Slippery Slope

How NOT to climb Granite Peak.

Granite Peak is the most vexing mountain in the state of Montana. There may be mountains in Montana that are more difficult to climb, but the thing about those mountains is that you don’t actually have to climb them. The summit of Granite Peak, on the other hand, is a mandatory stop for any Montanan who claims to be any sort of mountaineer.

The Geography of Granite Peak

At 12,799 feet, Granite Peak is the highest point in the state (and in Park County, for the types who feel the need to bag the highest point in every arbitrary division of God’s earth). This elevation comes in a dismal tenth on the list of state highpoints, behind even Hawaii. But elevation bears little relation to difficulty, and Granite Peak is widely considered the second-most difficult state highpoint to climb, after Mt. McKinley in Alaska (although partisans of Washington’s Mt. Rainier and Wyoming’s Gannett Peak would debate this point).

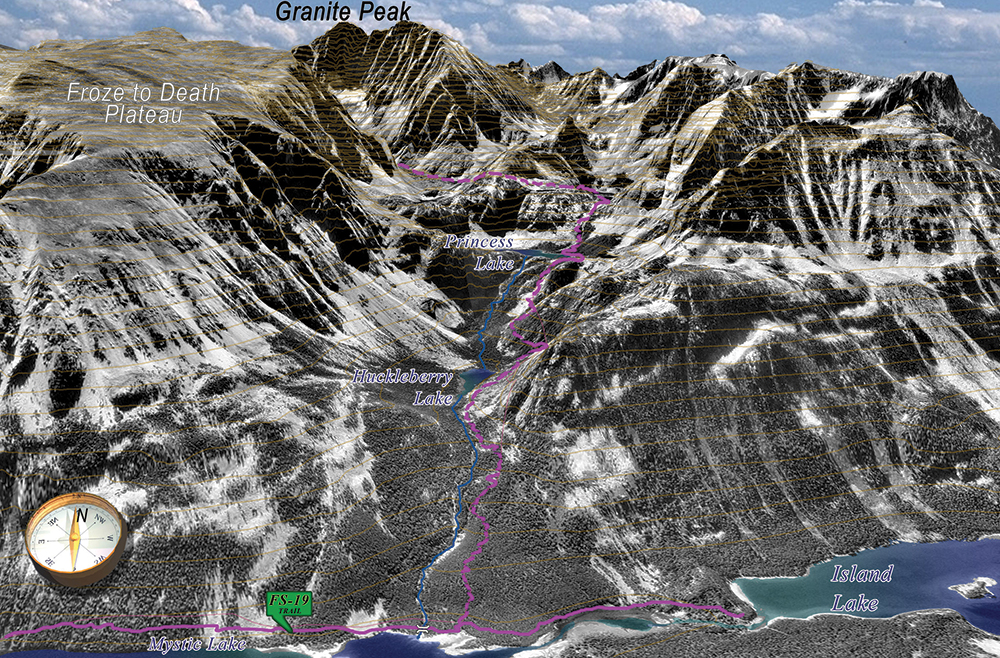

The “easiest” route to the top involves three miles of steady elevation gain along the West Rosebud Creek trail to Mystic lake, followed by three more miles up the 26 “switchbacks from hell” on the Phantom Creek Trail above Mystic Lake. This only gets the climber to the base of the Froze-to-Death Plateau, where several miles of trudging across boulder fields is followed by a steep traverse across the flank of 12,486 feet Tempest Mountain, then followed by a grueling scramble up Granite Peak’s middle boulder skirt, before the real climbing begins a few hundred feet below the summit. All told, it is a 24-mile round trip from the trailhead, encompassing large swaths of every variation of nasty terrain available in the state of Montana.

The less common Huckleberry Creek route.

The less common Huckleberry Creek route.

Directly below the summit cliffs of Granite Peak is the infamous “snow bridge,” a permanent snowfield covering an extremely steep saddle that must be crossed to reach the top. The snow bridge deserves both infamy and scare quotes because it is one of the most dangerous parts of the ascent. Every trip report and guidebook that can be found on the subject of Granite Peak includes the warning that an ice axe and crampons are recommended, along with a roped belay when crossing the snow bridge. It is only a minor obstacle, anywhere from ten to 50 feet across, depending on the time of year. But a slide off of the snow bridge is a slide into a vertical chute with certain disaster the only plausible outcome.

This is where I get to the part about how NOT to climb Granite Peak.

The Climb

My brother Roger and I left the Mystic Lake trailhead on the morning of the last Saturday in August 2005, intending to set up our base camp on the Froze-to-Death Plateau a few miles shy of the summit. We were accompanied by our 74-year-old dad, Dallas Roots, who hiked with us up to Mystic Lake for a sack lunch.

The scene at the trailhead did not bode well for our expedition. A search and rescue operation was being manned by the concerned family members of a hiker who had been missing for several days. We were given a flier at the trailhead with the missing hiker’s vital information, and we promised to keep an eye out.

At Mystic Lake, Roger and I parted ways with my dad, who turned around and began his journey back to the trailhead. Unbeknownst to us, he shortly encountered a man in his 50s who was hiking up the trail with his son. As my dad approached the pair, the older man fell into the throes of a heart attack. My dad did everything he could to help, from performing CPR to shouting at the top of his lungs. But the man died right there on the trail.

Oblivious to the tragedy unfolding below, Roger and I set up camp at a nondescript point on the plateau above Mystic Lake. On Sunday morning we stowed our camping gear and made our way to the peak, realizing that a late start had put us behind schedule. We reached the snow bridge at around 1:30 pm, with the summit in sight. We brought rope and rappelling gear for the climb down a couple of the trickier cliffs above the snow bridge. And I put on my rock climbing helmet in case my brother dropped rocks on me.

The snow bridge was steep and looked as dangerous as advertised. But it was only seven or so steps across, and we didn’t think twice about simply crossing it, giving no thought to roping up. Yes, it was a long way down if one of us fell, but that’s the way everything is up there. Worrying too much about falling can have the detrimental effect of making a fall more likely.

The climb to the summit encompasses several chutes with a near-vertical pitch. These were not easy, to say the least, but we made it up and celebrated triumph on top of the mountain at 3 pm.

Standing on top of Montana.

Standing on top of Montana.

The Fall

We didn’t stay long. We realized that we had an unfair advantage over innumerable others who had attempted to reach this same point. Granite Peak and the Beartooths are known for wildly unpredictable weather, and thunderstorms hit almost every afternoon. Summiting the mountain during the afternoon is usually a terrible idea.

We rappelled two of the trickier chutes near the top, and downclimbed the rest. By 4 or 4:30, we reached the summit end of the snow bridge. A bit earlier I had even joked about “roping up” across the snow bridge, a ludicrous idea given what a minor obstacle it was.

Roger retraced the seven steps we had kicked into the snow on the way up and was across in a matter of seconds. I went right after. The steps we had followed were now sloping downward and were a little bit more awkward than they had been on the way up. But it was only seven steps, and I never hesitated.

On the last step of real danger on Granite Peak, my front foot slipped. A slip is always a panicky moment, but for the briefest of seconds I thought I would be fine. I was so close to being across the snow that I could actually reach the rocks on the other side with my right hand as I slid onto my chest. Unfortunately, the “rocks” my hand grabbed were nothing but loose gravel that slipped through my fingertips.

I slid. And slid. And picked up speed.

Mountaineers have debated the best way to arrest a calamitous fall. Regardless of the method, stopping your own descent is generally better than having it stopped for you at the bottom. In researching this issue, I found a website describing various self-arrest techniques to use depending on the equipment you have. The site concluded that the only good that comes from a self-arrest with no equipment is the lesson learned about why such equipment is necessary.

The snowfield under the snow bridge descended about a 100 feet before the near-vertical slope continued through a field of rough boulders. I turned over onto my back as I slid down the snow and saw a large boulder that I intended to plant my feet on to slow my descent. I knew it was going to hurt, but in my position everything was going to hurt.

I don’t know if I hit the rock with my feet or not. I went into a tumble at the boulders and rolled over and over, bouncing and scraping my way down. The boulders ran into another snowfield that terminated at a steep scree slope that kept going down and down, several hundred feet past my view.

I kept tumbling, flailing my arms, screaming in pain and terror. And embarrassment. People die at this spot. And here I was, dying at this spot. Every tumble was agony, but I kept waiting for the one that was really going to hurt. The one that would break my bones or knock me unconscious. My situation all but guaranteed that it was coming.

A long way down.

A long way down.

But it didn’t. In the scree field I finally came to a stop. I’d like to think that I’d fallen correctly, that I’d put in just enough effort in flailing and scraping for life that I managed to stop before I hurt myself worse. But I really can’t take that kind of credit. An uncontrolled fall is so random and arbitrary that the avoidance of the coup’de grace is in somebody else’s hands.

If anything helped my cause, it was the warm weather that had reduced the amount of snow covering the boulders and scree. On almost any other weekend the snow chute would have spit me out onto the boulders much farther down the slope, and at a much greater velocity, making stopping much more difficult.

The Aftermath

My arms and legs were scraped up and bloody. If nothing else, I know I scraped and clawed at that mountain as much as a man in my position possibly could have. I stopped in a perfect position, with my back on the mountain and my feet toward the bottom. I sat up (which somebody with possibly serious injuries shouldn’t do) and panted for what seemed like ten minutes trying to catch my breath. Amazingly enough, nothing seemed broken. I had a bad gouge in my right wrist, but nothing seemed out of place otherwise.

My brother scrambled down as fast as he could once he realized that I was not only alive but conscious. When he had seen me start tumbling he said that he knew I was a goner and almost took off running for help. He bandaged my wrist up and we both sat in disbelief as a cursory examination turned up no other injuries. Both he and I knew the tricks that trauma can play on the mind, and were not convinced that my lack of serious pain meant a lack of serious injury.

My helmet had probably saved my life. The new innocuous dings and scratches on it now could have very easily been less innocuous fractures in my skull. My jeans were torn to shreds, and I had bruises and scrapes up and down my body. But I was alive, and I was going to walk out of there under my own power. This was vital, because every mountaineer knows how problematic a mountain rescue can be. A compound fracture, perfectly treatable in a car accident, can be a fatal injury when left untreated for the interminable hours before help can arrive. Even a minor ankle injury could mean death if it meant that walking was no longer possible.

Getting Home

But the 12-13 miles back to the trailhead were not easy coming in, and were not going to be any easier going out. Our base camp was in a boulder field identical to every other boulder field on the plateau. We had dutifully recorded its location with my GPS receiver but to our dismay, the GPS had been in my pants pocket for my slide down several feet of mountainside and no longer responded.

In addition to providing the worst sort of terror, my fall also killed a lot of time. With darkness rapidly approaching, we had no hope of turning up our tent and warm sleeping bags. We bivouacked under some uncomfortable boulders for the night, covered by a rain poncho and a space blanket. Roger and I alternated between shivering uncontrollably and having our extremities go numb as a result of awkwardly trying to “lie down” on a pile of rocks.

At daybreak, we gathered our bearings and spotted our tent. And we slowly made our way back down to the trailhead. Once in my truck, we made a single pit stop at a gas station for Dr. Pepper and ice cream sandwiches before heading to the emergency room. There I spent several hours having chunks of rock gingerly extricated from the gouge in my wrist.

In the aftermath of that weekend, one man died on the trail, one missing hiker was found dead at the bottom of a crevasse, and one jackass too cheap to buy an ice axe was extremely lucky to not have joined them.