Royalty in the Batholith

Climbing the King & Queen.

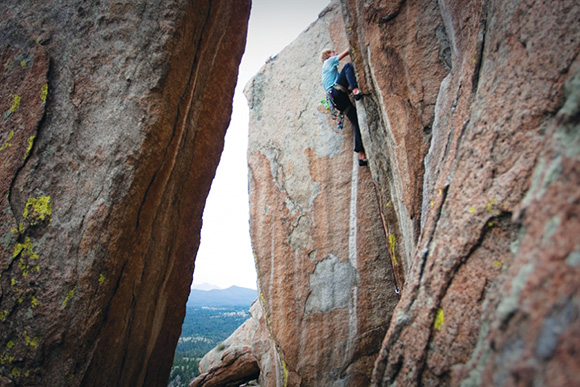

From the interstate, the King and Queen stick out like a wart in the wooded hillside of the Boulder Batholith. With little precipitation and drive-up access, this multiseason crag boasts great camping and beautiful towering walls of granite, riddled with fissures, cracks, and weaknesses—some big enough to hold gear, some not. Most aren’t. I’m somewhere in the middle of a blank face, scanning the same piece of rock again, neurons firing like handguns, sweat percolating on my brow in staunch denial of the crisp spring temps. “You alright?” my climbing partner calls up. “You haven’t moved from that spot in about ten minutes.”

Climbing up here has an old-school feel, imparting the sense of adventure that just isn’t present in crags developed in the last decade. It’s not that difficult to pull the moves, but it can be difficult to move above the gear—requiring a mental fortitude that they don’t list as “recommended equipment” in the guidebook.

The clapping flutter of bored pigeons 100 feet above rattles me. The climbing here, it demands care and precision. Every. Single. Movement. In a world of drive-thrus and emails, dedicating yourself like this feels refreshing. It’s immediate and it’s real. Pulling down with my left hand, a wafer of granite snaps off and a tidal wave of adrenaline flushes down my spine, forcing me to suck back a lungful of clean air as every muscle clamps down. Fight or flight. Literally.

Behind me, the Jefferson Valley under a glacier-blue sky. If you ever climb here, just remember that any rock east of the Continental Divide qualifies as outside Whitehall, not outside Butte. “Here in Whitehall, we piss and it goes to the Atlantic,” a drunk local told me the day before. “Butte piss goes to the Pacific. Get it right.”

The granite walls of the Batholith were scaled long before “climbing” became a sanitized yuppie health craze, so the rock features captivating distances between points of protection on routes. The bolters here weren’t masochistic, just realistic: if a route has 15 or 20 gearless feet where an average climber wouldn’t fall, there won’t be a bolt. Simple as that. A slip just under the chains might plant you right on top of your belayer’s head from 50 feet up—but if you don’t fall, no worries. So don’t fall. And if you make it to the top, remember: whoever climbed this first, they did it using gear so ancient you'd laugh.

After scrambling up the final few feet and clipping into the chains on a small ledge, the fire of my focus smolders down to embers. A few pigeons explode out of a seam and rocket out into the valley. I grab the chains and lean back to scan the rock above, and I see something foreign: a small plaque—black tombstone granite shimmering in the cold daylight, 80 feet off the ground. Hanging from four thick steel bolts drilled into the brown rock, it says, “KEEP CLIMBING” and gives tribute to a local legend who passed in a climbing accident on the Grand Teton.

Thousands of people might see his grave. But between now and whenever, maybe only a few dozen people will ever see this.

But that number doesn’t matter. Only the right people see this.

So I take a deep breath. And keep climbing.

For info, route descriptions, and an area history, check out Butte’s Climbing Guide by Dwight Bishop from First Ascent Press.