Burn Notice

The bygone guardians of Yellowstone.

I awoke in the middle of the night to brilliant flashes of light. At first, I thought someone was shining a light in my face before I fully awakened and realized to my horror that a huge thunderstorm was headed right for me. I was in Yellowstone’s Divide Lookout, and though I had led interpretive ranger day-hikes to the tower, I had never spent the night in it. I pulled out the Lookout Manual and turned to the “What to do in case of a thunderstorm” page. I groaned when I read the first sentence: “Be sure that all lightning rods are securely attached.” The dark, ominous cloud passed directly over me with lightning strikes all around, but thankfully no direct hits. Behind the storm clouds, a full moon emerged and I witnessed a complete moonbow over Shoshone Lake below. Experiences such as these have long made the job of a Fire Lookout uniquely magical.

I first began working in Yellowstone in 1968, and up through the 1987 season there were very few fires in the Park due to the heavy snowpack and wet summers. That changed in 1988 with the huge fires that burned over a third of the Park’s acreage. In the years since, climate change has resulted in shorter and warmer winters, and drier and longer summers that have produced a landscape much more prone to combustion.

Over the years I have visited each of the Park’s lookouts. Positions at Mount Holmes and Mount Sheridan were truly remote-duty assignments.

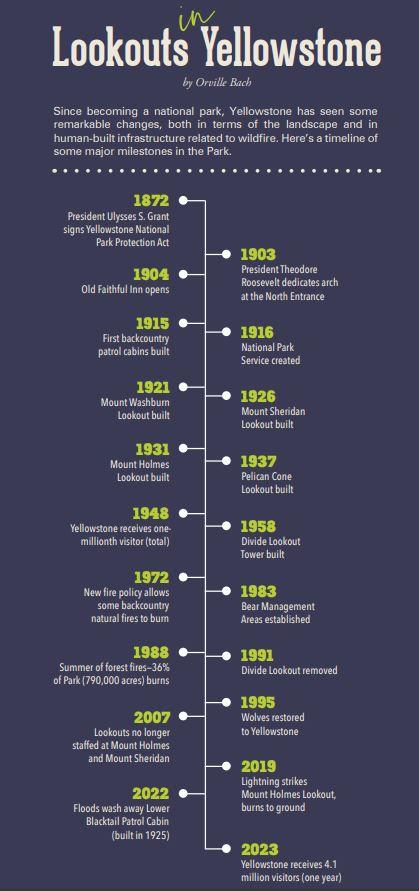

Still, though, Yellowstone has a “natural burn” policy, where most lightning-caused fires are allowed to burn if developed areas are not threatened—but early fire detection has always been critical. Fire lookouts have historically been an essential part of detection efforts, in Yellowstone and beyond. At one point, there were thousands of fire lookouts across the West, including several in Yellowstone. Originally, 16 were proposed in the Park, but 12 were actually constructed. The three primary lookouts were Mount Washburn, built in 1921; Mount Sheridan, built in 1926; and Mount Holmes, built in 1931. Secondary lookouts included Divide, Pelican Cone, Observation Peak, Purple Mountain, and Bunsen Peak.

For most of the last half-century, the primary three were staffed for the summer season, but that ended in 2008 when the National Park Service began staffing only Washburn. Developments in fire-detection technologies with satellites and flyovers made many lookouts obsolete. Still, Washburn continues to be staffed primarily because of its central location and the fact that the summit represents one of the most popular destination hikes in the park.

Over the years I have visited each of the Park’s lookouts. Positions at Mount Holmes and Mount Sheridan were truly remote-duty assignments. Each required a roundtrip hike of over 20 miles. In 1974, I hiked up the backside of Holmes and inadvertently surprised the watchman. When I knocked on the door he about jumped out of his jeans, since he had not seen me approaching on the trail. Visitors were rare to begin with, but he had never seen anyone hike up the back side of the mountain.

During that same summer, an embarrassing incident occurred involving the same surprised watchman. I was stationed at Norris Geyser Basin where we had a splendid view of the summit. In those days, we only had two channels on the Park radio, and one of them transmitted Park-wide. On that particular day, the lookout on Holmes made a frantic call to fire dispatch that he needed the helicopter to return to the summit despite having delivered his weekly food rations earlier in the week. It took a while, but finally he confessed: he had ventured out to the pit toilet and a strong wind had blown the outhouse down on top of him and he couldn’t get out. Fortunately, he had carried his portable radio with him. The entire Park heard the conversation, and I could not help but chuckle from my vantage point at Norris gazing up at the summit. Tragically, years later, the Holmes lookout building was lost when lightning struck it on July 16, 2019, and it burned to the ground.

About 40 air-miles to the southeast from Mount Holmes is the Mount Sheridan Lookout, which I visited in September of 1975. A lookout by the name of Jim related to me just how few people ventured up to the top. After all, it was about eight miles just to reach the base, and then you had to climb almost 3,000 feet in another three miles to reach the summit. Years later, in 1994, I hiked up to the Washburn Lookout and I was surprised to also find Jim there. Amazingly, he remembered my visit in 1975—although it had been almost 20 years earlier. I asked him why he transferred, and he said it was because Sheridan was so isolated, and that he enjoyed talking to the many visitors who come up Washburn.

Some of the secondary lookout posts were also utilized for much of the latter half of the 20th century. For example, Pelican Cone was occupied during the summers from 1984 through 1989 by Kerry Gunther, who is now Yellowstone’s bear biologist. From his lofty perch, Kerry conducted research on grizzly behavior to confirm the effectiveness of the Park’s Bear Management Areas that were implemented in 1983. Kerry said that he once went 63 days without seeing another human. Pelican Cone still stands today and is occasionally used by rangers and biologists.

With a chuckle one evening, Ed warned me about the “ghosts” of Washburn over the phone. And indeed, in the subsequent weeks I heard strange noises that I could never explain.

During the late ’70s and early ’80s, the interpretive ranger staff at Old Faithful utilized Divide Lookout for fire-ecology hikes for the public. The lookout tower was constructed of sturdy angle iron, and the spiraling staircase led to a nice cabin 68 feet above the forested floor. Once above the forest canopy, fabulous views could be had in all directions, which included the Tetons, Yellowstone and Shoshone lakes, the Upper Geyser Basin, the Absaroka Range, and peaks to the north such as Holmes and Electric. In a very controversial move, the Park Service dismantled and removed this lookout in 1991.

With all other towers phasing out of commission, old-timer Ed Stark served as the Park’s sole remaining lookout at Mount Washburn for 17 years through the 2022 season, but was unable to return in the summer of 2023. That’s when I got the call to fill in as a volunteer for the latter part of the season. I had previously worked at about every location in the park, spending most of my seasons at Old Faithful. Living at Mount Washburn would be a truly magical experience.

Unlike the isolated duty posts at Holmes and Sheridan, working at Mount Washburn involves lots of visitor contact. However, it did not take long before I experienced one of the reasons why this post needs to be staffed. Despite warning signs at the trailheads below, some visitors hike up unprepared for the sudden changes in weather. One particular day was nice and sunny with a temperature in the high 70s. I was downstairs in our little glass-enclosed visitor center, chatting with visitors, when I noticed that several had started back down wearing only shorts and t-shirts with no daypacks. About 15 minutes later, a hailstorm passed over the mountain and the temperature plunged by 40 degrees. Fortunately, the group returned to the shelter of our inside viewing room. All were soaked and shivering. I went upstairs and got some towels and brought down some hot chocolate for the group. I then looked at the radar on my phone and realized that it would be an hour before the storms blew over. I kept my visitors until the storm passed and then sent them back down the mountain.

Ironically, though, being perched as a fire lookout at 10,243 feet also exposed me to the same lightning that I was supposed to be detecting. When thunderstorms passed directly overhead, I hoped and prayed that the lookout was properly grounded as lightning flashes and deafening claps of thunder occurred. The fierce winds were also a surprise to me. Throughout my stint on top of Washburn, I kept in regular contact with the old veteran Ed back in Massachusetts. One day Ed called me up on the phone (yes, there is excellent cell service at the lookout) and asked, “How did you enjoy the Washburn breeze last night?” Ed monitored the weather from his home and wanted to know how I was dealing with sustained winds of 60mph with gusts to 90mph. The lookout stood up well to the winds, but you have to be very careful climbing up and down the stairs, lest you get blown away (no pit toilet here!).

With a chuckle one evening, Ed also warned me about the “ghosts” of Washburn. Granted, I heard strange noises that I could never explain. Once night settles in and it’s pitch dark, the place becomes downright spooky at times. One evening I remember vividly, it was completely black outside and I was eating a late meal around 10pm, when suddenly there was a loud knock right at my window. Like the fellow I surprised at Mount Holmes, I just about jumped out of my jeans. I had forgotten to lock up the visitor center and there, standing at my window, was a guy with a beard and a plaid shirt. He had seen my light on and was curious. Late night visits were rare, but they did happen, especially on nights with a full moon.

After a season of being mesmerized by the magical and changing moods of Yellowstone as viewed from the top of Mount Washburn, I departed on September 29, just before a snowstorm hit. I don’t think there’s a bad job location in Yellowstone National Park, but it would be hard to top the Washburn post. Any visitor to the summit of Mount Washburn gains a wide view of much of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem that makes up over 18 million acres and extends well beyond the Park’s boundaries. From up high, one can truly realize just what a special land this is, and why it’s critical that we protect the entire ecosystem.

Orville “Butch” Bach worked 47 years as a seasonal interpretive National Park Service Ranger in Yellowstone, and currently volunteers in the backcountry and at the Mount Washburn Lookout. He resides with his wife Margaret in Bozeman.