Free Montana

Q&A with educator Thomas Elpel.

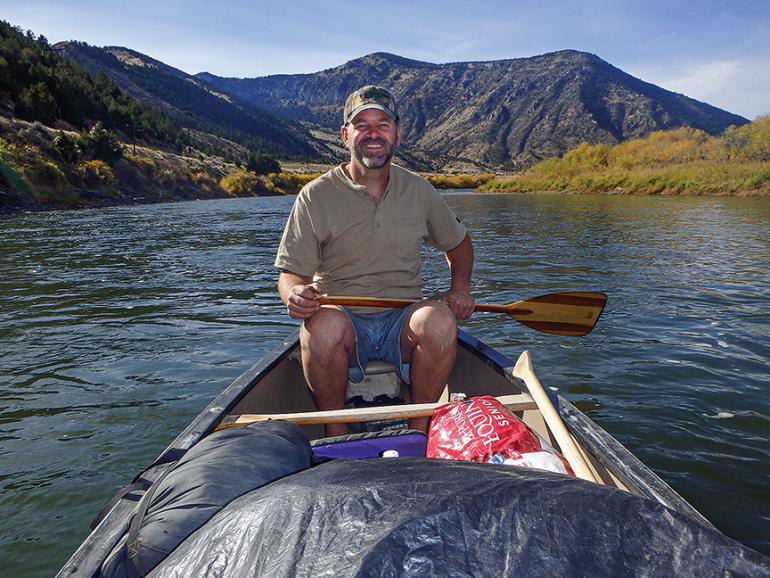

Thomas Elpel is an author, educator, and builder out of Pony, specializing in survival skills and primitive living; he’s also an outspoken proponent of public access. I recently sat down with him to talk about his work, his project the Jefferson River Canoe Trail, and the idea of “Freedom to Roam.”

Nicole Qualtieri: Tell us about the work you’re doing.

Thomas Elpel: I teach through living experiences, not lecturing, and my program tends to be more immersive. It started as Hollowtop Outdoor Primitive School, but now the adult program is Green University and the kids program is the Outdoor Wilderness Living School, or OWLS.

OWLS is about getting kids excited about nature. We do overnight camping trips that last four days and three nights and we try to make it so it’s not a structured class; it’s more of a flow. The kids make their own fire kits, and then they use that fire to cook their food. They find their own dishes naturally, we do some foraging, and they get greens and mushrooms. We make a stir fry in a slab of bark using hot rocks.

With our adult program, it’s more of that immersive experience, and I like the deeper conversations that we have with people who are here for a long time; our program is structured toward the long-term. You have to meet people where they’re at.

NQ: Speaking of boundaries, where did the Freedom to Roam idea come from?

TE: I grew up in a time in Montana before no-trespassing signs; I could walk anywhere I wanted, so I had no concept of places I couldn’t go. After high school, I walked 500 miles across Montana, and that individual discovery was important.

Over the years, people from a different culture moved to Montana, put up no-trespassing signs, and chipped the land. Not only are landowners keeping people out, but they’re losing access to land themselves by encouraging fences and signs.

Even people who grow up here in Montana get lost in the electronic world, and they’re not connecting with the natural. As the no-trespassing signs have gone up, it’s become more necessary to ensure we can still have access for the public. Stewardship does go hand-in-hand with having the freedom to roam, out of respect for land and landowners.

NQ: What is the Jefferson River Canoe Trail? How did it come about?

TE: The canoe trail was born out of this idea of Freedom to Roam. I walked much of this area before I floated it, and now I want to shift the perception of the Jeff—it’s like having a long skinny national park in our back yard.

I wanted to build a destination, rather than a corral to hold people in. The canoe trail is connecting isolated parcels together by water, and I wanted to think about what I could do in the long run and how I might build a water trail that is more on the scale of the Appalachian Trail that has designated campsites for folks all along the way. Really, it just comes down to creating a map and language around this place. If you call something a national park, it begins to look different to the public. So with the canoe trail, we applied names to some patches of BLM and state land, and we bought one campsite. Most of it is done by acknowledging what’s there and providing maps and language.

NQ: What should we as Montanans take away from this?

TE: The one thing that’s been consistent all along here has been the wilderness aspect and how this applies to living in the modern world. One of the interesting things I notice with my internship program is that when interns come from a place with boundaries, they act as if they’re in a cage. They complain about the cage, yet they’re so conditioned to be in the cage. Out here, we have all these thousands of acres to explore. We can’t take that for granted.

To learn more about Elpel’s work, visit hollowtop.com.