Easy Does It

Like many outdoor towns, Bozeman is being loved to death. But there’s a solution: transform our passion for the great outdoors into a force for its protection.

I’m walking my pup in the sagebrush hills east of Gardiner at the edge of Yellowstone Park. Suddenly he bolts—hot on the trail of a terrified mule deer and her fawn. I shout, scream, and plead for him to come back. But in a flash, he disappears over a rise. I’m certain that I will never see him again—brunch for a hungry wolf or coyote. Then, miraculously he reappears, panting and wild-eyed. I knew that punishing him would be counter-productive. But I vow that this will never happen again. Within a week he is sporting a shiny new shock collar. And I have been trained on how to use it. Problem behavior, his and mine, solved.

How We Got Here

That incident got me thinking about the impacts of my outdoor recreation pursuits on wildlife and wild places. The more I pondered it, the more concerned I became. Despite being a card-carrying environmentalist, I realized that on occasion, and maybe often, I was inadvertently harming the very entities I love.

How could this be? Outdoor recreation was supposed to be the environmentally-sensible alternative to natural-resource extraction. And I should know. I was one of the people promoting that idea back in the early 1990s when this region was under assault by the oil & gas, timber, and mining industries. It would have been politically unfeasible, not to mention unethical, to advocate an end to these destructive practices without offering an economic alternative. Outdoor recreation seemed like the perfect substitute. It was growing in popularity. Its environmental impacts seemed minor and easily mitigated. And we in the conservation movement were diehard hikers, bikers, boaters, hunters, anglers, climbers, etc. If we liked it, it must be good.

Fast-forward 30 years. The Bozeman area is now widely regarded, and deservedly so, as an outdoor-recreation mecca. It is often included—for better or worse—in someone’s Top Ten list of best towns for outdoor lovers. Recently, however, it’s also been in the headlines (New York Times, Mountain Journal, Montana Outdoors, Bozeman Chronicle, to name a few) for something far less flattering. We’ve become the poster child for what happens when the intensity and character of recreation on public lands and waters begins to degrade those very resources.

The summer of 2020 will be remembered for many things—very few of them good. And one that was particularly evident was the crush of people using trails, campgrounds, rivers, and river-access sites. Yellowstone Park, for example, received its highest number of fall visitors ever. Meanwhile in the Bozeman area, except for some of the best-kept secrets, chances are you were not alone while recreating. In fact, you were probably in a crowd. Which, I would guess, is exactly what you were hoping to avoid.

Conservation Challenge

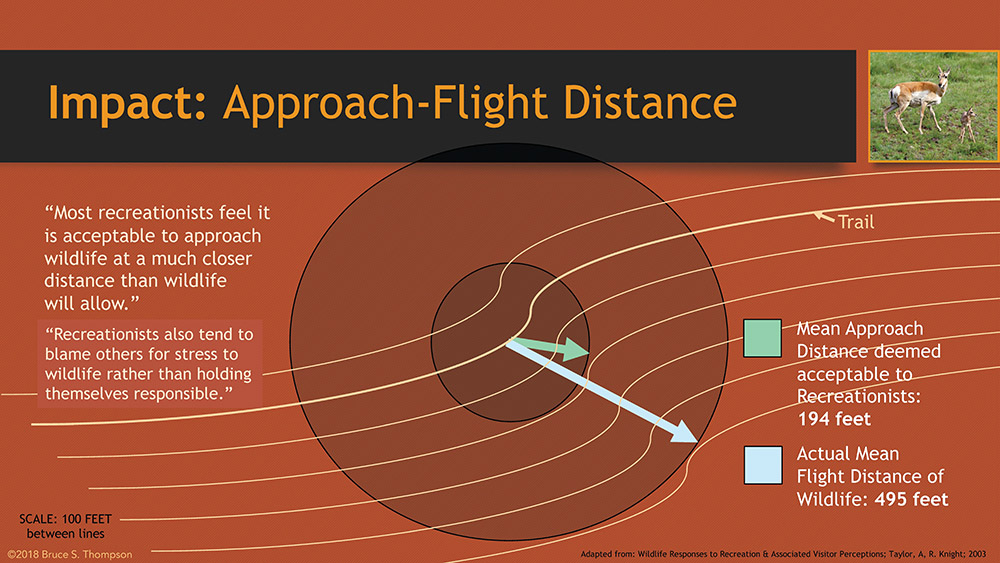

Those favorite trails, along with our rivers, parks, and recreation facilities, are beginning to show the strain of this unprecedented use. While that may be affecting the quality of our outdoor experiences, more importantly our unique wildlife heritage is also affected. Recent studies have documented these impacts on everything from elk to wolverines. As an example, the construction of new trails in particular is proving to have significant negative impacts on multiple species.

There’s also this little-understood concept of “cumulative effects.” By comparison, let’s say you haven’t been sleeping well. You’re stressed out from work, the sink is plugged up, and then someone dings your car in the grocery-store parking lot. You snap, and it isn’t pretty. Something similar is happening to our critical wildlife habitats. Climate change is subtly but significantly altering them. Nearby development is severing the historic ranges. And seemingly overnight, new trails slice into them, followed by hikers, bikers, dogs, and a lot more human activity. An already stressed system starts to unravel.

These cumulative effects are growing exponentially as our region’s population explodes. I say exponential because someone who moves here most certainly has a higher propensity to recreate than does, say, someone moving to Des Moines. And rapidly-evolving technology, such as electric bikes and GPS devices, makes it easier to go faster and deeper into wild country.

All Things in Moderation

So, what can be done? We aren’t going to quit recreating, nor should we. Being in the great outdoors is a major reason why we all live here. It’s healthful, therapeutic, intellectually stimulating, and damn fun. It’s a godsend.

Like many other environmental problems, the solution is more about being willing to, at times, change our behavior and practice the lost art of restraint. And in more expansive terms, to continue to evolve and grow as human beings who recognize that we are incredibly fortunate to live in such a spectacular place, but that we are also its caretakers. At least until we pass it on to future generations.

Ten Ways to Transform Recreation into a Force for Conservation

1. Know Thy Ecosystem. The more we comprehend why people do what they do, the more apt we are to get along with them. Recreationists and public-agency staff would benefit from better understanding what makes these wild ecosystems tick. This is especially important in places experiencing intense recreation pressure. Ecological knowledge should inform how we develop, manage, and engage these landscapes. Look at it as relationship counseling for public-land users.

2. Tread Lightly. We’ve come a long way in cleaning up our recreational practices on both land and water. This includes things like where we set up camp, how we dispose of our garbage, and what we do with our waste. Learn these practices. Diligently apply them.

3. Don’t be a Trailblazer. DIY trail-building has become all the rage. But it’s incredibly destructive and disruptive to wildlife. Always remember, “access” is not conservation. In fact, new access and trails can undermine conservation values. Try to stay on existing trails. And embrace the fact that the wellbeing of many wild creatures requires that we give them space.

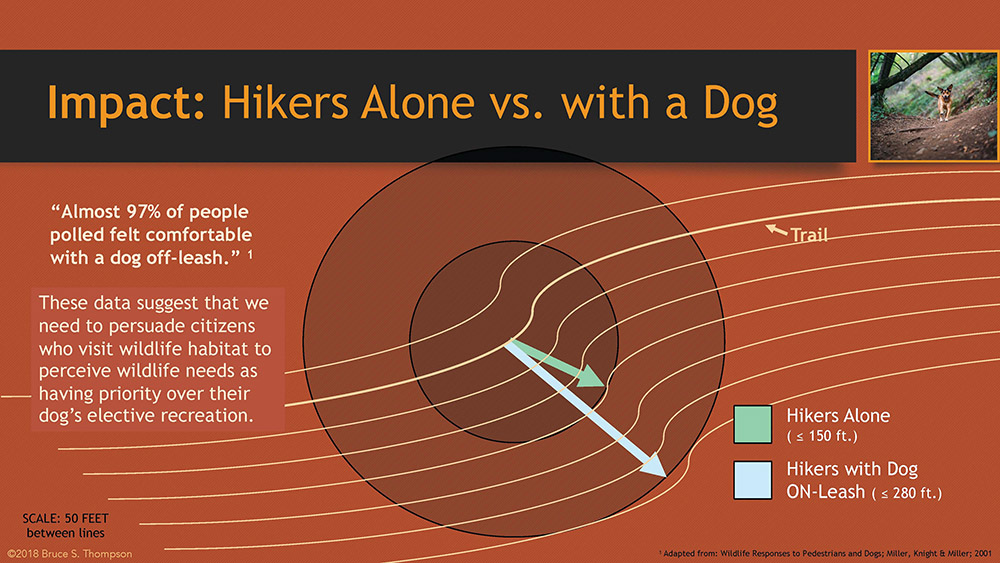

4. Control that Pooch. Dogs are the sacred cows of the northern Rockies. And it’s not surprising that people want to take their dogs with them just about everywhere—especially when we hike, ski, or bike. But uncontrolled dogs can pose serious threats to wildlife, and even to people, when their dogs provoke wildlife attacks. Use of a leash or shock collar can alleviate or reduce these impacts. And always, always, pick up after your dog. Our gin-clear streams will thank you. Finally, while it may be hard, consider leaving your pup at home when venturing into sensitive wildlife habitats such as wetlands or grizzly country. It’s the right thing to do.

5. Advocate for Protection. Every Bozeman outdoor enthusiast should be a strong advocate for resource protection. That means more than just sending a check to conservation groups demonstrating a serious concern for these issues. It means learning about resource-management challenges and weighing in on them. The Custer-Gallatin Forest Planning Process is a good example. Thirty years ago, that plan would have focused on resource extraction like timber sales and mineral exploration. Today, it’s much more oriented to recreational-resource management. You can make a big difference on what these plans contain and, equally important, how they are implemented.

6. If You Can’t Protect It, Don’t Promote It. With over four million visitors annually descending on Yellowstone, why on Earth are state and local tourism entities still promoting the heck out of it? Same goes for many of our local natural wonders which are already under siege from hordes of visitors. Maybe those marketing dollars could go into resource protection instead of resource promotion? Miracles do happen!

7. Go Non-Lethal. Here in bear country, its not unusual to run into hikers packing heat. No doubt about it, we have some pretty formidable critters out there—bears, lions, mama moose, and others. Thankfully, bear spray and appropriate behavior are replacing hot lead as the preferred way to handle dangerous wildlife interactions—safer for both people and wildlife.

8. Slow Down. What’s the rush? Why do we have to ride or run fast in beautiful natural settings? That’s like sprinting through a museum. I understand the thrill of speed and I was, for decades, an avid runner. But there are plenty of places much more appropriate to be moving at top speed—on foot or bike—than, say, prime grizzly habitat. Don’t rob yourself of the opportunity of becoming more intimate with the natural world.

9. Practice Self-Restraint. There are some places that should just be off-limits to recreational use, or at least some types of use. Call that discrimination if you want. But we accept access restrictions to places like hospital maternity wards, food-processing facilities, and airline loading gates. How about places where wildlife have their offspring, find critical nourishment, or use critical corridors? At least during certain times of the year (see Know Thy Ecosystem above) we should happily accept these restrictions.

10. Keep Those Secret Places Secret. You finally found a sweet outdoor haunt that seemingly hasn’t been overrun. DON’T post photos of it on social media! That makes about as much sense as sharing your credit card number with a stranger. No doubt others will eventually discover it. But without you putting a spotlight on this hidden gem, that process will take time, and maybe visitor impacts will be more gradual and managed. Don’t let your favorite fishing hole, campsite, or hiking trail go viral overnight. —Dennis Glick

Balancing Protection & Recreation on Missoula's Public Lands

Many believe that when it comes to outdoor-recreation opportunities, Bozeman kicks Missoula’s butt. That may be true, but when it comes to protecting the natural values that sustain our outdoor pursuits, Missoula could teach us a thing or two.

The Garden City boasts over 500 acres of city parkland, along with 4,200 acres of protected open space called “Conservation Lands.” Considering that conservation lands are accessed through 59 miles of trails, you’d think that recreation would be the tail wagging the open-space dog. Not so. As spelled out in their 2019 “Missoula Urban Area Open Space Plan,” protecting natural resources, including high-quality wildlife habitat and wildlife-movement corridors, is a primary goal. And city staff and community members go to great lengths to make that happen. Indeed, there has been a legacy of robust public involvement in crafting these plans.

Before newly acquired lands are developed for recreation, they are intensely studied by a team of well-trained City of Missoula conservation staff to identify things like the presence of unique species and habitats, and important natural features like wetlands and riparian areas. Their suitability for different recreational uses is also assessed. And sometimes they are determined to be just too sensitive for almost any human use—their value for wildlife and ecosystem services trumping the potential for recreational development. And as these areas are opened to the public, they are closely monitored to insure that resource-management goals are achieved.

This interconnected system of parks and open space features lots of interpretive signs. If a use is prohibited, such as a seasonal trail-closure to protect wintering ungulates, or qualified such as requiring dogs on leash to allow bird species to nest in peace, chances are there will be an explanation of why this action was taken.

Of course there’s been pushback by some recreationists, but less so all the time. Missoulians are justifiably proud of the ecological approach they have taken to managing their public lands. They consistently pass new open-space bonds despite the fact that many of these properties will never become outdoor gymnasiums for humans. You have to admit, it’s pretty cool being able to say that your city provides safe harbor for a resident herd of wild elk! —Dennis Glick

Joining the Movement

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks recently joined the Recreate Responsibly Coalition. This group of businesses, agencies, nonprofits, and influential voices formed in the fall of 2020 seeking to promote a set of safety and conservation ethics for getting outside amidst the pandemic. With more people recreating outside than ever before, it’s important that we protect our environment, ourselves, and each other. The coalition provides simple guidelines to help outdoor enthusiasts do what they love safely and responsibly.

Know Before You Go

Check the status and popularity of where you want to go. If it’s closed or overcrowded, make a new plan.

Practice Physical Distancing

Recreate with smaller groups of people and distance yourselves from other groups. Keep everyone healthy, and maintain the quietude we appreciate about the outdoors.

Plan Ahead

Know where you’re going, and bring what you need. Consider that businesses and facilities may be closed, so you might need extra supplies.

Play It Safe

Be considerate of others by choosing lower-risk activities to reduce likelihood of injury, and thus demand for health-care resources.

Explore Locally

Limit travel, recreate locally, and be considerate of your own impact on communities that you travel to.

Leave No Trace

Follow leave-no-trace ethics. Respect the land, as well as Native and local communities. Pack out all your trash.

Build an Inclusive Outdoors

Strive to improve accessibility in the outdoors for everyone by offering mentorship in your areas of expertise, donating used equipment, and volunteering for local organizations. —Kathleen Smith