Call of the Wild

Dick Vincent's lasting impact on wild trout populations.

Montana’s meandering, scenic rivers are known around the globe for their access to wild trout. Fly-fishers come from far and wide to chase browns, rainbows, and even the elusive cutthroat, all of which are born, and grow to adulthood, in this natural environment.

However, stabilizing these populations hasn’t always been easy. Wild trout face water-level manipulations, displacement by non-wild fish, and outbreaks of parasites—but thanks to one man’s unwavering dedication to the wellbeing of wild fish, Montana’s fisheries are what they are today: strong, healthy, natural, and wild.

Early Years

Born in Bozeman in June of 1940, Richard “Dick” Vincent grew up in the tiny Montana towns of Norris and Garrison. He fished the waters of the Madison and Clark Fork rivers alongside his father and grandfather. Raised in a family of ranchers, Dick’s affinity for the outdoors was complemented by a growing interest in biology. “I grew up on it and it was the love of my life, it was the best river on the planet,” says Dick, recounting his early years on the Madison.

Throughout his high-school years in the late 1950s, Dick worked on a few small water-chemistry projects, alongside biology teacher Bud Lilly. Dick attended Montana State College (now Montana State University) to pursue a biology degree in the fall of 1959. Prior to starting school, Dick had never been east of Livingston, but he later spent his summers surveying fish ponds, counting fish via electrofishing, and tagging fish all across Montana. Dick completed his master’s degree in 1966, during which time he worked in Yellowstone Park on an annual aquatic-insect study, with many of the trips into the Park being on snowshoes.

In the Field

While searching for a place to rent near campus, Dick met Region 3 Fisheries Manager Bud Gaffney and was subsequently offered a job. This marked the beginning of his career in fisheries, where he played a pioneering role in developing electrofishing techniques for large rivers. Dick worked with his uncle to adjust shock intensity to better protect the fish. He also developed a population-tracking process by dividing data into size and age—all of these studies being done sans calculators or computers.

In the late 1960s, Dick brought his research to Montana Power Company (who controlled the streamflow of the Madison) to share habitat data on the welfare of wild trout. Montana Power Company would de-water the Madison prior to runoff, taking about half the water out of the river, which adversely affected the recruitment of brown trout. Dick made a flow pattern based on data collection from water reduction and snow surveys, and the power company agreed to follow the new plan. The following year, brown-trout recruitment and population spiked in the Norris area.

“When we quit stocking the Madison, populations of wild trout, both rainbow and brown, just started to explode,” –Dick Vincent

However, other sections did not fare as well. Due to thermal problems, the Norris section was a much more challenging habitat, so it was a mystery as to why the fish did well there but struggled in the upper section of Varney. Alongside his fellow biologists, Dick realized one major difference among the two sections: Varney was heavily stocked, while Norris was not stocked at all.

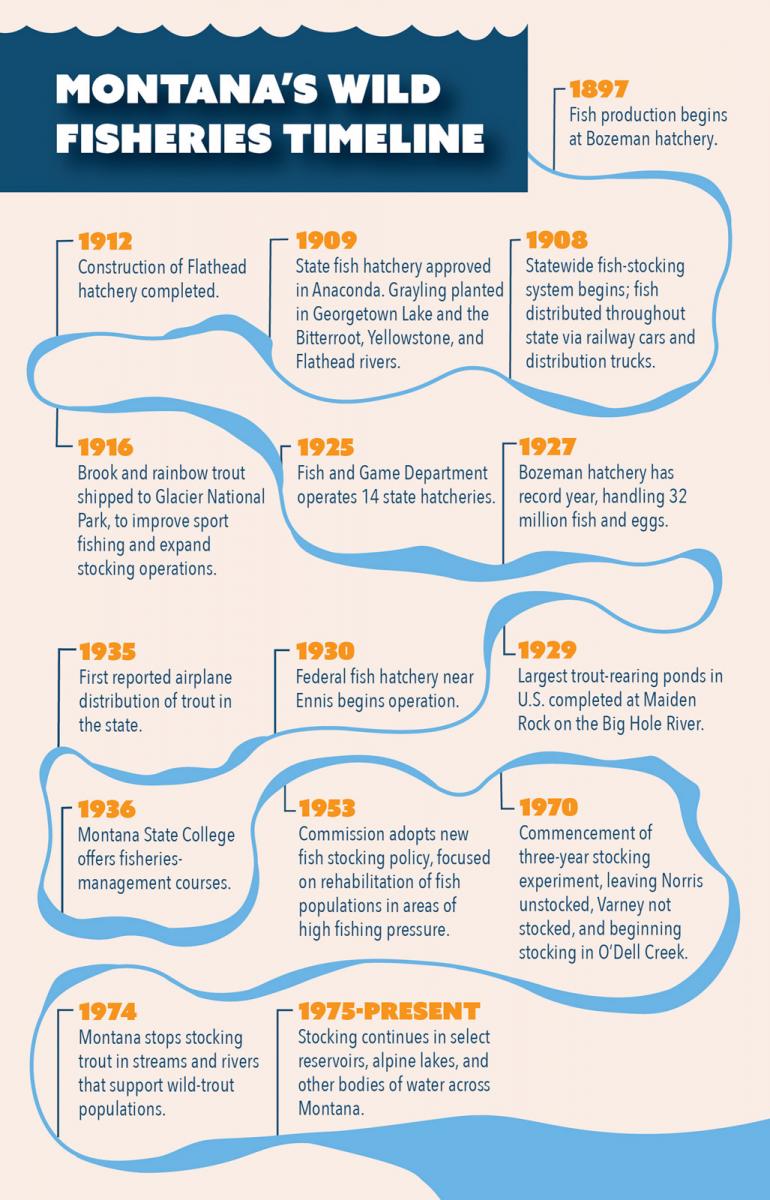

In 1970, Dick and his team began a three-year study, leaving Norris as-is (unstocked), Varney not stocked (formerly stocked), and O’Dell Creek stocked (a formerly unstocked spring creek whose population “never varied.”)

Risks & Rewards

Stocking wild rivers had been done by Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) since the early 1900s (then called the Fish and Game Department). There was a universal belief across the fishing community that the more fish that were stocked in the river, the more there were to catch—so the rivers were stocked heavily. The fishing economy relied (or so they thought) on stocking the rivers. Due to its proposal to end stocking, the research plan created an uproar among sportsmen, tackle shops, and lodge & restaurant owners, as they believed this would kill their businesses.

Dick faced a lot of backlash, and it translated into his life beyond work. When asked about the controversy among the community, Dick remembers, “Meetings were almost to the point of violence at times, and certainly there was verbal abuse.” He was asked to leave bars, the team’s equipment was damaged on the streets, and he was pestered and yelled at in public; but nonetheless, he continued his pursuit of answers.

Dick’s reputation wasn’t the only thing on the line during his studies. He divorced during the study, after being married three years, due to working long hours and being gone all the time. In 1973, he met a gal named Twyla and they married in the fall of 1974, with Dick adopting her three sons.

Dick’s work wasn’t rooted in making money or holding power, but in truly understanding the biology of wild trout and laying the groundwork to help them thrive for years to come.

Fish management was misunderstood among the masses, and the opposition to Dick’s study continued to grow even among Dick’s own department and commissioners.

However, the results turned heads. “When we quit stocking the Madison, populations of wild trout, both rainbow and brown, just started to explode,” says Dick. Rainbow numbers doubled in the first year in the non-stocked section of Varney. By the third year of the study, rainbows had increased by 1,000 percent and the number of browns doubled. When looking at the effects on O’Dell Creek populations, however, he found that wild-trout numbers were cut in half.

“Dick was obviously technically solid, but that wasn’t the most important thing about his approach,” says Ron Spoon, a fellow fisheries biologist who worked alongside Dick in the 1990s. “Nor was he an outgoing marketing type that had big ideas without much to back it up. I believe his magic and effectiveness came from his bigger-picture instincts with rivers and fish. In his gut, he knew how the system worked and what was generally needed.”

Gone Wild

In 1974, the final research results went to the Montana Fish and Game Commission, and stocking in wild-trout streams became prohibited across the state. Dick soon had data from not only the Madison, but also from trout numbers doubling in the Gallatin. Montana was the first state to implement such a program, and word spread across the nation.

Hatcheries didn’t come to an end, however. Many waterbodies, including reservoirs and alpine lakes, continued to be stocked, and are still stocked today. What changed was that our formerly-wild coldwater rivers became wild once again.

Through the remaining years of his career, Dick helped establish catch-and-release practices and modified fishing regulations to prevent overfishing. He became Fisheries Manager of Region 3 in 1988 and later Whirling Disease Coordinator during the outbreak in the 1990s.

After 42 years with FWP, Dick retired in 2008—about the same time the trout populations recovered substantially from whirling disease. Dick’s work wasn’t rooted in making money or holding power, but in truly understanding the biology of wild trout and laying the groundwork to help them thrive for years to come. “Dick was an honest and humble steward who wasn’t trying to do something flashy,” says Spoon. “He was just trying to do his job.”

Let Montana’s glistening rivers and wild-fish populations remind us that nature’s own design offers an experience far more spectacular than the chase of any artificially-bred counterpart. Cheers to the honest, meaningful work of Dick Vincent, and to the 50th anniversary of keeping Montana’s rivers wild.