An Open Book

Local climbing legend Ron Brunckhorst.

Enigmatic climber, route developer, guidebook author, local legend: for more than 40 years, Ron Brunckhorst has been quietly exploring Montana’s vertical realm of rock and ice. In that time, he’s built a reputation for putting up routes that prioritize adventure and solitude (often at the expense of rock quality), and publishing guidebooks that, with notoriously few specifics and understated advice, project his own Montana ethos of exploration. Follow any description in one of his five books, and you may just find yourself two pitches up a chossy wall, wondering aloud which ambiguous left-trending crack system is the actual route. This, contrary to how you may feel about your predicament, is precisely where Ron wants you: on the sharp end, a little scared. “The climbing itself is what inspires me to write these books,” he explains. “I love to do new routes, and once they’re done, I also love sharing them with people.”

Brunckhorst and I met last spring at Sacajawea Park in Livingston. As we chatted, the middle-school track team ran past and one of them shouted, “Hey Mr. B, bet you can’t do a one-finger pull-up.” He turned to me with a smile and adamantly maintained that he could. He just worried that if he proved it, the kids would get hurt trying it themselves.

He’s 55 years old, unassuming, with a shock of boyish hair framing his angular face. With a cheap Casio watch riding above his wrist and old New Balance runners steadily drumming the ground, his appearance falls somewhere between golf caddy and substitute teacher—the latter of which happens to be his job. But despite Ron’s humble mien and civil vocation, his resume is filled with routes that annually challenge and frighten Montana climbers of all stripes. Since his teenage years, Ron has made it his mission to discover, establish, and record new climbing routes across southwest Montana.

Native Son

Brunckhorst grew up an hour and a half northeast of Bozeman, in White Sulphur Springs, where he and his brother Gerald spent their childhood hemmed in by the Little Belt, Big Belt, and Castle mountains—the latter an old, low range of craggy hills visible from White Sulphur’s historic main street, where the Brunckhorst brothers first taught themselves to climb.

“I remember going on a backpacking trip from Cooke City to Red Lodge

with my family, and I’d bag a peak every day along the way.

My parents were never afraid to let me go off by myself.”

Rock climbing was a fringe activity in the 1970s, and they turned to a beat-up library book for tutelage. “I remember looking at this book in the White Sulphur library. It was an old-school how-to-climb book,” Ron recalls. Probably an early Royal Robbins tome, its discolored black and white pages were stirring. “If I wasn’t reading that book, I was thinking about it, or drawing it. I loved it.”

Ron’s parents raised their children free-range. “This sounds terrible now, but my folks would drop Gerald and me off at Grasshopper Campground in the Castles for the weekend, and we’d stay up there scrambling around,” Ron says. “We used to go climbing with this rope that wasn’t much better than a clothesline, and five or six chocks,” Ron remembers. “It’s all limestone where we were trying to climb, so we had a really steep learning curve.”

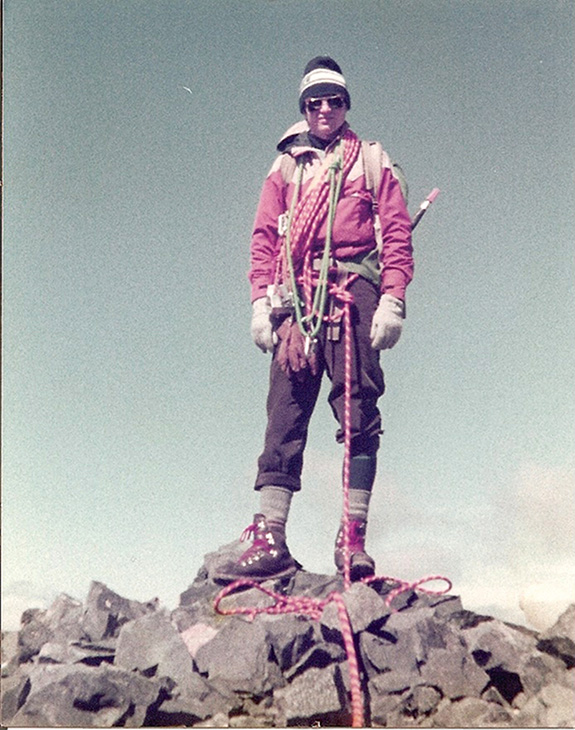

Ron on the summit of Iddings Peak,

10,936 ft., Crazy Mtns., early 1980s

Ron’s and Gerald’s parents didn’t climb, but being outside was a family tradition. “We were always going hiking as a family, so I was exposed to the outdoors from a young age,” Ron says. “I remember going on a backpacking trip from Cooke City to Red Lodge with my family, and I’d bag a peak every day along the way. My parents were never afraid to let me go off by myself.” Just five years ago, Ron dug his mom out of an avalanche in the Bridgers that buried her up to her waist.

When Ron turned 16, he and Gerald packed up the family’s spare car and headed for Grand Teton National Park to climb the park’s namesake peak. Near the upper saddle between the Grand and Middle Tetons, where Exum Mountain Guides operates a hut, the boys ran into a guide named Jim Kanzler. Jim was already a Northern Rockies legend in his own right. “He was concerned and kept asking us where our parents were,” Ron says with a chuckle. “He told us to follow him, so we ended up tailing up the entire Owen-Spalding route.”

After Ron graduated from high school in 1982, he moved to Dillon to earn a B.S. in natural heritage at Western Montana College. During his freshman year, Ron met a young mathematics professor named Craig Zaspel, who would go on to become one of Ron’s most consistent climbing partners. Ron relocated to Bozeman in 1986 after graduation, and started his guide service, Reach Your Peak, five years later.

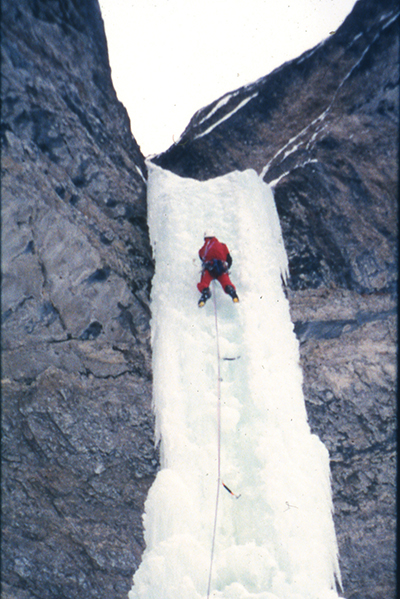

600 feet of ice (IV, WI 5), south of the summit,

Barronette Peak, Yellowstone Park, 1997

As Ron worked to establish himself as a reputable guide, he and Zaspel, alongside a rotating cast of climbers like Dave Vaughn, dedicated themselves to developing summer and winter routes around southwest and central Montana. “Ron is really friendly, and he’s from central Montana, so the ranchers saw him as a local,” Zaspel remembers. “This was extremely helpful for us in securing access to new routes.”

Ron and company’s most prolific years were dedicated to fast and light alpine-style ascents all over southwest Montana, including the North Ridge of Tweedy Mountain in the Pioneer Range and north-face routes on Mount Cowen in the Absarokas and Mount Wood in the Beartooths. Ron’s alpine routes, particularly those on the notoriously loose rock of the Crazies, are responsible for garnering him a reputation as a climber dedicated to fringe adventures.

“People were always saying to me, ‘Somebody oughta write this stuff down.’

So I did.”

But Ron is reluctant to acquiesce to this renown. Critically speaking, some of Ron’s climbs are entirely rotten rock. However, seen through his eyes, they are good enough, and certainly worthy venues for some exploration. “Ninety-five percent of the rock may be rotten in some of these places, but five percent of it is good, and so good, and there’s just so much of it,” he says. By Ron’s calculus, five percent is a significant chunk of climbing in the state of Montana, and it’s there for the taking. “Sometimes I do go a long way to do a route,” he admits, “but I’ve also put in plenty of climbs that are close. Some of the crags I’m working on in the Castles are close, and have some of the best routes I’ve ever done.”

In the ’90s, Ron and his cohort refocused on crag development over alpine firsts. During this period, Ron filled out entire under-the-radar spots with bolted and mixed lines that retained a recognizably Brunckhorstian aesthetic. Areas like Indian Creek near Townsend and Bear Canyon’s limestone outcrops were some of his lasting ’90s additions to the Montana scene that remain quiet and a little dirty to this day.

As Zaspel explains, “In the 1990s there was a lot of limestone development in the obvious areas like Bozeman Pass, so we went to the overlooked areas like Bear Canyon.” Eventually, Ron turned his focus back to developing climbs in the Castle Mountains, most of which are documented in his most recent, and most widely used, book, The Big Empty.

Open Books

Since 1991 Ron has penned five self-published guidebooks to some of Montana’s quietest and least-accessed summer and winter climbing areas, many of which he helped develop. In that time, Montana climbers have been especially lax on recording route information. “People were always saying to me, ‘Somebody oughta write this stuff down,’” Ron remembers. So he did. But Brunckhorst admits that he was never a strong writer. “I haven’t climbed Everest, but writing my first two books was just as hard for me,” he says. “I used to literally beat my head against the wall while trying to write.”

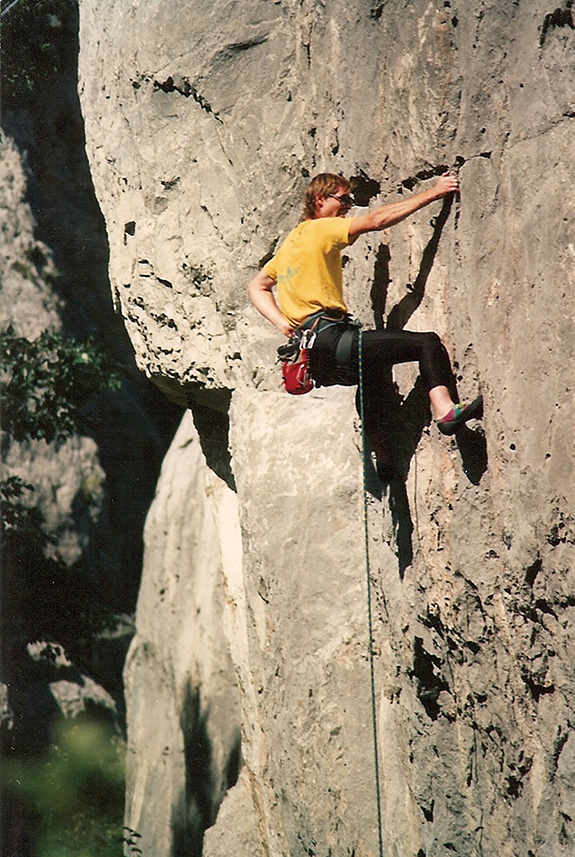

First ascent of War Party (5.11c) at Indian Creek, May 1992

His first and most well-researched book, the first edition to the classic Big Sky Ice, came out in 1991, and in its current edition is arguably the most encyclopedic resource on Montana’s winter climbing. Brunckhorst made that first edition “the old-school way,” by cutting out printed pages of text and photos with an X-ACTO knife, then gluing them onto a template before scanning the whole mess into a final document. Almost all of the topographic maps in his books are hand-drawn, and even his more polished volumes aren’t without grammar and spelling errors.

Although his books lack glossy gatefolds, detailed route information, and precise topos, they are timeless resources filled with charmingly concise information. According to Ron, this is all part of the plan: create guidebooks that don’t spoil the adventure, but that don’t sandbag it, either.

Most people who have used a copy of Ron’s books describe the climbs in similar (sometimes sarcastic) terms: scary, dirty, loose, memorable, epic. In Brunckhorst’s worldview, it’s better to under-rate than over-rate a climb, and “go left” means “go left.” No fluff, just relevant beta. He sees his books as passports to authentic mountain experiences.

“I’m more into telling people how to get to a climb, and not so much into sharing the blow-by-blow details of the actual climb itself,” Ron explains. His route descriptions can be sporting at best. “I want to leave some adventure to the climbs,” he says. “At the same time, I don’t want people to have mis-adventures.”

Despite his DIY publishing ethic, Ron is accepting of platforms like MountainProject.com, but does admit to feeling threatened by them on occasion. He makes an allusion to a friend who posted a route they had worked on together before Ron could print it in his guidebook. “That felt like a bit of a jab.”

Climbing On

These days, Ron’s life runs at a slower pace, and he finds comfort in the relatively secure career of substitute teaching. Typing in his guide business’s URL prompts a 404 Error. He’s a happily married man, who ultimately grew tired of the guide’s life. “People were flakey, and I didn’t want to deal with it anymore,” he says quietly, as if to not offend them. He still feels like he’s growing in his climbing, but admits that his out-and-out climbing fitness is not at its peak. But, much like an aging tennis player, his technique and mental acuity have been honed over the years.

His climbing partners have changed, too. His brother Gerald has kidney failure, and has been worsening since the ’90s. Just before his diagnosis, the two completed the first ascent of The Silver Cord in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone during a cold May in 1991. The Silver Cord represented something of a swan song for the brothers’ partnership. It’s a stunning ice route that sees only a handful of ascents annually. A couple of years ago, two people died on the route when the whole thing came unglued.

First ascent of the 230-foot Spicy Plum (WI 5),

North Fork of Deep Creek, Absaroka Range,

December 31, 2005

As older climbers often do, Ron makes multiple allusions to “barely making it,” or generally “getting away” with climbs. His sense of mortality is evident. But despite his normalizing lifestyle, writing new books and opening new routes is still on his mind. Almost every Montana climbing guidebook, including more recent bouldering books, is in need of updating. While more mainstream guidebooks are released at a glacial pace, Ron has always disseminated information his own way: self-published at home and by hand.

And he keeps putting up new routes—although, with a nod to the increased popularity of rock climbing, Ron now prefers to establish routes that are bolted safely. “If I’m going to take the time to clean these routes, I’m going to make sure they’re safe,” he says. “If it’s a 5.8 route, I want it to be so that a 5.8 leader gets sucked from bolt to bolt, rather than needing to be a 5.10 climber in order to do it because of a run-out.”

Still, at the end of the day, Ron isn’t apologetic for the sometimes-suspect nature of his famous original routes. They were products of the times. “There’s still a place for spicy routes,” Ron argues. “It’s nice to have climbs that people can challenge themselves on in that way if they’re feeling up to it.”

Brunckhorst Bibliography

The following books can be purchased at Vargo’s, Country Bookshelf, and Spire.

Big Sky Ice, third edition

The author himself considers Big Sky Ice to be his best work. To be sure, it’s the most thoroughly researched and usable of his three commonly available guidebooks. Ron’s abiding passion for winter climbing abounds herein, and as a result, Big Sky Ice is arguably the authoritative volume on ice climbing in a state notorious for withholding beta.

The Big Empty, first edition

This is Brunckhorst’s love letter to central Montana, where he grew up. Aside from his early Indian Creek (MT) guidebook, The Big Empty is his only guidebook dedicated to cragging and is therefore very popular. The Big Empty looks at the limestone crags, towers, and outcroppings that run from Canyon Ferry, through the Little Belts, Big Belts, and the Castle Mountains.

Select Alpine Climbs to Montana, second edition

This book is Ron’s best gift to the adventurous climber, and a bookshelf essential for any true Montana alpinist. Even if you only occasionally dip into this book for your weekend plans, it’s worth keeping around. Select Climbs is dedicated to summer and winter alpine routes scattered across the state, the majority of which are difficult to reach, not oft-repeated, and technically demanding.