trophy bulls.

Regulatory changes that would have once been unthinkable in a state that values elk, as Montanans do, have already been enacted with the goal of reducing elk populations, in the form of “shoulder seasons” that create radically expanded opportunities to harvest elk in districts with over-objective elk numbers. In some parts of Montana, it’s now possible to hunt elk from August into February, allowing hunters to kill pregnant cows in winter—if, of course, the hunter can find a landowner who allows hunting.

These policies set a horrible precedent of allowing the wealthy to purchase wildlife that belongs to the public.

Another worrisome argument emerges from the UPOM complaint when plaintiffs allege that FWP has exceeded its authority and only the legislature should be authorized to determine hunting regulations. Virtually every state in the country assigns these responsibilities to wildlife departments staffed by trained professionals. Legislators with no background in wildlife biology and susceptibility to political pressures make poor substitutes and have (or should have) more pressing items on their agenda.

After a sustained attempt at deflection by making the suit appear to be about agricultural depredation, the complaint eventually arrives at its real purpose: ending limited-drawing permits in certain trophy areas, which would provide outfitters with more bull tags for wealthy out-of-state clients. Thus, we circle back to the crux of the matter as outlined earlier: the commercial exploitation of public wildlife by private interests.

Although turning wildlife into commodities may be the most egregious idea to emerge from the current crisis, it’s hardly the only one. Other stinkers include tossing informed wildlife biology out the window, transferring regulatory authority from professionals to politicians, and letting wealthy nonresident interests override the concerns of Montanans. Furthermore, the process by which many of these changes were enacted raises serious questions about transparency in the legislature.

Follow the slime trail back far enough through this fiasco and you will eventually arrive in Helena. Both the governor’s office and the last legislature clearly proved their willingness to throw their own constituents under the bus. During the next election cycle, we can expect to see the usual television ad spots showing the worst offenders posturing in hunter orange and trumpeting their records on “access.” Don’t buy it without looking at the record.

Finally, we arrive at what may be the biggest question of all. Resident hunters and anglers make up a huge political demographic in Montana. Why do we continue to elect politicians clearly aligned against our best interests? I can’t satisfactorily answer that complex question myself and won’t even try here. Maybe next time.

Make no mistake: this crisis involves far more than elk hunting. Whose elk are they, anyway? “Whose state is it, anyway?” might be the better question.