Cabin Down Below

The trials and tribulations of building an illicit slopeside ski shack.

Let me set the scene. We were four high-school ski buddies spread across the state for college, but from Thanksgiving to mid-April, we would meet for skiing on weekends. Our most common destination was a small ski hill, about equidistant for everyone, but a short drive for no one. Commutes ranged from two to four hours—with good roads. It was a serious time-suck in need of remedy. Plus, our “resort” had no slopeside lodging, and even the cheap hotels in the nearby town were not affordable on our student budgets. So, we put our heads together. Add in some testosterone, alcohol, and the THC-induced inspiration of having free ski-in, ski-out lodging for our mountain, and a dream was born. The search for a location commenced, and we broke ground the day after Christmas.

Site Selection

The site had to meet several key criteria—the most important being that we could ski to it from lift-served terrain, and then ski back to the mountain base. It was also essential that we could park somewhere nearby, without having a vehicle towed or plowed-in overnight. Finally, while meeting all these requirements, it still had to be hidden from view, both in winter and summer.

We located a small, bare area about 30 yards from the road, completely hidden by a dense stand of trees. From the plow-formed roadside berm, it was a downhill march that took anywhere from three to 15 minutes depending on conditions. Sometimes the sun crust could support your weight for the first 20 yards that followed the edge of a meadow, but there was always a struggle in the shaded final ten yards. Technically, you could ski to it, but we rarely did because the uphill trudge the next morning was excruciating without boot tracks to follow. On more than one occasion, though, we paid this penalty when it took 30 minutes of strenuous exertion just to wallow through unpacked snow back up to road—a brutal endeavor.

Construction

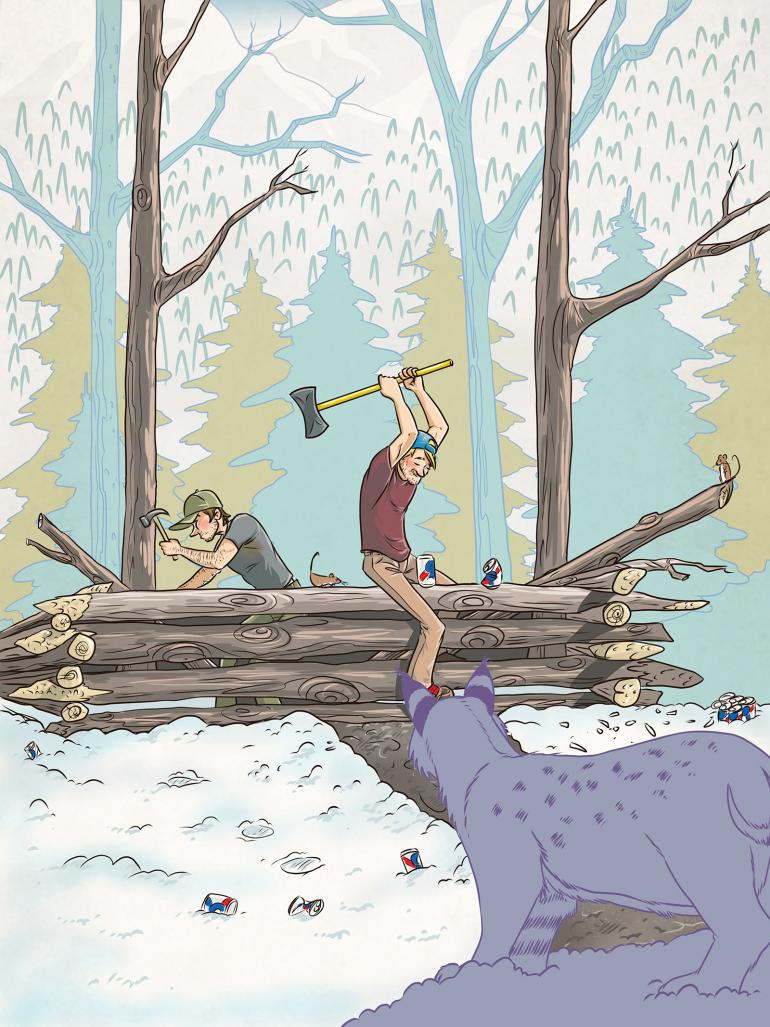

Despite all the downfalls, many of which were not uncovered until later, we thought our site was perfect. In the interest of minimizing attention from the road, all work was done with manual tools: axes, handsaws, pickaxes, shovels, pry-bars, hammers, and nails. On the first day, we shoveled out the snow, did our best to level the frozen ground, and dragged nearby deadfall to the site. We settled on a plan to use the standing trees surrounding the site to support the cabin walls, which explains why the shape was an irregular hexagon, vaguely resembling an extremely wide coffin with a total area of about 180 square feet.

After much debate, we choose the name “Woody’s.” It captured the materials of manufacture, was easy to remember, and didn’t identify it as a cabin.

We deferred to the Lincoln-log style of notching and stacking logs to build walls about five feet tall. Though we cut deep notches, the irregular fit of natural logs left significant gaps between each layer. Chinking was not available in our supply chain, and would have required a significant investment; so, we settled on filling the gaps by stapling a strip of tarpaper to the outside of each gap and stuffing it full of insulation from the inside, then covering it with more tarpaper.

Even with the complex shape, we managed to make a simple roofline with a single peak bisecting the length of the coffin. At its peak, the inside was about seven feet tall at one end, and six feet tall at the other. An old wood-burning stove with a built-in cooktop was situated on bricks mosaiced into an oddly-shaped nook. The short wall at the head of the coffin was a four-foot space between two immense trees. This space eventually became the door, where we wedged a piece of one-inch plywood cut to the contours of the trees to exactly fit the gap. A couple of eyebolts, a chain, and the pry-bar became the locking mechanism between visits.

It took six grueling days to get to this stage, but we’d excavated, framed, and roofed our cabin to provide a reliably dry nook in the woods. On New Year’s Eve, we passed out at 9pm from exhaustion.

We awoke the next morning, however, and realized that the cabin still needed a code name. We didn’t want people to know that we had a cabin in such a prime location for fear that it would be discovered and torn down, or even worse, over-occupied. We were concerned that word would get out to other ski buddies, and next thing we knew, the cabin would be full of people we didn’t know. We didn’t realize how few people were willing to sleep in a glorified snow-cave in the middle of the woods in the peak of winter. A few college acquaintances would accept an invitation for a weekend, but very few would come back a second time.

Still, it needed a code name. After much debate, we choose the name “Woody’s.” It captured the materials of manufacture, was easy to remember, and didn’t identify it as a cabin. A pre-weekend email, we figured, might be something like, “Hey guys, I’m heading to ski Saturday morning and staying at Woody’s that night with one friend. I’m bringing plenty of dinner and PBR if you want to join us.” And thus, the cabin received its official moniker.

Improvements

Shortly after the new year, two of us decided to spend the first pre-ski night in Woody’s: dreaming of sleeping in until 8, eating a quick but hot breakfast, and lining up for first chair by 8:45. We hauled a full-sized mattress into the cabin to protect from the cold ground, and chopped plenty of firewood to heat the place. We brought our warmest sleeping bags, a lantern, some quick and easy foods to prepare, and beverages to consume while the snow accumulated outside. Installing a storage cabinet consumed our attention until 1am, and we went to sleep with large flakes filling in our footprints every trip out to the “outhouse tree.”

The floor installation was an all-nighter, requiring the hand-hacking of roots, prying of rocks, and profiling one side of every 2x4-inch “joist” to match the contours below.

Even with the stove and heavy sleeping bags, that was a cold night. The earthen floor and gaps in the walls were just too much. We did manage to get to sleep, but the inside of the cabin was pitch black, and without a clock, we didn’t get out of bed until sometime after 10. So much for first tracks. Once we realized our error, we scrambled to heat water for coffee, slap together breakfast, and slog back up to the road. When we finally did make it to the lift, it was around 11:30, and we skied the rest of the day without a break to make up for our late start.

That night, back at the cabin, we decided we needed to install skylights to trigger us to wake up, a floor to insulate us from the ground, and bunks to raise us toward the warmest part of the cabin. All of these were installed in succession over the next several months. The floor installation was an all-nighter, requiring the hand-hacking of roots, prying of rocks, and profiling one side of every 2x4-inch “joist” to match the contours below. We stuffed the gaps between studs with insulation, and fitted a plywood mosaic to the awkward corners, nooks, and crannies. A final application of carpet provided a much-needed soft touch.

By now, we had remembered to bring an alarm clock to prevent missing morning powder, and the skylights—another labor-intensive job—were bringing much needed daylight into the cabin. Regular roof-shoveling became required to get the full effect of the skylights, and by peak snowpack, the cabin was less of a cabin and more of a snow-cave with tree-lined walls. We had to dig a trench downward to the entrance, and the heat from the cabin melted the surrounding snow, forming a solid sheath that helped protect from wind and provided another layer of insulation. Overall, it was starting to become a real cozy place.

Season Two

The start of the following season was exciting. We’d made a few more improvements to Woody’s over the summer: shelving, more storage, cooking supplies and utensils, and a dishpan sink. We padded the bunks and cleared the pathway of major deadfall and obstacles that made the trip last winter such a hassle. We thought we’d use it every weekend and then some, logging maybe 40 nights and 80-plus days of skiing that year. That year also saw the release of Tom Petty’s album Wildflowers, with the song “Cabin Down Below.” Tom Petty wrote us a theme song!

The butter turd was exactly that, the fecal material of an animal, containing a stick or two of butter combined with fur and rodent remains.

One early-season weekend, we left a few extra supplies at Woody’s, including ramen, butter, peanut butter, bread, and some mousetraps to ensure we didn’t have to hear ramen packets being torn open in the middle of the night. The traps were the glue-type that catch their targets and keep them in place until you dispose of them. When we returned the following weekend, we found that the traps had indeed worked, but they were displaced from one end of the cabin to the other, and only 12 tiny feet were left in the glue. That’s also where we found “the butter turd” which gave us some clues about the animal that had come in and helped itself to the trapped prey. The butter turd was exactly that, the fecal material of an animal, containing a stick or two of butter combined with fur and rodent remains. The size and shape made us think that it was a cat, and we found a gap between one of the walls and the floor that easily would allow a bobcat to enter. Further investigation led us to round paw prints that confirmed it was indeed most likely a cat. Clearly, we had more work to do before making Woody’s our weekend home.

With the animal-proofing complete, Woody’s was soon hosting people nearly every weekend, and sometimes as many as six of us would crash on a given night. The bunks were widened to accommodate two in a tight fit, and two would share the full-size mattress on the carpeted floor. Still, with six occupants in 180 square feet, it required a choreographed effort to make dinner, retrieve beers from the “floor cooler,” or even to let someone outside to repatriate that beer to the forest floor. Close friendships got closer, and the bonds of skiing incredible days together were made even deeper by spending those nights so intimately with those same friends.

The Later Years

Use of Woody’s peaked in years two and three, but the following couple years still saw plenty of visitation. We did a good job of keeping a lid on its existence and location, and we set a ground rule that anyone other than the original four builders had to be accompanied by one of us to stay there. Our fear that the cabin would be overrun by others never materialized. But as we graduated from college and moved to other states, Woody’s saw less and less usage.

Sadly, we lost one of the four builders a couple years ago. Colin’s lust for life and adventure was contagious.

Now, it’s been 20 years since I last saw Woody’s, not daring to stop even though I’ve driven past it several times, for fear of finding the walls fallen, and the contents strewn throughout the forest. Or perhaps a hibernating bear or maybe a descendant of that bobcat making a den out of the partially standing structure.

Sadly, we lost one of the four builders a couple years ago. Colin’s lust for life and adventure was contagious, and more than one of the eulogizers talked about how Colin encouraged them to do firsts: first cliff jump, first raft trip, first concussion, first hypothermia, first car accident, first construction project, first moonlight ski tour, first streaking the lift line on closing day.

After the funeral, I heard that the trees that hold Woody’s door in place have grown to a point that the door must be cut away for somebody to get inside, but the walls were standing, and the roof appeared intact. Next time I drive by, I’ll make the trek down to Woody’s with a hatchet, hacksaw, and bear spray in hand to see for myself how our old haunt is doing. No matter what I find, I’m looking forward to wandering the site, remembering those weeks we spent building, and the years we enjoyed our Cabin Down Below.