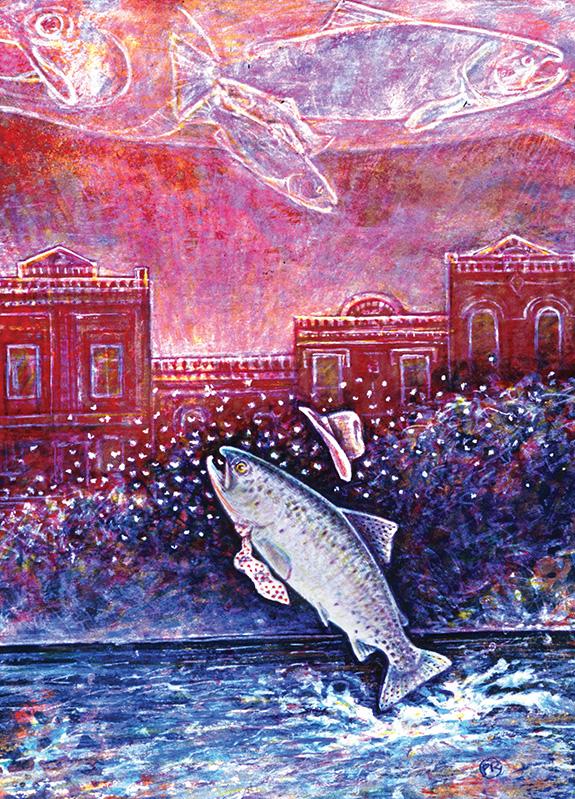

Some Town Trout

Finding one's place in the grand stream of things.

On evenings when the spring thaw is going full blast, I like to sleep with the bedroom window open. Though I live just two blocks off Bozeman’s Main Street, I can hear Sourdough Creek swollen and roaring down from the Hyalites where elk are dipping for a drink, down through hay fields then subdivisions then the older tree-lined streets like my own then under the heart of the town then out to join the East Gallatin, the Gallatin, the Missouri, the Mississippi and the Gulf. Drifting off to that sound, I seldom remember my dreams, but my waking thoughts are as diverse as the way light hits the water when I watch from a bridge half a block from my house.

Figuratively, my friends and family have been woven into that sound over the past eighteen years, and literally the beautiful brook, cutthroat, and rainbow trout have occupied the stream’s small wilderness as it mocks the brief civilization through which it passes.

When I first moved here, I was barbaric enough to try to catch them. I skulked through the backyards of condos and fourplexes, an Okie astounded that such pristine water could keep its cool in the middle of town, my fly rod held low so as not to be seen from picture windows. Dangling an Adams, a Trude, or Joe’s Hopper as the season required, I caught amazingly fat and bright trout that took my fly without question. As these porcine brookies flashed down the delicate riffles and behind the undercut banks, I knew I hadn’t lived a decent enough life to deserve a place like this.

And it was true. I was totally out of bounds. One evening a kind but panicked woman came striding across her back yard to inform me that I had just caught Helen, a trout whom she had befriended to the point that it would dart to a certain part of the pool to be fed Green Giant corn niblets. Dejected and ashamed, I released Helen while the woman warned me that only children under 12 could legally fish in Bozeman city limits.

It wasn’t until a few years later, when my younger son was old enough to use a rod, that I dared pursue these trout again, guiding him and his friend down the grassy paths next to the stream, but even then, to be legal, my fishing thrills had to be vicarious, and soon the boys realized that they weren’t so much experiencing quality time as being used as an excuse for a pathetic adult to act out his streamside fantasies. Besides, they were just flirting with the stream and they wanted to have their way with it – like my older son who had donned cutoffs, hopped on an inner tube, and floated its mysterious tunnel under Main Street.

Several years after that, Richard Brautigan, who was teaching in my department at the university, suggested that we paint plywood cut outs of young boys wearing straw hats and holding weeds in their teeth and hide behind while we fished. But, as usual, we wound up sitting in the Eagles bar and drinking George Dickel instead. In a way, this wasn’t too far from the original plan because Sourdough Creek plunges under Main Street just a few feet west of the bar. In the spring, when the place is almost empty and the jukebox isn’t going, you can hear it.

That sound holds more now than it did then, and at night when I’m lying in bed it almost carries too much. My sons and their friends have grown up; Richard shot himself a decade ago; two girls drowned under the Eagles after a night on the town. The fish are still beautiful but not so much fun anymore. Even the caddis fly hatches seem a bit dazed and confused when I stand in the front yard and watch them in the evening. Across the way, Earl, the retired county surveyor, surveys them with me while they dance over the street as if it were water.

Chances are, they’re not confused at all. Behind my house, the alley is strewn with rocks from the old stream bed where it probably flowed a thousand years ago, and I’m sure the relatives of those flies have danced for millennia back and forth over the valley where geology and the weather chose to move the party, the cutthroat trout leaping up through the dance in their own sweet time. These street flies are obviously playing a trick on me and Earl, dancing a few centuries out of place.

Or maybe we’re just learning to read. Perhaps trout, bugs, and moving water are print in the book of our place. Downstream where Sourdough runs a few feet from the public library, my wife spends much of her time reading books and water, glancing down then out the window, confusing words with the light and sound which inspire them, and when I think of this, all the loss and transience seem only natural.

Soon Sourdough will be clear enough for fishing, but I won’t attempt it any more. Instead, I’ll catch grasshoppers and drop them from various bridges while I walk upstream toward work. Perhaps I’ll look silly to passing bikers and joggers as I hunch and pounce in the grass, my sportcoat hung on a branch above my briefcase; but if they’re foolish enough to question me, I’ll give them a brief reading lesson and make them watch a grasshopper drift until a delicate nose breaks the surface.