A Horse for Clare

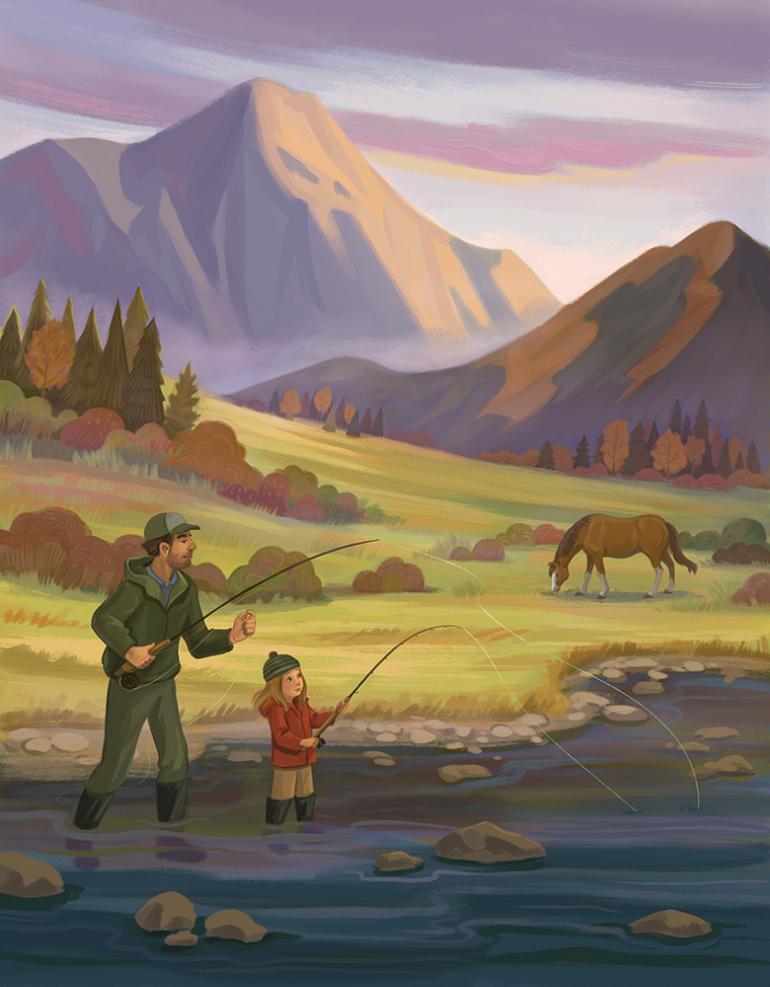

Raising a daughter in the mountains of Montana.

When you were tiny and squalling, I carried you out to the horse pasture and we stood among them and listened. As soon as we were in them, among them, you quieted. Switched off the noise, turned on the attention. As they grazed and we smelled them. There’s nothing like the smell of horses.

You would point a tiny finger at each of the horses.

“That one.”

I would walk over and place you on an equine back. Hold you there. If the horse walked off, I still had ahold of you and we could move to another horse. No halter, just horses in a pasture, smelling a little girl in my arms and you smelling them back.

Usually the horse did not walk off. It knew. Old Mac, all of twenty-eight and long retired.

“That one.”

Big Red, way up there. Holding on tight, two tiny fists tangled in mane. A massive, powerful horse usually charged with lightening but quiet as an old dairy cow when a child was aboard.

“That one.”

Good, gentle, homely Marv.

“That one.”

Black Jack, impressive flowing mane, coal-black hide.

We would walk among eight horses and you would be astride every one of them, if only for a moment. The eighth horse, the one that seemed extra special—and always the final one—was June.

She was born on this ranch in the heart of June, a colorful little filly with good breeding and fine long stockings and a big wide blaze. Trademarks of her line, those markings. Put together well. I named her Calamity June. She is grown now. She will not be very big, but she’s as pretty a horse as I have ever raised. “That horse is going to make a little girl really happy some day,” a friend said to me once. I thought to myself, “I know just the girl, a little calamity in her own right.”

Early on, I had designs for June, thinking, maybe, that she’d be a horse I might ride one day as my new number one. But she did not grow much in that first year or in that second or even in that third. By the time I started to work with her in the round pen, she was a nice pony-sized horse. Too small for a man. Just right for a little girl, a little girl who calls me Buddy. Just right for you.

You and I met on a river.

Cold water. Clear. A river of trout and the promise of day.

Your mom went into the hardware store and left me to watch you, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed beauty who was not even two. No problem. But when you projectile-vomited because Mom was gone for fifteen minutes, doubt crept in. I do not get along well with human vomit.

Your mom has the prettiest fly cast in the land and can row a drift boat with flawless precision. She is as good a rider as I have ever seen and I taught her to tie a basket hitch in only one showing. But barf before breakfast, before the boat was even on the water? I didn’t know.

Then we were with the river and the wailing that would have shamed a suckling pig turned into happy babble. Chatter. A switch had been flipped. The river took us from the boat ramp, over cobble and sand, down riffle. We landed on a midstream island and cast nymphs into a run and you tottered on the bank and collected rocks. I caught one nice rainbow, then put the fly rod in the boat and helped you find heart-shaped rocks. The fishing was forgotten.

We have been aboard that boat many times and it is always the same. Horses too. Walk among them and sit astride them and it is as if you have climbed to a new plane, a new plateau where the loudness of the world is forgotten. Horse and girl live here and it is magical. There is peace here.

I think about the children of this country sometimes, especially when I see them in our cities. Most have their heads down and don’t look where they are going. The adults are like this too, pounding the sidewalks, engrossed in text messages or yabbering on phones. Earth rotates. Humans mutate.

We go camping. We look at the night sky. You lie between Mom and me in a chaotic nest of blankets and sleeping bags, watching for falling stars. In the morning, we get up and you run around half-naked and cover yourself in dirt then rinse off in the tiny stream near camp. We look for bugs and squirrels and wildflowers growing in wet edges of meadows. We walk the pines and happy prattle comes with us.

Back in the truck and then back home, plugged in, carping and discontent. A pattern emerges.

You were just a toddler when you rode a horse with your mom for the first time. You both got on Marv and you rode up the ranch road and you waved to the camera. All any of us could do was smile. We got you a pink cowboy hat and pink chaps and you were styling. You still wear that hat and those chaps and you go out to the barn and climb into a saddle in the tack room and pretend that you are roping a cow when you are roping compliant farm dogs.

We spent your third birthday on the river. We cooked a birthday cake in a Dutch oven over coals of fir and alder, listening in the fading day to the river toss and turn on its limestone bed. That day, your favorite present was a skwala stonefly that crawled up your little hand onto your arm and a red heart-shaped rock I found on a gravel bar. Turning three outside. That’s the way to celebrate a year gone by and a year coming on.

You’re four now and you remember where you were on your third birthday and you can remember that first ride. You talk about skwala presents and heart-shaped rocks and when I am out in the field, walking behind a gun dog, or riding Jack up a ridge that whispers to me of bull elk, I think of you. Sometimes, I’ll find a pretty rock and put it into my pocket or my saddlebag and bring it home. On a river this summer, I found the top half of a mussel shell, polished and glittering like an oyster shell from the ocean. You laughed when you saw it and asked me, “Buddy, an animal lives in there?”

“Yes, honey, that was his home.”

This is my first go-round in helping to shape a human life at such an early stage. Maybe I’m not doing it right and maybe I’m making all kinds of mistakes. But when you scrape a knee from falling off a buck-and-rail fence, or get a splitter after playing in the woodpile, or a rash on your butt from sitting bare on a bale of hay, I somehow think of those wounds as cleaner, more honest than those of the city kids. Maybe I’m wrong.

But I think there’s a rightness in the way of the soil. I think there’s something to be said for a life being jostled by a pack of bird dogs or nuzzled by a herd of mountain horses, climbed by the barn cats, pecked by hens on the nest. When you bury yourself in black dirt to your little elbows in the garden helping Mom, or construct castles in the sandbox nearby, I know a happy kid when I see one. Inside four walls, you glower. Outside, you glitter. You ask to go horseback riding and fishing and camping. It doesn’t matter if the stream is the one that runs through the ranch or the camping is in the horse pasture, or the horseback riding is in the corral. It is outside and you ask. I love that.

So I am working with June and making sure she will be safe for a little girl to ride when you are old enough to ride her on your own. I see a day when our family goes into the mountains for a long week of camping and horseback riding. In that dream, I see you on June, smiling, riding your own horse, crossing rivers and bridges. I see you as a tough Montana girl who has the whole world ahead of her and believes she can do anything because she’s mounted on a good horse and she has the trail ahead. There is nothing but trail ahead.

Some day when the world comes up to greet you outside this place, you may not know a salad fork from a dinner fork and the plugged-in world may be a foreign land. But you will know how to throw a double-diamond hitch on a pack horse, find good feed for your herd in the mountains, work the clutch on an old Ford, row a boat, cast a fly line, swing a shotgun. You’ll know where to put the crosshairs and when the job is done, you’ll know where to start with the knife. You will know a good horse when you see one and you’ll have enough common sense to pass on the bad ones. You’ll know how to bake a cake in a Dutch oven and clean a mess of brook trout for dinner. And you’ll know that there are stars in the sky and you will own a horse named June to ride beneath them.

Tom Reed is the author of Blue Lines: A Fishing Life. He lives in Pony.