Down in the Ditches

An Ennis local takes fish-rescues into his own hands.

Have you ever driven through Ennis in October and noticed a truck with an aerated five-gallon bucket in the bed? If so, you’ve crossed paths with Dave McCrory, also known as “Montana Dave,” on his way to or from the Madison River.

On average, Dave rescues roughly 1,000 fish each fall from five major irrigation ditches in Madison Valley. With his net, Dave scoops up between two and 50 fish every 30 minutes, which he then loads into his bucket and returns to the river.

Dave’s called Ennis home 27 years, but the issue of dewatered irrigation ditches in Montana has been ongoing for over a century. He’s not the first local to take matters into his own hands, and he hopes he won’t be the last.

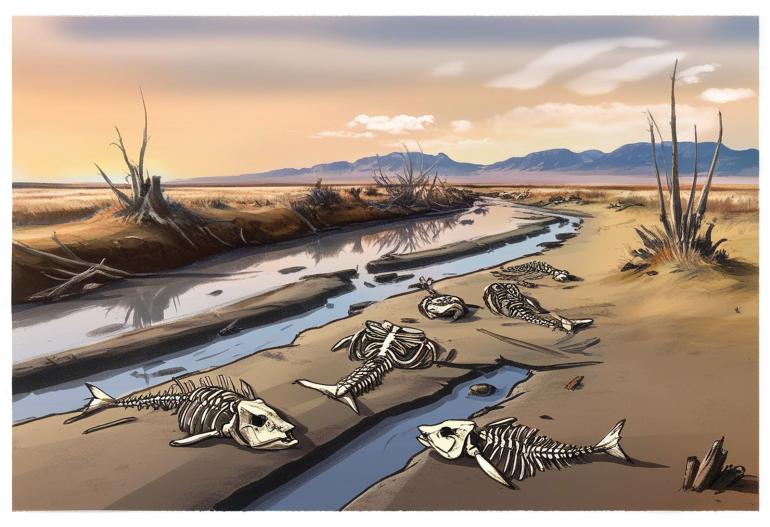

Stranded in ever-shrinking pools, the fish become prey to coyotes, bears, and birds.

Once the fall frosts set in and crops no longer require irrigation, the ditches dry up; often before the thousands of fish who have been living in these channels can return to the river. Stranded in ever-shrinking pools, they become prey to coyotes, bears, and birds. Fish that evade predation almost invariably die when the puddles of water freeze solid in winter. “It’s not a natural kill-off; it’s a man-made die-off.” Dave explains.

A simple solution could involve lowering the headgates gradually, providing the fish an extra few days to escape. For irrigators, however, there are bigger things to worry about than how or when the gates get lowered; including Montana’s unpredictable weather.

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks and other organizations are aware of the issue, but to Dave, their responses sound political and disingenuous. Some claim that the thousands of fish lost each season have little to no impact on the overall populations.

Dave calls bullshit. “These fish are the future of the river,” he says. Every fish saved means another fish able to reproduce and thus improve the overall population.

The fish Dave rescues range from fingerling rainbows to 23-inch browns. Over the years, he’s done this work largely on his own. There used to be local volunteers—schools would send kids out early to help, and others would donate a few hours to rescue fish. But that support has dwindled recently.

Neighboring states with similar issues have found solutions that could benefit not only Ennis, but irrigation ditches across the state as well.

What frustrates Dave most is the lack of involvement from local fly shops and outfitters. “The fish are their bread and butter, but no one wants to help, even though it would strengthen the backbone of their economy,” he says.

To add to the frustration, he recently learned that neighboring states with similar issues have found solutions that could benefit not only Ennis, but irrigation ditches across the state as well. Some states, like Idaho, have implemented fish-proof headgates that funnel fish back to the rivers. But they are expensive to build, and even more expensive to maintain in the long run. Another solution, currently undergoing trial runs, is using soundwave technology at headgates to deter fish from the canals.

But regardless of the solution, grants and funding will be needed to implement anything. Dave has written emails, researched grants, and shared the issue with anyone who will listen in hopes of attracting government attention. But until his efforts stick, local volunteers and a stronger community effort may make the biggest difference.

“These are our future fish,” concludes Dave. “Ennis wouldn’t be what it is without the fish. Our community should pay it back to them.”