True Tales: Play by the Rules

Committing ice climbing’s cardinal sin.

“Some rules are made to be broken.” That’s a thing people say, right? Mostly badass people, I imagine—dudes who talk with a slow rasp and smoke cigarettes and look perpetually toward the horizon, as if searching for the next rule they might break in order to sleep with girls impress their coolness upon the world. I wouldn’t know. I’m afraid smoking would give me cancer and ruin my complexion.

Of course, there is an important inverse to that rule, which goes something like “Some rules will break you when broken.” Examples of this include pointing a gun at police, taking selfies with bison, and attempting the cinnamon challenge. In ice climbing, the cardinal rule is “Leaders shall not fall”—and I’m about to tell you how I learned that lesson well, years ago.

It was a classic full-on early winter day in Hyalite. Snowing, blowing, and frigid. Perfect weather for climbing ice, which tells you just how miserable the sport really is. My partner and I were on the third pitch of the classic Dribbles, and after two pitches of easy, forgiving ice, confidence was high.

I had new ice tools and was, for the first time that season, feeling strong. On this day, the pitch was looking somewhat thin, with water flowing visibly through several portals in the dead-vertical curtains of ice. But it was in great shape.

I was enjoying effortless single-swing sticks that resonated with the dull “thump” of confidence inspiring ice density. I placed only a few screws, mostly as a formality, and used whatever size happened to be racked at the front of my harness. There was no way I was going to fall, I thought. As a result, I was moving fast—faster than normal—and found myself far above my last protection, just below the crux, where a bulge pushed the ice angle steeper for 8-10 feet before easing back. My last screw—a stubby, by chance, just 10 cm long—was at least 15 feet below. But the top of the bulge was in sight. Above that, the climbing would become easier. I decided to push through and just get there—I was feeling strong and the ice was perfect. And then, suddenly, it wasn’t.

In the distance of two moves, the ice became brittle and fractured. My single-swing sticks turned into a hackfest, and as I swung (and swung, and swung), I could feel my strength waning. I started to consider how far I was above my protection: over 20 feet. So I sank one tool into the brittle mess, and clipped into the spike with a draw. I placed a screw, hung a draw from it, and tried to make the clip—but the twin ropes were wet, heavy, and dragging, and wouldn’t quite reach. I pulled hard, then felt my feet shift.

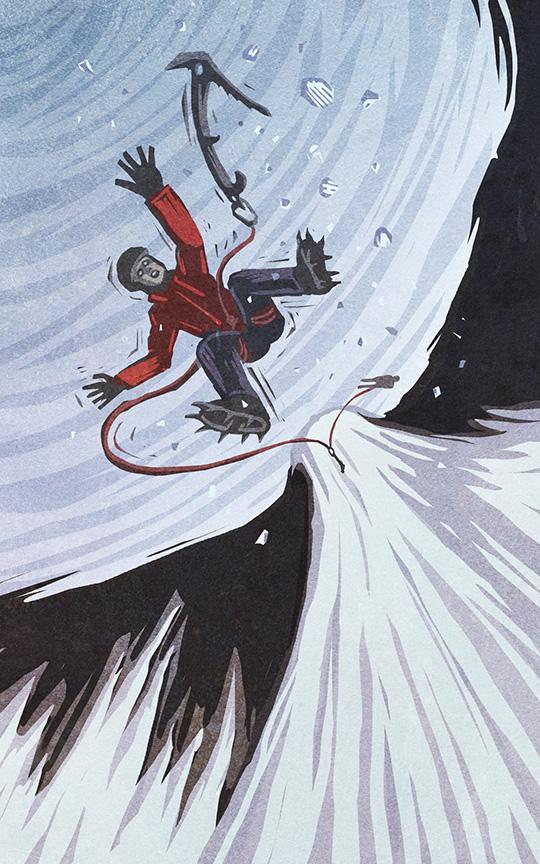

Both of my crampons blew out at the same time. The tool to which I had clipped the rope promptly popped, and I was airborne. I apparently kicked my feet out and covered my face (I don’t remember) just in time take a bulge hard on my hip and bounce out toward 250 feet of empty space. My new ice tool, still clipped to the rope, swung wildly around my head like a dagger. I fell long enough to wonder whether I was going to stop. Then as the rope stretched, I swung back into the ice and slammed hard on my side before coming to a rest between 50 and 60 feet feet lower than I began. Lucky doesn’t begin to describe my fortunes.

After a hasty lower and cursing a streak as blue as the ice, my rather unimpressed partner assessed me for injuries. Somehow, I was just bruised. It is only by sheer providence that I don’t now resemble a pirate, with a peg leg and eye patch—accessories one might expect to incur by falling down a vertical icefall wearing finely-honed, ice-catching daggers on every appendage.

Another cliché I quite enjoy is, “It’s better to be lucky than smart.” Hallelujah. But in all seriousness, this day could have ended in the worst way. In falls like this one, crampons often lead to severe ankle and lower leg injures, punctures, and lacerations. I shudder to consider the potential consequences of the ice tool orbiting my head. The impacts of hitting two bulges produced enormous green and black bruises, but could have broken any number of bones. And had that stubby screw not held, I would have probably hit the deck, with dire consequences. It was a harsh wake-up call, and though this accident occurred years ago, I think of it every time I tie into a rope, and am grateful.

“Ice leaders don’t fall.” Trust me, this is one rule that wasn’t made to be broken.