Raw Exposure

A candid account of climbing on Mount Cowen.

Our first trial arrives at the trailhead. It’s not clear whether we’re still on the road or in a pullout; a few cars are stationed irregularly across the uneven dirt so we park it right there, just shy of a decadent gate with a code box and a Forest Service trail sign. Our car’s thermometer reads just shy of 90 degrees: about right for an afternoon in late August. The air is laced with smoke and we hope to get above it soon. Packs on the shoulders, boots on the ground, march. The trail heads east and after a brisk mile, we realize we are making a large circumvention of a private ranch.

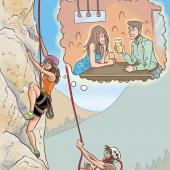

The flat three-mile horseshoe route puts us back within a mile of our car, and we start walking uphill. Sweat simmers off our brows and every so often, a pair of climbers appear, walking down the trail. We don’t need to ask; their facial expressions tell the whole story. Desperation, jadedness, wanting to be done, fully saturated with awe and admiration. We walk a long ways uphill, then start walking back downhill. Reaching Elbow Creek, we turn uphill again, relieved. We’re closer than we’ve ever been, no matter how far we have left to go.

Arriving at Elbow Lake around dusk, the choicest bivy spot is already taken. We slump out of our packs and bust out the stove for some heavily seasoned rice and undercooked lentils. You can, in fact, cook rice and lentils together, so long as you have a taste for undercooked lentils. You will pay the price the next morning after your strong cup of coffee, but you’ll be glad to get through that part of the day quickly.

"After futile attempts with his hand, my partner opts for an alternate strategy: reaching out foot-first. He presses into the seam with both hands and jams his toe into the slightly too-small crack. He's fully committed."

At the crest of dawn, two headlamps are zig-zagging through talus across the lake as we sling up a shoddy bear hang. We don’t have time to make it bombproof; we need to catch and pass them. But they’re too far ahead, and we’re scooped. The pair is racking up slowly at the base of the Hooven-Leo variation—the most common three pitches to start the Montana Centennial Route. We know we can rack up faster, so we ask to play through and our request is denied. We could just do it anyway, but asking in the first place was out of line. We hike around to the original start, guarded by a fierce, poorly-protected third pitch. I draw the short straw.

As I leave the relative security of a thin finger-crack, I reach for my RPs—small stoppers made of malleable brass for extra bite into the rock. I place two in the top of the crack before traversing right with my hands underneath a roof, moss and sand preventing my fingers from finding good purchase. Focus on the feet. Don’t think about the RPs; they are behind you, in the past. They fade into distant memory as the committing move approaches, a karate-kick step across a slabby corner. Deep breaths bring calm. I almost close my eyes, but not quite, as my right foot smears onto the other side. We’re in the thick of it now.

A few more pitches of beautiful crack climbing lead us beneath the crux. It’s Ben’s turn, and he makes short work of the wide, wet climbing on the pitch’s first half. He pauses before the hardest moves. A thin seam tapers to nothing, where an off-fingers crack just out of hand’s reach begins to the right. I wonder how long he can hang onto the seam—he looks like he doesn’t want to find out. After futile attempts with the hand, he opts for an alternate strategy: reaching out foot-first. He presses into the seam with both hands and jams his toe into the slightly-too-small crack. He’s fully committed. As if he were the lovechild of a gymnast and a ballerina who somehow found his way onto the Western Beartooth skyline, Ben sticks the move and dances through the rest of the pitch. We are over the hump.

Above the crux, we get off-route, climb an extra pitch, get lost finding the rappel anchor to a notch, scramble down a steep cliff beneath a gully to find a casual ramp not 100 feet beside it, walk back to Elbow Lake, puzzle over why we’d hung our bags when we didn’t even have any food left, and make it back to the car well after dark. There is no room for embellishing the experience of climbing on Mt. Cowen. There is only the pair of climbers, and what happens out there. If you want to find out for yourself, bear in mind: this mountain will test you. Be ready to ask for some extra credit in blistered feet, dehydration, and a long drive back to town, ‘cause you’d be crazy to go back for a retake. But we’re all a little crazy, aren’t we?