Washing Off the Dirt

Gravel biking, misplaced IVs & hard lessons.

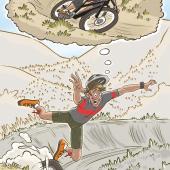

The light blinded me as I pushed open the door of the aid-station porta-potty. I stumbled out, my legs simply tree trunks at this point. To reach my bike, I had to sneak past the medic—the one who had warned me that should I retch, there would be no hope of finishing the 100-mile race I’d foolishly signed up for.

In my mind, I became a cat—skittering around the aid station feeling invisible, with the intent of reaching my bike and taking us both to the finish line. In reality, I was a heavily-dehydrated human with bloodshot eyes and a dirt-, sweat-, and vomit-encrusted face, slowly stumbling through the area.

The trek to my bike was cut short. The medic stopped me midway, towering over my short stature, something my Napoleon complex wouldn’t normally let happen. “You need an IV,” he said. I’d been defeated.

At 12, my dad declared that I needed to find a sport. Heavily influenced by my dislike of team sports, I decided I was going to join him in a silly, spandex-filled activity that makes your fear of moving cars minimal and your calves massive. I apologize if this isn’t specific enough—to be more clear, I began road biking. There would be races here and there, but more often than not, just simple morning rides with my dad and the small bouquet of individuals that he had hand-picked, knowing that they could act as archetypes on which to base my own developing personality.

Thinking that 100 miles on gravel would be no different than on a road, I was much too quick to sign up for quite possibly the worst gravel race you can do as your first.

Bless my dad and his patience—I cried a lot. I would cry climbing, as my dad casually pedaled next to me, struggling to avoid saying the wrong thing. I would cry at the top of hills, knowing that there were more to climb. I would cry when my dad yelled to me, “Why do we climb hills?” and proceed to scream, “To go down them!” as he’d bomb down the road, leaving me behind to grip my brakes the whole way.

It didn’t take me long to realize there wasn’t much of a “career” for me when it came to cycling. I’m a slow climber, and my endurance is mediocre. I have the sprinting capabilities of a criterium racer, but the competitive drive of a turtle. Eventually, I stopped pretending to be competitive and tried other types of biking that seemed a bit more “cool” for a woman entering her 20s.

Most recently, to follow suit of the other Lael Wilcox admirers and wannabes, I sold my road bike in exchange for a gravel bike. Thinking that 100 miles on gravel would be no different than on a road, I was much too quick to sign up for quite possibly the worst gravel race you can do as your first.

I found myself sitting in the back of a very nice man’s weather-chasing van with a little bit of dried vomit stuck to my face and track marks along my arms from a poorly inserted IV.

“How you doin’ back there?” He asked out of what I assumed to be either kindness or a hope to end the weighted silence of failure. My mouth, usually all too ready to speak up, seemed to be at a loss. I gave him a thumbs up.

The days of my dad being faster than me are gone, but I hold on for dear life to the memories of us spending hours together every Sunday morning.

“The fridge back there is stocked, it’s got soda and bubbly water,” he said. I nodded and proceeded to crawl to the fridge, a cherry water for me and a lime for him. I cracked the can before handing it to him. We drove in silence until we reached the finish line where Rebecca Rusch beamed as she handed awards to the finishers.

“Thank you,” was all I said when I left him, but he and I both knew the weight of the words were more than they seemed.

Humiliation pumped through my veins that day. In the van, a call from my dad came through. I rejected it. I didn’t call him that night as I shoved a pound of Oreos in my mouth. I didn’t call him on the ride home, the loud hum of my jalopy truck muting my avoidance. I didn’t call when I arrived home and watched layers of sweat and dirt swirl into the shower drain.

It took me two days to call him back. His reaction was only endearing—there were laughs, “yikes,” and more importantly, extraordinarily kind words of support. He emphasized that things are hard sometimes, but the importance of it is that we at least try. And that while we try, we enjoy it.

I don’t bike because I want to win. I bike because I want to bike.

I bike because sometimes I really don’t like running. I bike because sometimes it feels really good to sit on a driveway with a close friend and laugh at the pain that we just put ourselves through while we knock back mini-Cokes to restore our depleted sugar levels. I bike because I relish introducing people to the sport when they’re too intimidated to try it themselves. I bike because I tattooed a bike chain on my arm and it would look weird if I didn’t bike. But again, out of all of these reasons, I bike because I want to.

The days of my dad being faster than me are gone, but I hold on for dear life to the memories of us spending hours together every Sunday morning—riding bikes, drinking coffee, arguing, laughing. Maybe I’ll go back and finish that race, maybe I won’t. I’m just here for the good time, really.