The Big Picture

A call for connection with the life and landscapes of southwest Montana.

It’s seldom as it seems. The river is low and clear, giving cover to feeding trout which are not supposed to be active, yet we still lay a fat grasshopper fly on the surface, hoping for the best.

Or, the weather forecast warns of severe thunderstorms and yet the afternoon breezes by displaying dark cumulus clouds but no turbulence, yet.

Or, nearby, a riding horse hired for a backcountry camping trip, guaranteed to be steady and easy to ride, bucks the tourist off, spooked by a rattler.

The mountain West is not intentionally capricious; it’s simply unpredictable, and we locals like it like that. Mostly.

Many of us accept risk, except when our community stability is rattled by risky change, when we are told that “progress” and “prosperity” and “growth” and “rising real estate values” will give us a better community which, of course, depends on how you define “better.” Is what Bozeman is becoming “better” than what it used to be? Is Jackson Hole? Teton Valley? Livingston? Red Lodge? And who is calling the shots?

What we’re facing are not issues that can be fixed by engineers installing more roundabouts, or haphazard piecemeal attempts at addressing the lack of affordable housing, or natural-resource planners who claim the answer to addressing overcrowding problems on the Madison is by creating float times like you might arrange tee-times at a busy golf course.

I’ve been musing more often of late about why more people want to be here now than 20 years ago, and I’m wrestling with the enigma of how, when destinations become popular, they quickly start to shed the luster that existed before the great hordes arrived.

This isn’t me saying “now that I’m here, lock the doors;” it’s more that I’m psychologically intrigued by what’s causing locals, who have had enough in now-bustling Greater Yellowstone towns, to leave.

What are the values of those who are replacing them? Do they have an appreciation and respect for the caliber of wild country they are choosing to inhabit? If growth means sending longtime citizens heading for the exits, I think there’s a problem.

This is an important community topic, but it is not being discussed in any serious, ongoing public way by town councils, county commissions, or other entities who make the decisions that are, in part, creating the problem by what they are or are not doing. They are in reactive mode. The exodus of locals is also a topic that we almost never see discussed in local newspapers.

Are newcomers coming for wildness that they then desire to tame?

Are they here because it’s the trendy place to be, yet know little of what this place is—and don’t realize that its charm was in not aspiring to be trendy?

Are they enamored by the opportunity to buy local produce from farmer’s markets, but have no idea where the water reaching their taps comes from?

Are they drawn to our valleys because of the pastoral open space, yet won’t hesitate or reflect for a second on what is lost when they build their dream home or subdivision right in the middle of it?

I know it’s rare for a psychological therapist to write about community. But what we’re facing are not issues that can be fixed by engineers installing more roundabouts, or haphazard piecemeal attempts at addressing the lack of affordable housing, or natural-resource planners who claim the answer to addressing overcrowding problems on the Madison is by creating float times like you might arrange tee-times at a busy golf course.

We need to start having a different kind of community conservation that cannot happen through existing collaborative processes or bureaucratic public-comment periods in which people who dwell in cubicles collate “input,” then lay out options that conform to their own biases. And, I would argue, instead of treating places as a menu of items to graze from, we might step back and really ponder what makes them special.

Regular campsites at hosted campgrounds, if you haven’t heard, are booked full these days, like reservations at a fancy New York City restaurant staked out six months in advance.

Our landscapes of mythic, raw individualism host a panoply of options for guests, multi-generation residents, and true Montana Natives, the latter an allusion to the paradox of pride expressed on a bumper sticker. Ironically, those who attach the slogan to their vehicles don’t often reflect on how their ancestors displaced people living here hundreds (or thousands) of years prior.

However we came to the Rockies, whenever we came—be it 30,000 years, 10,000 years, or two days ago—our mountains today have borne witness to human folly ever since. We thought first of how to monetize our entry into the cathedral rather than humbly acknowledging that the cathedral already existed.

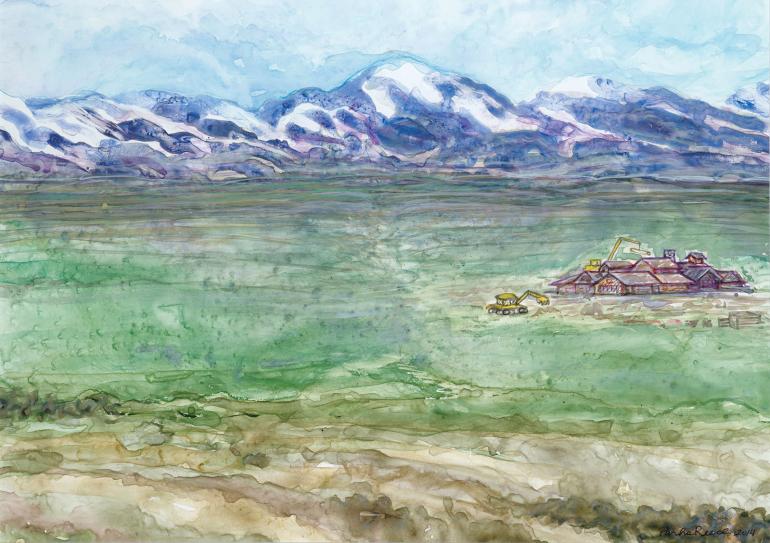

For the first time ever in many corners of Greater Yellowstone, we humans are arguably poised to leave our valleys far lesser places in terms of their power and allure than how we found them. I projected this thought onto Mt. Cowan in the Absarokas as I drove down Paradise Valley to fetch our pull-behind camping trailer tucked into a fishing access campsite at Loch Leven.

Regular campsites at hosted campgrounds, if you haven’t heard, are booked full these days, like reservations at a fancy New York City restaurant staked out six months in advance. The scene at campgrounds and boat put-ins on rivers during the Fourth of July and holiday weekends is, from the view of many, unprecedented and gut-wrenching.

Many locals I know are stunned.

What we are serving up in the Northern Rockies is beauty, and it’s becoming increasingly reserved for guests (thankfully, my daughter-in-law jumps on the reservation system at 12:01am six months in advance of the days we want to stay at a local campsite in the Gallatin Valley).

The kinds of disruptions are multitudinous. Have you experienced the traffic in Yellowstone Park or Gallatin Canyon or Jackson Hole lately? Have you heard about the vandalism to signs up Hyalite Canyon and the Hyalite Reservoir?

Fishing access sites are first-come, first-served, don’t have campground hosts to maintain decorum, and don’t enforce civilized quiet hours between 10pm and 6am. I knew that was true, but when I called the Park County Sheriff on duty at midnight to ask for a drive-by check to enforce quiet hours, she responded from what seemed like a well-worn script: “There is no noise ordinance in Park County. This is not a law-enforcement issue. It is a management one.”

So, is the implication that I have to get in a brawl with Mr. Generator Guy running his $250,000 RV before succor arrives? Nah, I’ll just seethe myself to sleep. But it ought not be like this. We are creating problems for which management might not be able to provide a fix.

Is it just me or have we lost a lot of common courtesies in the desire of some to make our towns as busy as possible?

I guess that is why those who know me well call me a Puritan Radical. Peace and quiet seem to grow in importance as we age. Left to our own resources, as unbridled Westerners who would rather not be treaded on by fancy laws that govern human behavior, we submit to the inconsiderate option of alleged “freedom,” draped in American flags and calibrated to the lowest common denominators of inconsiderate fellow citizens.

Maybe that is why European countries who suffered the depravity of human capacity that was demonstrated in world wars chose to rein in our collective dark side and engineer social democracy as a method of protecting the greater good from ambush by nonage behavior.

What I am conveying is that sans the ethic of caretaking each other and our beloved Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho, we are skidding towards the junkyard of disposable modernity.

When not seeking (non-) peace and quiet in nature, I am content to retreat to our cedar-shake passive-solar home in Bozeman that is protected by a steel fence, plants, perennials, and pines. I am grateful that we moved into this property over 30 years ago and that my wife has a talent for natural landscaping that is a reliable refuge.

I suppose it is our later years that contribute to this retreat. We have had our day in these majestic mountain valleys. I am not registering regrets nor spoiled annoyance at newcomers since I was one too, 40 years ago.

What I am conveying is that sans the ethic of caretaking each other and our beloved Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho, we are skidding towards the junkyard of disposable modernity.

Speaking of junkyards, though, maybe you have seen metal boneyards on the rural landscape where retired cars, trucks, tractors, trailers, and other metal monsters are left to decompose? Rather than the salvage yards in urban landscapes where the dead machines are crushed into rusty cubes and shipped off to be reborn, we here in the West have a tradition of sending all matter of retired content out to pasture, gully, draw, or back-forty.

One such unholy metal junk retirement community sprawled until recently near Chico Hot Springs at the foot of Emigrant Peak, its majesty visible from Loch Leven campground. How did ugly find a home in paradise? And looking back, was it a bad thing?

The real question, now that the eyesore is gone and might be replaced by a new subdivision of homes that would be marketed as allegedly “affordable,” is which human construction detracts from view and place—which represents a bigger negative impact on wildlife trying to pass through and, after that new permanent subdivision goes in, what’s next?

Turns out, the value of eyesores is sprawl-repellant when you need it.

Incremental adaptation to rising temperatures in a way contributes to the ultimate crisis because it allows us to deny moment by moment what is happening before our eyes.

Yes, we have come to a cultural and planetary fork in the road. The divisiveness of our personality politics, rife with disinformation platforms, is symptomatic of our juncture in history. If individual consciousness is representative of the greater whole, then the troubles of clients I hear in my private practice speaks to an emerging citizen rattling and ultimately, a reckoning.

As I’ve said before, people are anxious, and local people are feeling unsettled by the change. The insurance claims I submit for my clients are typically one of three diagnoses: generalized anxiety, adjustment, or mood disorders. What drives these disorders has changed over time.

Once upon a time, a common anxiety in Bozeman was worrying about personal finances and retirement, but now it’s an inability by many locals to find affordable housing—or any at all.

A gauge of the capacity we have as a species for perceptual change is said to be that we will not fundamentally change how we perceive reality until and unless our perceptual matrix of stability no longer works at all. It’s analogous to the frog in a pot of warming water.

Incremental adaptation to rising temperatures in a way contributes to the ultimate crisis because it allows us to deny moment by moment what is happening before our eyes. This point was driven home when I met a neighbor last spring who was on his bike leaving for his job as a professor at MSU, and I was beginning my walk down to my office. He remarked about the record-breaking Phoenix-like temperatures in Canada and a town engulfed in flames. He then invoked the famous frog-in-the-pot analogy. “When you slowly raise the temperature on the water in a vessel where a frog is kept, it adapts to the increasing temperature.”

I pitched in saying, “Until he jumps out.” And the neighbor replied, “No, he stays in until he dies.”

I am now reminded of the Indie rock group R.E.M.’s song released in 1987, entitled: “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (and I Feel Fine).” I enjoyed the irony of this lyric when it was first released, and now we live this paradox as a global reality. We are tasked with finding meaning, love, peace of mind, and beauty in the Anthropocene.

How do we accomplish equanimity for fellow humans and other beings when we are so detached from reality? Indigenous people can tell us about change; they’ve already endured the nightmarish transformation of place in the West that non-natives cannot imagine.

So what is the answer? We must find a way to exert a presence of dignity, forthrightness, clarity, non-reactivity, support of wise policy-makers, and embrace a joy that transcends circumstances which require us to confront unpleasant challenges. Together, we are frogs in the pot. Unless we find a way to have a new kind of dialogue about community, we will not achieve what we desire to be, and we will not feel fine.

Timothy Tate is a professional psychotherapist who has practiced in Bozeman for 42 years. This essay was originally published in Mountain Journal.

For more reading about New Bozeman, check out another essay by former mayor Steve Kirchhoff.