Wade and See

Putting “guide-tested tough” waders through the ringer.

When you live in a place where spring is always late, you take comfort in the rituals of spring even though it seems a long ways off. This morning I’m preparing for another field season, and I enter the warehouse to take stock of our waders and boots to figure out what we’ll need for the coming year.

As I open the door, the smells of campfire smoke, outboard motor fuel, and neoprene mix together into the first hint of spring. Not that any of these alone have any meaning, but just that my being here means we are planning to go into the field. I walk to the cabinets and open the doors to see rows of waders in every shape and size, and most importantly, condition. As I inspect each set, I make mental notes: inside seams torn, barbed-wire holes in the crotch (damn, hope that didn’t hurt), ripped neoprene booties… the list goes on. We’ll be replacing most of them this year.

Maybe “guide-tested tough” means the manufacturer should put extra padding in the ass, because that’s what wears out first.

I follow the same procedure with the boots: missing laces, ripped sides, soles peeling off. All casualties of countless days in the field, hiking through brush fields and over fences, across log jams, up and down steep embankments, and always the tripping and falling over slick rocks that comes with any field work in streams and rivers. As I get to the last box, there’s a logo on the side that says, “Our Gear is Guide-Tested Tough.” I smile first, and then start to laugh. I wonder if they really have any idea of the difference between what a “guide” does and what people who work in this career field do. Probably not.

It seems there’s a romantic vision of the grizzled guide, living in waders day-in and day-out, in all kinds of conditions. My take, however, is that guides (at least those who are my friends) spend most of their time on their derrieres in a driftboat, with the occasional hop in and out to make lunch for their clients or land a fish. Folks, this does not put a lot of stress on your waders. Maybe “guide-tested tough” means the manufacturer should put extra padding in the ass, because that’s what wears out first.

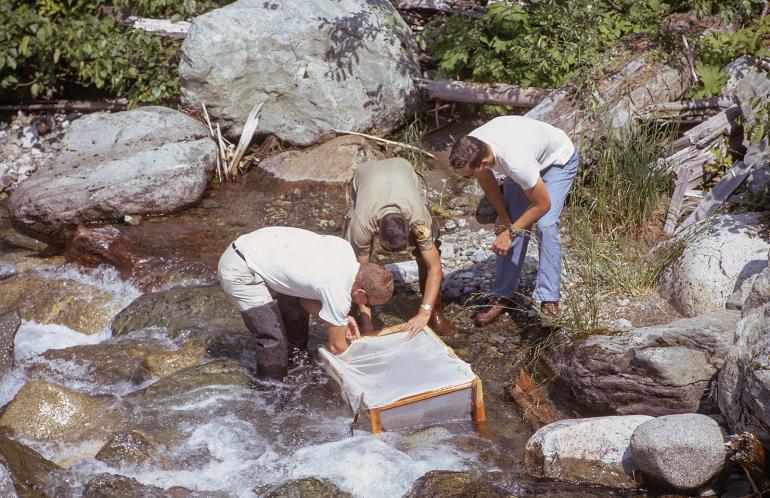

Field biologists tend to “test” their gear in a little different way. A typical day might be to drive to a field site, put on the waders, strap on a backpack electroshocker or field pack, hike several miles through mixed-brush fields and forests, and then spend the rest of the day doing surveys in the stream. Repeat the next day. I’ve watched field crews shred waders in a couple days in particularly nasty conditions. In fact, it can be downright scary in some cases.

A couple of years ago, we hiked into a stream to do some fish-population work. I had strapped on the backpack electrofisher, and the crews had grabbed nets and buckets. Everything was fine at first—the water was shallow and we moved slowly upstream collecting fish. Then, all of the sudden, we hit a hole that was a little deeper and one of the techs started yelling, “Shut that f---ing thing off!” and was running out of the water. It turns out he’d caught some barbed wire right at crotch level, and with water pouring in he was getting an unexpected thrill from the electrical field.

Now rips and holes are part of the job, and we carry patch kits to get everyone back up and working. But when you find waders that just don’t hold up, even when they are properly maintained, well that is damned irritating. I’ve had some interesting conversations with manufacturers about waders, and it’s almost as if they can’t believe their baby has issues.

I remember a conversation with a manufacturer a couple years ago when we sent ten pairs of waders back for the third time.

“Hi, I’m calling to get replacement pairs of waders for the ones that you replaced two weeks ago, that continue to have the same problem as last time.”

Sales rep: “Again? What are you guys doing out there?”

“It’s called field work. We put our waders on and hike miles into streams and do surveys. For some reason your waders start to leak along the inside seams about the third trip in.”

“Have you tried walking differently? Patching the seams with glue?”

“If there was any more glue on these seams, the waders would stand up by themselves.

Long sigh. “All right, send them back in and we’ll get the replacements out today.”

I’ve had the same conversation on numerous occasions throughout the years with multiple factory reps and many different manufacturers. To be honest, it has gotten better. Let’s look at a brief evolution of waders.

1960s: Rubber chest waders—easy to patch, but you looked like that tire cartoon character when you were trying to hike. At the end of the day you’d take the waders off and empty the four gallons of sweat that had accumulated.

1960s-70s: Coated nylon—about the most worthless pair of waders ever. Hard to patch, leaky seams, and good at most for two trips.

1970s: Latex, a.k.a. the human condom. These were originally latex rubber: lightweight, easy to patch like an inner tube, and ripped like hell. I remember walking into a creek to do field work, entering the stream, and feeling a cascade of water in my waders. Turns out I’d snagged it on barbed wire and run a rip down those babies from my thigh to my ankle. No patching when that happened.

1980s-90s: The neoprene revolution. Somebody got the bright idea of making waders out of wetsuit material. Good for the most part: easy to patch; kept you warm if there was a leak. Downside, see 1960s... I considered marketing these as a weight-loss plan after hiking a few miles on a hot day.

1990s-present: The breathable wader. A great evolution in waders—lightweight, easy to patch, cooler for hiking. Downside: like everything, quality can be a problem. “Breathables” that don’t actually breathe, or breathe so much you might as well be wet-wading. Bad seams, bad booties—the list goes on and on. But the biggest downside? Promising your first-born as collateral for the exorbitant prices.

Now I want to be honest, not every wader is a dud. There are some very nice waders out there, but when you are on a budget you need to balance the cost of a single pair of waders against buying 10-15 pairs for students and seasonal field techs. It’s pretty hard to justify the $350-and-up waders on a tight budget, especially when you add in the price of wading boots. The other thing is that different people treat their waders in different ways. Some folks can get through a field season and their gear looks like they just opened it, while others have gear that looks like it is ready for the trash after the first week. That is just the nature of people. We are all different.

So the next time you see a label that says “Guide-Approved” or “Guide-Tested,” you may want to call your local biologist and get the real scoop. Unless, of course, you need extra padding in the rear.