Chasing John Colter

Turning 30 wasn’t difficult for me, but I had reservations about 33.

Fine lines have sprouted around my eyes, like the map of a well-developed city. My yoga teacher pokes my belly when I’m in warrior pose and says, “What’s that?” I never get the look from guys anymore (did my girlfriends and I really find those so pesky?), even when my kids aren’t with me. It seems a marriage, three kids, a career and too much life crammed into the last 10 years has finally caught up with me, making me feel like a Before picture.

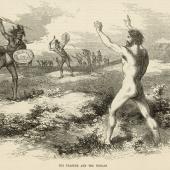

It was in this mind frame that I came across my old running folder, stuffed with racing bibs, marathon training logs, and yellowed newspaper clippings with my name and time highlighted. One of them was of the John Colter race, held every year at Missouri Headwaters State Park, near Three Forks, Montana. According to legend, Colter was stripped naked and chased by angry Blackfeet Indians across this arid land of camel-colored hills and rocky bluffs, on a path that crossed the Gallatin River. The race is supposed to retrace Colter’s journey—but with clothes and shoes.

I had won a third-place age-group plaque for running the seven-mile race in 64 minutes 10 years ago. Not very fast for having won an award, I thought, calculating my minutes per mile. Maybe I could beat it, kick that 23-year-old’s butt. The desire was enough to fuel the necessary trail runs until the first weekend in September arrived, when the race is held.

One thing had changed in the decade since I had run the Colter: there were more people. The registration form said they would close registration at 300 runners, and there looked to be that many there on the cold, sunny morning when I pulled into the parking lot. Many of them I recognized from the robust Nordic cross-country ski racing community the winter before; not a good sign.

I was 40 minutes early, using the time to make sure I was well hydrated yet didn’t have to pee, chugging water and in turn using the chamber pot I’d rigged in the back of my van, avoiding the Porta-Potty lines and obligatory visiting I was too nervous for. At race time I lined up somewhere between the middle and back of the pack, hoping this might allow me to pass rather than be passed. Then 300 people were suddenly moving as one plodding elephant, until after the first minute when the group transformed into a rattlesnake, the fastest runners up front like head and fangs, me back near the rattle.

The first mile and a half of the race was not on a trail, but was a flat road tour past the tiny industrial town of Trident, home of cement. Then the route became abruptly vertical, veering off the road and up a single-lane hiking path towards a bluff. There were entangled elbows and feet until people accepted their place in the pecking order, everyone charging forward for the first 50 feet or so until gasping lungs turned the line into a death march.

After a summer of running in the Bridgers, this forced walking frustrated me, made me remember being similarly trapped 10 years ago. Carnivorous sagebrush and rock scree surrounded the path, enforcing the single lane, until I noticed a few people busting out above me, scrambling along the sides like mountain goats, then ducking back into line. I took a deep breath and bolted, sprinting on all fours in spots, ignoring scrapes and passing a six- or twelve-pack of people until I felt like I was about to hurl, then excusing my way back into line until I could do it again-which I did, two more times until finally summiting the mammoth plateau.

On top it was rolling grassland, sweet relief, and everyone ran for their lives. I tried to match the pace, wondered if it was a bit much for me to hold as we ran up and down the restless sea. I relaxed into it, widening my stride on the downhills, imagining myself a deer melting into light and shadow.

I saw the husband of a friend and a doctor I know, gave them a cheery but apologetic hello as I passed them, my confidence dangerously boosted. I crested a hill then traveled down a steep ravine, saw a group of fierce-looking women ahead, taking turns passing each other. I picked up the pace, wanting to be one of them.

I pulled my gaze further ahead, saw what looked like a slightly smaller version of the mammoth climb at the beginning of the race, people walking it like ants in a line even though it was wide-open grassland, passing no problem. I had no recollection of this hill.

I slowed my pace in preparation, digging in with a choppy jog as I met it, the group of women hopelessly ahead. I reached the top feeling fatigued, and when I tried to open up to let the downhill take me, my legs felt as though someone from Trident had sucked out my quads and replaced them with cement. Plus there was something wrong with my stomach now, a burning up high like I had been punched. I grabbed a handful of flesh where it hurt and pinched hard, wondering how Cream of Wheat, banana, milk, and vanilla energy gel could betray me.

Racing is like childbirth-if you could truly recall the pain, you would never sign up again. In every race (and childbirth, for that matter) there is a period of time where I regret being there and wish I were anywhere else. That’s where I was.

I felt panicky, worried that I might have to walk, but dismissed it as impossible. Now each small rolling hill felt like a mountain, and several people passed me. Shit. Who cares; I’m too miserable to care, I thought. I could see the river teasing off in the distance and a water station just ahead.

“How much farther?” I asked, once in hearing distance of the station.

“Two miles, all downhill,” the man reassured me.

I grabbed a paper cup of water while still in motion, chugged it and winged it over my shoulder. I glanced at my watch, afraid to do it before. Forty-six minutes! I’d have to pull two seven-minute miles if I was going to break an hour. My first goal for the race was to beat my old 64-minute time; my second goal was to break an hour. Seven-minute miles would be fast for me, even on fresh legs. I picked up my pace, told myself I could survive two more miles. The downhill turned out to be a gradual up, and I thought mean things about the water station man as I tried to override the heaviness and fire in my legs, forcing them to go, go faster.

Then the trail went abruptly down, the kind of down where a practical person might consider things like knee cartilage, especially bounding down so recklessly. I saw one of the women from the group I had tried to catch earlier, now separated from her pack. I felt a surge of pride, sped up, and passed her as we approached the river.

10 years ago when I plunged into the Gallatin River it was unusually high, to my shoulders nearly, and I actually swam part of it. In this year of drought and fire the deepest section tugged at my knees as I tried to keep up a ridiculous-looking jog, scouting the crowd for my husband and sons.

Once out on the bank, funneled toward the finish line by a roped runway, the crowds went wild, clapping and whistling. I touched up my form a bit, then realized they were cheering a svelte woman, perhaps 10 years younger, as she made a show of overtaking and sprinting past me.

The large digital clock read 1:01:13 as I finished. My husband Steve and our sons were waiting as I collapsed on the park grass next to them. Steve handed me a Clif bar as the boys pelted me with voices.

“Mommy, did you win? That lady passed you.”

“We’ve been waiting a really long time. I’m hungry.”

“Good job Mom, even though you lost. A whole bunch of people were here before you.”

“What took you so long? Can we go home now?”

“Are you gonna eat your bar?”

I clapped as the officials announced the winners. The girl who sprinted ahead of me won third place in the 20-29 year old age group. I was pleased by the fact that I’d beaten my old time by three minutes, awed that this improvement placed me seventh out of 25 women in my age group.

No doubt much has changed since Colter ran at the Missouri Headwaters, when the prize was keeping his life. For one thing, there was a keg of beer and water jugs waiting. I hobbled over on petrified legs, thankful to be alive.

As editor emeritus at Montana Quarterly and the mother of three boys, Megan Ault Regnerus always wears clothing when running the John Colter race.