Sting and a Miss

Learning about bee allergies the hard way.

I had occasion to think of Louis Leakey. Dr. Leakey and his wife, Mary, were the ones who discovered the fossil jawbone and teeth of an early hominid at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania in 1959. Actually, it was Mary who found it; Louis was laid up sick that day. As often is the case, Louis got the credit for what Mary accomplished. Anyway, the discovery led to evidence that it was Africa, not Asia, where humans first evolved, later to populate the earth. But it was Louis I thought of on that occasion, not Mary. And it wasn’t the thought of old bones, but of bees. More about that later.

It was early September and I’d had the rare good fortune of finding an isolated campsite along a stream about an hour from White Sulphur Springs. I was breaking camp after an ideal weekend of solo fishing, exploration, and savoring my own camp cooking—if you call cracking a tin of smoked oysters “cooking.” The fresh cool of the early morning had morphed into uncomfortably hot conditions by the time I’d finished loading the truck. It being Montana, I wasn’t sweating all that much, but was flushed with the heat.

I closed the lid on the topper over the pickup bed. A circling bee that wanted entry to the truck vented his frustration when I sealed the entrance. He stung me in the neck. Ouch, but no big deal. I grumbled at the minor annoyance that marred the end of an enjoyable weekend.

Behind the wheel, I started driving the double-track back toward civilization. The only other camper in the area had departed an hour before. After one, maybe two minutes, I started itching. Soon the itching gained momentum and couldn’t be ignored. Hives? I wondered. I lifted my t-shirt and examined my midriff. I discovered a lumpy sea of bumps populating my six-pack. I thought of my first-aid kit, equipped to stop the flow of blood, defend against pain with ibuprofen, or dose myself to combat dysentery, but alas, no Benadryl.

So, I continued to drive. After all, I had no breathing problems or anything else I interpreted as threatening. But the itching intensified, and I stopped to take inventory of my hive crop again. Now I had hives everywhere, including the palms of my hands and soles of my feet. Impressive.

Back to Dr. Leakey. I had the sudden recall that Leakey, despite his scientific achievements and international fame, had perished on the plains of Africa from a bee sting. His illustrious career ended by an insect. Like one more itchy hive, the prospect of my own perishing popped into consciousness. I began to worry. (I later learned that Leakey didn’t die of his bee sting. It turns out he got into a swarm of bees and was stung hundreds of times. In his thrashing about he got badly banged up and it was said that his health and psyche were permanently affected.)

Still, no tightening of the throat, no wheezing, just the big itch. I drove to White Sulphur Springs, squirming and worried, and stopped at the pharmacy. I’m a physician. I decided I didn’t want to take Benadryl, because I didn’t want to be drowsy for the drive home. So I prescribed myself a healthy dose of Prednisone and asked the pharmacist if she minded me hanging out for a while. Not feeling 100 percent, but breathing fine, I found a chair and took a seat, waiting for the steroid to take effect.

I recall telling the pharmacist that I was maybe a little woozy. The next thing I knew, I was bouncing over the curbs on Main Street, supine on a gurney, being wheeled to the nearby hospital ER. A platoon of Florence Nightingales had converged on the drugstore, loaded me up, and whisked me away, like a scene from an old war movie. By good fortune, a doctor was present. In an explosion of professionalism and competence, the team had me plugged into oxygen, IV, and beeping monitors. I received it all: epinephrine, antihistamines, more cortisone, and focused attention. I spent the night there.

As any Montana guy who’s had an outdoor (mis)adventure can attest, the most difficult part of such an ordeal is the call to one’s wife. The “Don’t worry, Honey, but...” phone call. The word “hospital” does not go over well. By the time I talked to her, it was assured that I was going to be fine and homeward bound the next day. My wife was happily pleased that I was okay; I was buoyed up by her loving concern. I knew, however, it was likely she viewed this episode as additional evidence that I was not always very wise. Guilty as charged.

Next stop: the allergy doctor. After hearing my story, he related that “immunotherapy,” what we’d all call “allergy shots,” should prevent further serious reactions. So began my relationship with nurses and needles. I did the drill, taking shots weekly to start, then eventually tapering. I never ventured into the wilderness without my EpiPens.

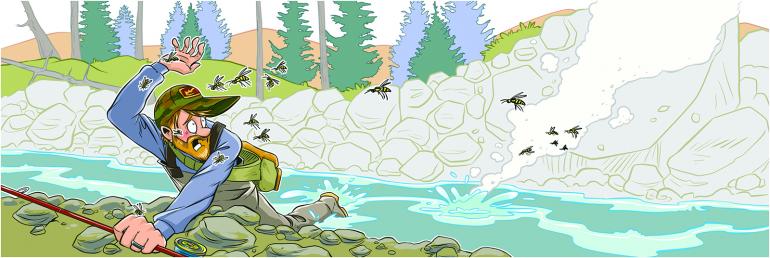

So, guess what? Almost two years to the day, I’m off fishing by myself on a small stream on an exquisite early-fall evening. Windless, low-angle light with the beginning of an evening glow, a responsive fish at almost every hole. Perfect. Moving upstream, a steep, five-foot bank required a butt-slide to reach the water’s edge. As my bum met the ground, Dr. Leakey’s swarm of yellowjackets erupted from their earthen home. They found any exposed skin, even taking the effort to fly up the sleeves of my t-shirt. Like Leakey, I flailed, whirled, stomped, and ran. When I made it across the river, the bees had given up, but I knew I’d received multiple stings. I ditched my vest, unzipped the compartment with my epinephrine pens, got them ready, and waited for the onset of symptoms, or even my demise.

Nothing happened. Nothing. In my emergency kit was some Benadryl; I wasn’t sure it was necessary, but I took some. I made my way back to our family cabin and took inventory. I had six stings, and at least two stingers were still attached, one on the back of an ear, one on the back of my neck. I showed up at the neighbor’s house, asking for help removing the stingers. I didn’t think I could get them out without injecting more venom. They had a son with a bee allergy, so these other Montana Nightingales assessed my situation calmly and commenced to help. The mama of the house efficiently flicked out the stingers with a credit card. I lived.

I talked to the allergist the next day. He said that although he acknowledges it’s sometimes difficult to assess the effectiveness of allergy shots, the immunotherapy for bee stings is very good. With wasps and bees, he said, “our profession has hit a home run.” I could attest to that.

I now remain armed with epi, show my fishing buddies where my bee-sting kit is, and try not to do anything dumb around bees. I remember once, years ago, I was at a rancher friend’s house. He raised honeybees. One of the little fellows landed on the back of my hand, and I remember telling my son, “I think this one’s a drone; they don’t sting.” I started to brush the bee aside. The little worker must have been insulted that I called him a drone—he arched his back and stung me. Dang. So much for my drone theory and a cavalier attitude. From now on, when confronted with a menacing bee, I consider the critter to be like a teeny tiny grizzly bear. I won’t be cavalier. I’ll just back away slowly.