Protons and Pitons

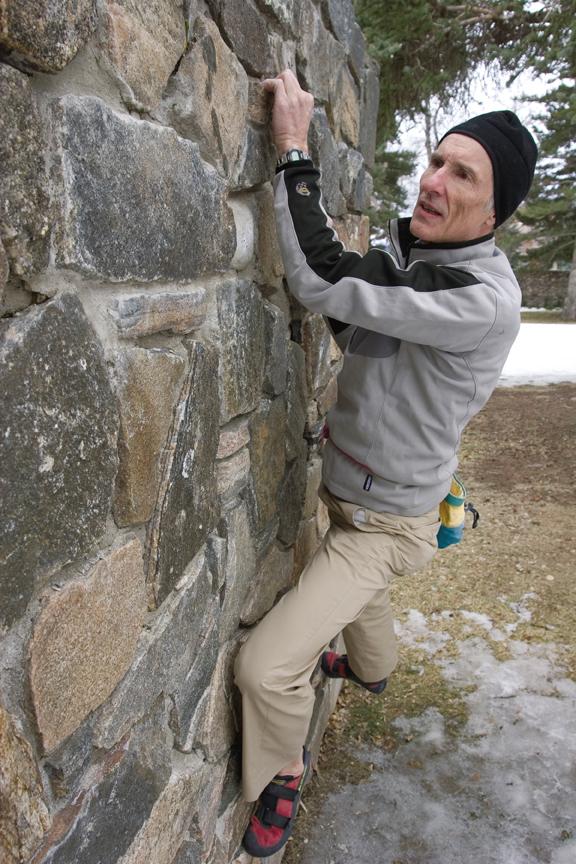

Portrait of a climber.

We Montanans are not generally known for our exceptional water polo players. Nor for our contributions to the beach volleyball athlete pool. The Big Sky state tends to produce athletes and adventurers of a different type. With such unique geography and environmental challenges, our athletes have skill sets outside the normal. We scale sheer granite cliffs via a slender crack. We skin up and ski down 10,000-foot peaks. We paddle Class V rapids. In short, we are badasses.

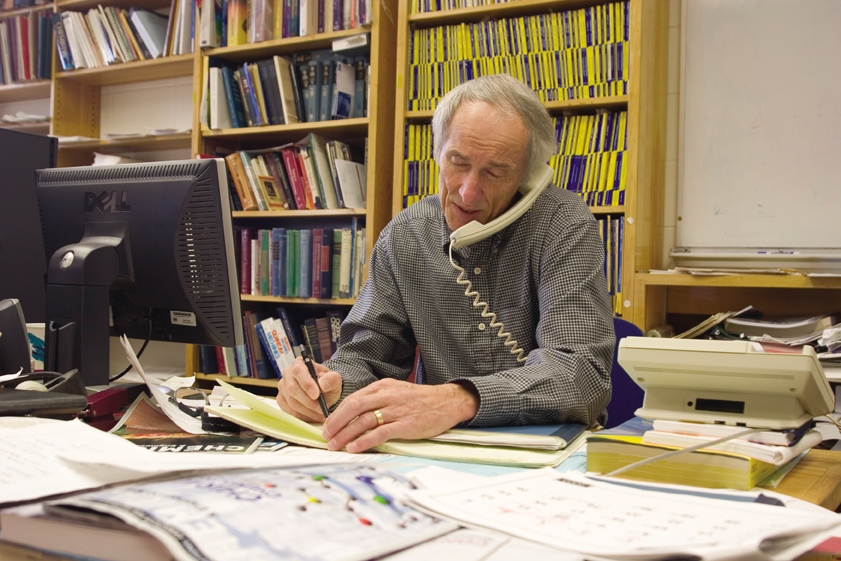

Pat Callis is one such badass. A chemistry professor at Montana State University, Pat is also a pioneer of ice, rock, and alpine climbing in North America. Originally from Oregon, Pat moved to Bozeman in 1968 by way of Washington and California, and has helped develop and sustain rock and ice climbing in Southwestern Montana for decades of climbers to enjoy. Pat likes to joke about “being famous for being famous” more than any climbing feats he’s actually achieved. However, a look at Pat’s alpine resume reveals the true identity of the extremely modest scientist and adventurer. The first recorded ascent of the north face of Mt. Robson in the Canadian Rockies and numerous first ascents at Suicide Rock in California are a few of his major accomplishments outside of Montana. Local fame credits him with classic rock climbs such as the first free ascent of Theoretically in Hyalite Canyon and Sparerib in Gallatin Canyon, as well as Cleopatra’s Needle, the famous waterfall ice feature in Hyalite Canyon. A climber of 53 years, Pat’s taken the long end of the rope of life. On a recent afternoon at his MSU office, Pat shared with Outside Bozeman some of what he’s experienced and learned over the years.

To Be a Climber or To Be a Chemist

“When Gayle and I got married it wasn’t a huge sacrifice to balance a career, family, and climbing as I didn’t want to entirely get out of the academic track. I had enough excitement about chemistry and family that I was able to do that. I feel fortunate that I was able to meet people who were devoted climbers, who did a lot of the creative aspects of picking out great objectives and seemed happy to have me along. So I was able to get in on some really notable first ascents without having to do the groundwork. And I’ve always been very enthusiastic about being a professor. I feel as though I’m doing my best work now, in some respects. It’s just been such an important, rewarding part of my life. It will be difficult to turn my back on it and cut myself off of it, so I think retirement will be somewhat gradual.”

High Points in the Vertical World

“With most of the notable climbs that I have done, I’d have to say it was my partner who had the idea to do it. I was a very good facilitator—once someone pointed out a good idea to me, I was very good at making sure it got done. This pattern began with Dan Davis in Seattle while I was in graduate school. He was my partner on two climbs that drew attention: a first winter ascent on the north peak of Mt. Index and the first ascent of the north face of Mt. Robson in the Canadian Rockies. Getting up the north face of Robson was an incredible moment. It was Dan’s idea to go up there. At that time Fred Beckey and Yvon Chouinard and others had made attempts on it, and I didn’t feel like I was in their league. When we went there, it was understood, but never spoken, that the north face would be the objective. I thought that just to get below it, just to get near it, was satisfying for me. It turned out that the north face was the only route on the mountain in shape; we got there at the perfect time.

“Developing routes at Suicide Rock in California was very exciting. Local veteran climbers believed that that particular rock was just too steep to free-climb, that it was an aid area only. However I got on it one day and discovered that it really wasn’t too bad; there were all of these new climbs just waiting to be done. While I was living there 40 new routes went up, and I was involved in 25 of them. I also drafted the first guidebook. All of the routes were bolted on lead; it was low enough angle that you could do that... that’s how steep it wasn't!”

It’s a Family Affair

“My wife, Gayle, was involved in climbing from the beginning. When we were courting she climbed with me, and it was a big part of our bonding experience. It led to a great deal of understanding on her part. My compromise was that I was never gone for more than two weeks at a time, until I went to China for an expedition in 1982 where we were gone for two months. Other than that, I have not been absent too much. My children did become good climbers, but they never had the passion for it that I had. Selfishly speaking, I’m not that unhappy with that! Having to go through the dangers of dodging the bullets when you are first climbing... I would have suffered a good deal if they were out climbing with people who I wasn’t sure they should be climbing with. I believe that not everyone has that desire to climb. It’s hard to define, it’s there or it isn’t.”

Fear

“In China there was an avalanche that came off of a 45-degree snow face that we were planning to climb. It occurred during a squall, we thought we had a safe positioning of our tents; we didn’t expect a lot of accumulation. It turns out we were right; the avalanche only clipped the corner... but we still moved the tent! Another moment was on Emperor Face of Robson with Jim Kanzler. We were on a long traverse to retreat from the attempt and we got to a point where the climbing was too technical and Jim lowered down to the next ledge. It wasn’t clear if that would lead to anything, and we didn’t want to have to rappel straight down as it was warming up and rock was peeling off of the face. The worst part of this incident was when Jim was climbing back up to the ledge he fell, penduluming hard into a wall. Luckily he was protected by his pack and was uninjured. In retrospect, what has stuck in my mind is the almost pathological absence of fear during those incidents. In more general terms, I recognized at some point that easy climbing is what you have to look out for. Partly your attitude gets bad, and secondly it’s often low-angle and loose, and if you fall you are likely to have less gear. I treat easy climbing with almost more respect than a steep part. I feel very wary when I don’t feel that edge of nervousness or anticipation.”

Aging

“I used to dread it and try to imagine what it would be like. I can’t believe I am still climbing to the level I am at this age. In fact when I was 40 my climbing fell off a bit, because I thought that was what was supposed to happen. I noticed that a lot of the well-known climbers dropped off significantly when they got to that age, and I thought it must happen, that it was inevitable. A little while later Bill Dockins and Scott Anderson developed a bouldering area on the Gallatin and made it very convenient and very exciting to go work out; and I found that at that even at age 42 I could improve from week to week. Also at this time my shoulders started to hurt, which I thought really marked the end of climbing for me. But when I started bouldering and climbing more, the pain went away. Not climbing was the cause of both problems, the physical and mental. It wasn’t because of my age. What’s it going to be like the next 10 or 20 years? Who knows. But the last 15 years I’ve taken a different attitude: just don’t have preconceived notions, just do what you want to do.”

Civic Duty

“I’ll be quick to say that I do almost nothing on the board of the Southwest Montana Climbers Coalition (SMCC), but I am honored to be included in it. I would like to give a great deal of credit to Tom Kalakay for initiating the organization, and the good work he has been doing. A key member of the Board is Bill Dockins, who along with wife Kristen Drumheller, have been prodigious in establishing the quantity and quality of rock climbs in the this area. Prior to SMCC's efforts, climbers were a somewhat invisible population. What brought the necessity for an organization like SMCC to a head was emergence of climber’s trails and erosion issues that occurred at the Scorched Earth and Gallatin Tower climbing areas. With the diplomatic efforts of Bill, Tom and other members of SMCC talking with the Forest Service, close cooperation has been established, and access to these areas is no longer threatened.

“Over the years I have been responsible for the formation and operation of the Alpine Rescue Group, one of about 12 specialty groups that collectively comprise Gallatin County Search and Rescue. In the early days before any organized effort, Jack Tackle and/or myself, and anyone else we could round up, were asked by the sheriff to respond to accidents occurring in a climbing environment. Since I had rescue experience in Oregon and Washington, I felt as though I should take the initiative to organize a specialized group to help the sheriff in such situations. My philosophy is that a climber wants to be rescued by active climbers who have years of experience in high-angle alpine climbing. It is fair to say that this group does not exist for the ‘ego trip’ of doing rescue, but rather because it occasionally needs to be done and that they are experienced to do so.”

On Belay

“In a way balancing life between chemistry and climbing has been a continual problem, although, I guess it’s not a problem with a solution—I’ve tried to imagine doing one without the other, but it simply isn’t imaginable. I didn’t feel like I had a choice in the matter, ultimately. There are times that I think it would be really neat to do what I didn’t do when I was younger, to just go climbing for a longer period of time. I will do that, I think. I’m just not quite sure when.”