Reading the River

Approaching a beautiful Montana stream for the first time, the awestruck angler may assume that in that cold, clear water, below the towering trees and lush bands of greenery, the fish are everywhere. Simply toss one’s fly, lure, or bait into the current, wait for a strike—and then set the hook on a fat, feisty trout, its silken skin glistening in the sun as it leaps once, twice, three times, before sliding sideways into the net.

And surely this happens—sometimes. Other times (most times), the unfortunate dreamer spends far too much time casting into water that holds no fish, and thus no hope for the aforementioned experience. Like all critters, trout have specific habitats: places that maximize comfort, safety, and convenience. If you want to spend more time catching fish, and less time wondering why you’re not, you need to know a few basic rules of the river.

Current

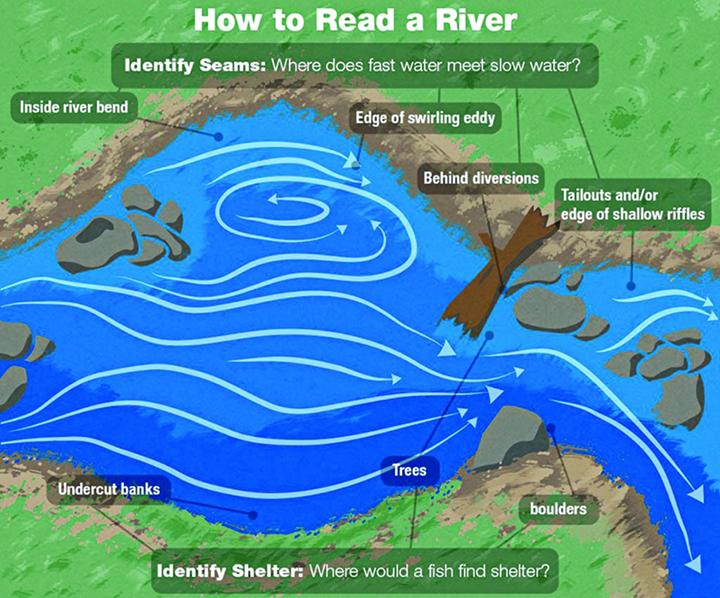

Pay attention to the speed at which the water’s moving. Trout prefer a moderate current: not too slow, not too fast. Slack water doesn’t have the oxygen content or as much food flowing downstream; rapid flows require too much effort to stay in the current. Look for transitions or seams, where slower water and faster water merge; the trout will often lie just inside the slower water and dart out into the faster water for opportunistic feeding.

Cover

Ospreys, eagles, otters, coyotes, humans—the river teems with threats to a trout’s safety, and it learns from a young age to stay close to cover. Undercut banks, overhanging brush, downed trees, boulders… all of these give a trout a sense of security and an opportunity for escape. Open, shallow water under the midday sun? Not so much.

Features

If you do nothing else, fish the features. Look for holes, bends, runs, eddies—anything that breaks up the uniform flow of the river. Start with the obvious spots: a deep pool below a fallen log, the roiling drop-off under a riffle, swirling pockets in a rock garden, a long trough of deeper water. Focusing on these features will produce more fish than indiscriminate casts into open water.

Exceptions

Finally, a caveat: trout are unpredictable and may violate all these rules. I’ve caught rainbows in four inches of slack water at high noon, and plucked fat-bodied brown trout out of raging currents where I couldn’t see or feel my line. Fish do, in fact, live everywhere in the river—but they pile up in certain places, and the more you center your efforts there, the more you stack the odds in your favor. However, if you see a blunt nose poking out of a stagnant, wide-open slough, throw all these rules out the window and send your fly, ever so carefully, into that watery world of infinite possibility.

Mike England first fished the rivers and streams of southwest Montana in the late ’70s, when the Gallatin Valley had more 18-inch trout than people. He is the editor of Cast.