Between a Rock and a Hard Place

“Climbing!” I yelled as I began my ascent up the side of the canyon. It was a beautiful afternoon, after a night of unrelenting thunderstorms; we were all covered in mud from the scramble to “our spot” and were stoked that the south-facing rock was dry. It was an extraordinary afternoon; the canyon had a special glow and you could feel the positive energy emanating from the rock. Looking across the canyon at snow-capped peaks and heavily timbered ridgelines, we all could truly appreciate the vastness of the Rockies and recognize the privilege of being a part of it. Climbing these sheer cliffs and enormous mountains provides a sense of the intangible spirit of nature and an awareness of the essential facts of life—those simple smells, sounds, thoughts, and emotions; things we all forget about while stuck in our modern technological world.

Thousands of years ago, someone must have realized this connection between man and nature through the ascent of mountains, deeming them a sacred place, a place to build altars and be one with your surroundings. This feeling of sacredness still dwells on the tops of mountains and has drawn people to climb them since the beginning of time. Originally, it was for some cultural, religious, or practical purpose; rock climbing as a sport is a fairly new idea. In 1786, a few of the first few climbers, Jacques Balmat and Michel Paccard, completed the historic climb up Mount Blanc. With that boost it became more respected and climbing has been gaining popularity each generation since. In fact, that brings us to today, the “golden age” of mountain climbing—thus named because of the amount of interest, the number of professional guides available, and the new accessibility to it with rental gear and indoor gyms.

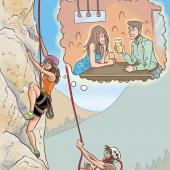

Learning to climb is very much like learning to ride a snowboard—picking up the moves isn’t hard, but perfecting them could take a lifetime. Every situation in rock climbing is different; every rock, every move, and every change in weather demands a different kind of action. This knowledge can only be acquired by experience in a practical situation, preferably with someone more qualified than yourself. This is beneficial for a multitude of reasons and any good climber will credit some of their success to a more experienced partner. On the rock, your skills and determination can get you to the top; but if you fall you’ll have to trust your climbing partner with your life. This kind of trust makes for very strong bonds and relationships and solidifies the notion that climbing is both an individual and social sport.

Climbing is all about balance, about knowing your body and being able to reposition it properly on the rock beneath you. It’s about concentration, overcoming your fears, and learning to adapt to what the rock has to offer. It’s important to realize that you don’t need to be young or extremely fit to pick up climbing. There are excellent climbers of all ages; in fact, many people start later on in life. However, if you are eager to learn, enthusiastic, and in reasonably good shape, succumb to the mountains and experience the purity for yourself.

I made it to the very top of the climb that day. Standing atop the spire I was overwhelmed; not with the usual feelings of accomplishment, but an indescribable feeling, one I’d never experienced before. It was an untainted sensation of absolute contentment. For a split-second I felt as if I was connected to the earth and free from the “real world.” The combination of fascination, challenge, and thrill is one that only climbers experience—those of us lucky enough to temporarily leave the real world behind and make our way, one move at a time, toward the sky.