All the Wall Is a Stage

Performance anxiety in the climbing gym.

This problem is giving me problems. I’m not keeping my core tense enough as I shift my weight from right to left, so my body swings away from my hands and I fall. Plus, my arms are getting pumped, so if I don’t send on this attempt, the chances I do on the next are slim. I visualize my first few moves: crimper to side-pull, shift right hand to the hold vacated by my left, feet shuffle to lock into toeholds. I just barely resist the urge to mime the lateral move with my hands, Adam Ondra–style—I don’t want the musclebound girl two feet to my left, or the bespectacled guy on my right, to think I look stupid.

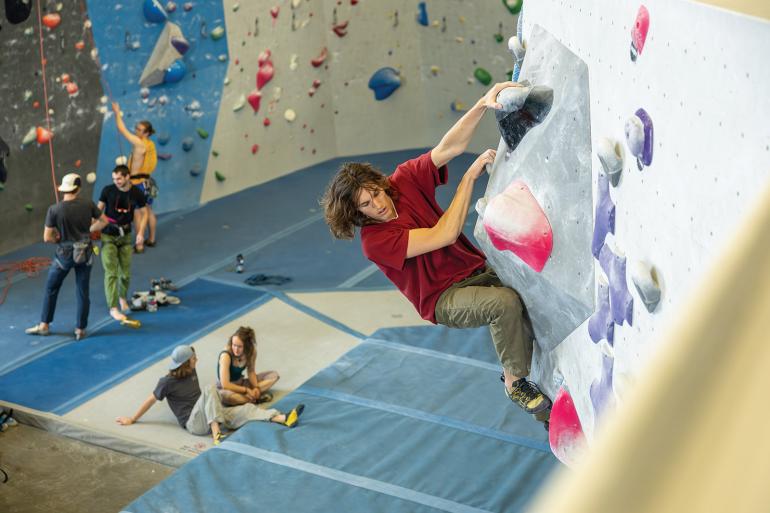

I rise from my bench, and as I approach the boulder—er... 12-foot-tall synthetic wall—I feel the eyes of Musclebound and Specs on my back. They’re watching, as are the high-schoolers milling around behind them, the dad and his kids taking a water break on the mat, and, at least in my imagination, every other person packed into Spire at 6pm on a Wednesday. But I’m cool as a cucumber.

I’d much rather celebrate others’ successes rather than their failures. But I find that when climbing, it doesn’t matter how high I am—just that I have someone to look down on.

I dip my hands into my chalk bag and place them on my starting holds—big hunks of bubblegum-pink plastic that make the term “rock climbing” somewhat dubious. I take a deep breath and cough up the chalk I just inhaled, clouds of which mingle with ashy flakes of skin to give the air a thick, almost opaque quality. Then I clench my fingers, tense my stomach, and lift my body off the blue crash-mat. Two feet to my left is my objective, a pink half-moon side-pull, but already my strength is fading. I know I can’t hang here long, so I lunge for the half-moon but overshoot, slamming my fingernails into the wall and scraping skin off my knuckles before thudding to the ground.

It’s hard to get up gracefully when you’re lying on your back like a turtle. Do you roll over to one side? Try to turn it into a backwards somersault? Go for broke and try a kip-up? I opt for the backwards somersault and regret it immediately, then sneak a peek at my audience. They pretend they weren’t watching.

With its high canyon walls, hard rock, and romantic solitude, it’s easy to see climbing as a purely physical, maybe even spiritual, act. But when you remove the dramatic imagery and take the sport inside, it looks a little different. Rather than watching shadows dance on a rock face or a hawk soar high in the canyon, we watch each other, and climbing in a gym often feels like an exhibition sport—one in which we’re constantly comparing ourselves to our neighbors.

Every route in a climbing gym is brightly colored and labeled according to difficulty: roped climbs on a scale of 5.0 to 5.15 and boulder problems on a scale of V0 to V17. Without these identifiers, we’d be lost navigating a rainbow of plastic. But I find that the grading system makes my successes—and failures—much more visible than I’d like. With the bright labels and close confines of a climbing gym, I feel like I’m walking into the Roman Colosseum full of gawking spectators, and they want blood.

Yet I’m as guilty as the next person.

I reclaim my seat on the bench and take a long draught of water while a long-haired kid, probably from the local high school, saunters over and floats up my V4. I watch his smooth movements with envy. Then my bench-neighbor, a tall, long-armed fellow with long hair and short shorts, rises to approach the wall. We have a similar build, long limbs and slim torso, which is a formidable build for climbing, so I expect much from this hairy-thighed hombre, but he settles into a V2 that I warmed up on and sweats and strains his way up the wall. I feel vindicated, and silently thank Thunder-Thighs as he huffs back to join me on the bench. In a climbing gym, your weakness is my strength.

Schadenfreude is the pleasure derived from someone else’s misfortune, and I rarely feel it so keenly as when I’m gym climbing. It’s an ugly feeling. I’d much rather celebrate others’ successes rather than their failures. But I find that when climbing, it doesn’t matter how high I am—just that I have someone to look down on.

I make excuses. I’ll say things like, “That’s a spicy V4,” and I’ve developed a bad habit of looking down at my hands after slipping off a hold as if they’re the ones to blame.

Climbing—bouldering especially—is designed to make us acutely aware of numerical signifiers of success. Lots of chatter in gyms revolves around this topic, and on any given day at Spire you’re likely to hear things like, “The V4s here are stiff,” and “Oooorrgghhhhh,” and, “How is that a V5?”

Rather than accept my failure to climb up eight feet, I dissect the route and make excuses. I’ll say things like, “That’s a spicy V4,” and I’ve developed a bad habit of looking down at my hands after slipping off a hold as if they’re the ones to blame—the climbing equivalent of furiously chalking a pool cue after a bad break. It doesn’t make sense, but I do it for my audience.

Back in the Colosseum, I’m locked in mortal combat with another climber. It started with us taking turns on the same V5 and quickly devolved into a cage match, going blow-for-blow on our mutual project to see who sends first. There’s a veneer of politeness—after a failed attempt, I sit down quietly and wait my turn—but we’ve become sworn rivals, and as I watch him climb, I’m praying for a toe to slip or his finger strength to run out.

We’re mirroring each other’s every move, like Rocky and Creed, or Ali and Fraser. It’s a prize fight and we’re going punch for punch. As I’m about to deliver the death blow, a soaring dyno where my long arms give me an advantage, he turns tail and leaves, apparently unaware that we were gladiators.

Watching his retreating back disappear into a haze of chalk, I wonder if not everyone thinks the way I do. Many people probably come to Spire for easy exercise after work or class, or they meet friends there to cheer them on as they sweat out their latest projects. I might be projecting, and people watch me indifferently or don’t watch me at all when I climb.

But I can’t be the only one. I dream of a better world, but for now, I live in the Colosseum. I’m working on my judgement, trying to beam compassion and love to my bouldering neighbors, but for now, I still feel a little pleasure when someone falls off the wall. The good news is, I have only one way to go, and that’s up.