Montana’s Dog for All Seasons

Experienced hands learn to sense real prairie scorchers coming well before the mercury begins to climb. They feel the signs in the dry grass crumbling beneath the boot soles, the sound of insects buzzing, and the first tickle of sweat on the back of the neck. The heat was on its way, and all the hunter could hope for was a cooperative covey of sharptails before scenting conditions deteriorated or the long miles took their toll and he hit the wall.

Help stood by his side—Sonny, a blocky, broad-shouldered male yellow Lab. He could have modeled for a duck stamp portrait with a marsh in the background and a mallard in his mouth, but the vast expanse of hills and coulees stretching away before them didn’t hold enough water to make a bucket of mud. Even in his summer coat, he looked overdressed by several layers for the task ahead. What, a casual observer might have asked, is a nice retriever like you doing in a joint like this?

Plenty, as it turns out…

Montana’s ability to support a remarkable number of dedicated wing-shooting enthusiasts comes as no accident. In a world divisible into outdoor specialists and generalists, Big Sky country remains a delight for the latter. New England may offer more classical grouse habitat, the upper Midwest a few more pheasants, and all kinds of places a more predictable supply of waterfowl. But when it comes to doing as many things as possible with dog and gun, our own corner of the world has always been hard to beat. No wonder Montanans have developed a special relationship with one breed of dog capable of doing a little bit of everything or, in some cases, a little bit more.

A century ago, American waterfowlers hunted ducks and geese with the aid of Chesapeake Bay retrievers while upland gunners chased grouse and quail with pointing dogs. Divided by geography and taste, members of these two camps seldom met, and when they did, they usually passed like ships in the night. Leave it to westerners and their pioneering spirit to break down such distinctions. Our terrain and the wildlife it supports helped unlock the doors. Seldom have large populations of waterfowl and upland game existed in such convenient proximity. Then early in the last century, the western wingshooter’s upland options increased dramatically thanks to the simultaneous arrival of three imports from the Old World: Hungarian partridge, ring-necked pheasants, and hearty strains of wheat that provided a rich food supply for both. Suddenly, westerners could hunt more game bird species in one week than their eastern seaboard counterparts might manage in a lifetime, creating the need for a new kind of bird dog. Enter the Labrador retriever.

The history of the breed spans four centuries and multiple journeys across the Atlantic: from the original European St. Hubert’s hound to the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, back across the pond to England and salvation courtesy of a few titled British sportsmen, and back again to the early days of retriever trials along our own east coast. Throughout all, the Lab’s job description remained relatively constant: jump into the water and bring back whatever it was told.

The arrival of the pheasant in the American West changed the old formulas. In contrast to grouse, quail and woodcock, pheasants demanded a dog that could force birds into the air as well as reveal their location. Disguised behind years of service in the duck blind, the Lab turned out to be a natural flushing dog that also proved capable of running down crippled pheasants better than any of the classical upland pointing breeds.

In any biological system, periods of rapid change favor the emergence of new adaptations. In this case, the sudden confluence of Asian game birds, American hunters and wide-open spaces produced a new version of an old standby: the versatile flushing retriever. And no breed rose to the occasion quite like the Lab.

September, October, November, December… four months that justify the other eight in the hearts and minds of dedicated Montana bird hunters. Each means hunting different species in different ways, over a wide variety of terrain and climactic conditions. What an opportunity for a dog willing and able to do it all.

Hunting grouse and partridge in September means long miles across open country in summer weather… hardly the Lab’s classical job description. But despite their origins as seafarers, Labs do surprisingly well under hot prairie skies. They may not cover ground like the pointing breeds, but when the sharptails are holed up deep in the thorn brush, nothing gets birds airborne within shotgun range quite like a determined Lab. One caveat: while the breed tolerates heat better than its history might suggest, eager Labs can hunt themselves to the point of dehydration and collapse. During the early season, the hunter and not the dog needs to assume responsibility for canine welfare, which means stopping for water, rest and shade at reasonable intervals.

Come October’s cool days and splendid autumn foliage, the pheasant opener provides an opportunity for Labs to perform their best upland work, for nothing demands tenacity from a bird dog like wild Montana ringnecks. In contrast to grouse, pheasants would rather run than fly and typical Montana pheasant habitat provides plenty of room for them to motor, through tangles of cattails and thorns, across more vertical contour lines than most eastern bird hunters can imagine. Locating and flushing birds under these conditions demands a dog that won’t take no for an answer. An experienced Lab working pheasant cover represents a triumph of substance over style, as sheer determination eclipses the finer points of polished dog work. Both dog and hunter will have to earn their reward, but when it arrives in a burst of noise and color, the shot and retrieve will feel like a carefully scripted advertisement for the flushing Lab.

The pages of the calendar turn suddenly here on the high plains. By November, autumn’s golden hues have disappeared, replaced by snowy landscapes and the gloom of steadily lengthening nights. But those who love the outdoors find ways to balance the passage of every season. Now hope arrives on the wing as waves of ducks and geese ride the weather south from the Canadian prairies. Finally, it’s time for Montana Labs to become what their mothers intended all along: water dogs.

Labs function over a wider range of temperature than any other sporting dog, no small consideration in a setting that offers diversity of hunting opportunity as great as ours. But while Labs tolerate heat, they positively thrive in the frigid environment of late season waterfowl hunting, sitting patiently on creek banks with their muzzles coated in frost as they wait for an opportunity to plunge into water cold enough to suck the breath from human lungs. Credit their original physical adaptation to the maritime environment of the Labrador coast: sleek, water repellant coats, powerful swimming muscles, rudder-like tails, and above all hearts that refuse to let them sit on the sidelines for long. Technically, there isn’t a lot to shooting decoying mallards during the late season. Diehard hunters come not for the chip-shot gunning but for the spectacle: the winter sunrise, the sound of the birds, the cold light gleaming from the drakes’ emerald heads, and the magic of the dog. No one should spend a lifetime outdoors without enjoying an opportunity to watch a hundred-pound Lab launch from a high bank and enter a creek in a geyser of icy spray.

Technically, there isn’t a lot to shooting decoying mallards during the late season. Diehard hunters come not for the chip-shot gunning but for the spectacle: the winter sunrise, the sound of the birds, the cold light gleaming from the drakes’ emerald heads, and the magic of the dog. No one should spend a lifetime outdoors without enjoying an opportunity to watch a hundred-pound Lab launch from a high bank and enter a creek in a geyser of icy spray.

What a way to end the year.

Some Montana hunters run pointing dogs for upland game, and it’s hard not to admire their dogs’ style and grace. Others swear by Chesapeake Bay retrievers for serious waterfowl work, and a heroic Chessie performance in icy water can make anyone a believer. But day in and day out over the course of Montana’s generous hunting season, it’s hard to beat a Lab, especially for those who love to do it all.

Labs seem to be everywhere here these days, riding drift boats down trout streams and hanging their heads out of pick-ups to sample the smells of the road. A favorite local brew built its name brand recognition around the breed. (They picked the wrong color Lab, but the beer is too good to complain.) Given that our unofficial state dog used to be the Blue Heeler, this surely represents some kind of progress.

While a dog as versatile as the Lab makes a natural choice in a setting that offers such a variety of opportunity every fall, the breed’s popularity here derives from more than its utility in the field. From the size of our country to the chill of our winters, the demands of the western environment have always fostered an appreciation of good company, and no canine breed provides better. Labs always find ways to become friends rather than hunting machines, a distinction that explains why we miss them so once they’re gone.

Back in the heart of the sharptail cover, hunter and dog moved into position on the uphill side of a buffalo berry patch. At a single whispered command, Sonny plunged forward and assaulted the cover as if he knew the meter was running on his ability to scent game in the rising heat. How experienced Labs manage to worm their way unharmed through acres of thorns remains a mystery, but they do it every season, day after day, year after year. Driven by a primal urge to find and flush, the dog seemed to hunt without regard to the consequences of his own enthusiasm and moments later he generated his reward: a flock of sharptails’ politely staggered rise, the sound of two quick shots, and an opportunity to retrieve.

Of course that’s all hunting Labs ever expect.

The Once and Future Lab

For the last decade, AKC registration records have consistently proven the Labrador retriever the most popular dog in America. Not the most popular sporting breed… the most popular breed period, an amazing statistic considering that hunter numbers have generally declined at the same time. Credit the Lab’s functional versatility and the broad appeal of a canine personality characterized by loyalty, devotion, and eagerness to please.

But for some, it’s hard not to experience regret at the thought of all those potential hunters slavishly licking faces, boarding suburban SUV’s and following their celebrity owners down the streets of Los Angeles and New York, never to hear a shotgun bark or experience the feel of feathers in their mouths. Labs, after all, were born to hunt. Think of tigers pacing their cages in zoos—stripped of political correctness, the two situations seem equally pathetic. And the changing demographics of Lab ownership raise serious implications for the future of a breed whose unique personality reflects centuries of deliberate development for the sporting life.

As the Beach Boys once said of California girls: Wish they all could be Montana Labs…

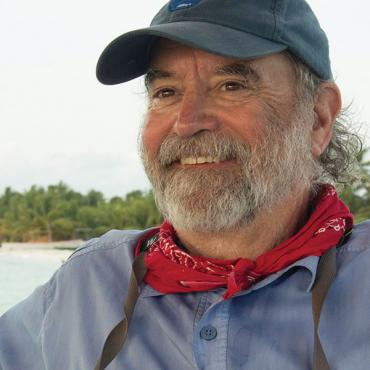

-E. Donnall Thomas Jr.

My Kingdom For a Lab: Life with the Hunting Labrador Retriever

by E. Donnall Thomas Jr.

Willow Creek Press

Anyone who has ever formed a bond with a good hunting dog knows that the experience is rewarding and adds an indescribable richness to life. Good hunting dogs oftentimes have the capacity to make better humans out of their owners. In My Kingdom For A Lab: Life with the Hunting Labrador Retriever, E. Donnall Thomas Jr. adds voice to what it really means to be a Lab owner and sporting-dog lover. Although much of this book revolves around the author and his dogs’ sporting forays in eastern Montana, Thomas also provides insight into the diversity and willingness of the Labrador to hunt in country varying from the Alaskan tundra to the African veldt.

What makes this book great is the way Thomas conveys the beauty and Zen-like harmony of hunting with a good dog. If you have never hunted with a Lab, the reading of this book may just have you browsing the puppy ads. Filled with great hunting stories, My Kingdom For A Lab also contains some helpful thoughts on training and some great information on the genetic history of the Labrador retriever. It’s a great read not only for the hunter and wing-shooting enthusiast, but also for the dog lover in everyone.

-Kurt Dehmer